As has been shown on previous charts, William Wilkes, the younger, married Elizabeth Haynes or Haines, presumably in Tewkesbury, 15th March 1846, both being but nineteen, she a few months the older of the two.

Prior to this young couple's marriage, in fact when they were ten to eleven years of age, an event of great future consequence was commenced, which was not only to affect the Wilkes and Haines families, but so far-reaching that the whole of the country was to be affected. England was never to be the same, for thousands upon thousands of British families were to become literally uprooted. The whole of the story is far too long to relate in this little family history, but a brief account will be reviewed, for it had great impact on our ancestors of a few generations back

It all started in America, where a religious revival was being held in the western frontier portion of the state of New York. A young boy by the name of Joseph Smith had anticipated joining one of the several optional churches, but had difficulty selecting one most suitable to his fancy. He had been a studious boy, and from the scriptures he had read and pondered over the church of Jesus Christ that the New Testament described. He had become convinced that he should join one of them, and several ministers were pressuring him. The fact that the ministers taught differently as to what the essentials were in order to reach heaven, the young man postponed making a final decision, and yet he felt he should not delay too long.

As he was reading and pondering a scripture on one occasion, he paused. He pondered and read it again. He could not erase it from his mind, and he re-read and pondered over its meaning. It said, "If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God." (James 1:5) He had a problem. What should he do? He said to himself that surely, he was lacking wisdom. There was no question in his mind, but that one of the churches had to be the church for him, but which one?

That this scripture might provide the answer for him, became his resolve, and so, after a time of concern, he made the attempt. This effort did provide the solution he had been wishing for, but it was far different than he had expected, far different than he had ever dreamed. He had found his way into the silence of a shady grove of trees, and knelt. As he proceeded with his prayer, to his great surprise, he was seized by an evil force, which for a few seconds, he thought was going to destroy him. As he felt he was about to be overcome, a light from heaven appeared before him, and two living personages descended just above him, and the evil force left.

One of the personages spoke his name, and Joseph recognized that it was he who was being addressed. The one introduced the other by saying, "This is my beloved Son, hear Him!"

Within the moment, Joseph knew more about God than all his tutoring ministers combined, for he knew that the Father and the Son were beings in the form of men. This was so different than what Joseph had been taught, that he was quite amazed. When he was assured that he was with friends, and when he had gained his composure, Joseph remembered his purpose in coming to pray. He asked his question, which of the churches should he join?

To his great amazement, he was told to join none of them, for they were all wrong, but if he would remain faithful, the day would come when the true church of Jesus Christ would be returned to the earth through him. This was, indeed, sobering to him, but he became greatly relieved. His simple prayer had been answered.

The story of the complete restoration is available to any ready, but it eventually became a reality. All of this happened in America. Young William Wilkes, over in Tewkesbury, England, as also young Elizabeth Haines, were but four years of age when on the 6th day of April 1830, the restored Church was officially organized in the state of New York. At the moment, neither England, nor even the rest of the world, realized the importance of that great event.

It was not for another seven years that England would have an official delegation come to its shores from this newly formed church. By that time, William and Elizabeth were between eleven and twelve years of age, and undoubtedly, they had not been made aware of the arrival of those Mormon missionaries. By revelation from God, Joseph Smith and his co-workers had received a new commission - just as the ancient apostles had in their day - which directed them to take the newly restored gospel to all the world. England was to become the first country across the water from North America, to become the recipient of such a commission. As a result of a special call to an apostle of the new church, Heber C. Kimball, with three other companions, two of whom were also apostles, left Kirtland, Ohio on June 13th 1837. They were to meet three additional missionaries from Canada, in New York City, who had also been assigned to join the official party on its way to England. It was actually ten days later, that the party booked passage on the sailing vessel, the Garrick, but it was not until July 1st that the nine hundred ton vessel left the harbor.

Twenty days later, at daybreak, the vessel was anchored, and the little party of Mormon missionaries set foot on British soil to start a religious movement in England, which has never had its equal. At the time, very few in all England had ever so much as heard of the Restoration of the Gospel, the message of which was to be imparted to the millions of people of that land. Actually, the newly organized church was seven years old. Very little proselytizing had been done, even in America, excepting rather locally and into Canada, and a little into the western frontier to the American Indians. England became the first foreign country.

One really has to read early Church history to get a glance of this missionary phenomenon, to be able to appreciate the fact that the Lord had sprinkled the blood of Joseph, particularly Ephraim, into the British Isles over the centuries. There resulted unusual success during the first weeks and even months, until Satan's forces, mainly through ministers, found their flocks were being taken from them. Their early courtesies to the Mormon missionaries were to be turned quickly into hostilities, which soon became almost venomous. Regardless of the period of time, the Lord's work meets persecution, and this experience in England was no exception, but despite it, the progress was not stopped. The Lord's Church was to make headway, and it did, even though, seemingly, all hell had broken loose.

No attempt will be made here to follow this early missionary story in the land of our ancestry, excepting to bring to attention a well-known and interesting episode as it may have affected our family.

Three years went by, and the original missionaries to England returned to Kirtland, where the Church was in serious trouble brought on by the 1837 financial depression. Because of bitterness brought on by the financial losses of many of the members due to the Kirtland banks having been forced to close, the Prophet Joseph, although innocent, was, due to his position, connected to the banking business, and so, received the brunt of the criticism.

Excommunication and apostasy was literally destroying the Church in Kirtland, and how timely it was, that the overall membership had been strengthened by the new converts in far off England. The Prophet saw the dire need of this newly-found membership in England, and he was directed, in the face of the calamity at home, to strengthen the missionary force in England. Upon inquiry of the Lord, he was directed to send several of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles to that fruitful field. It was during this period of time -- 1840 and shortly thereafter -- that there were more members of the Church in England than in all the rest of the world combined.

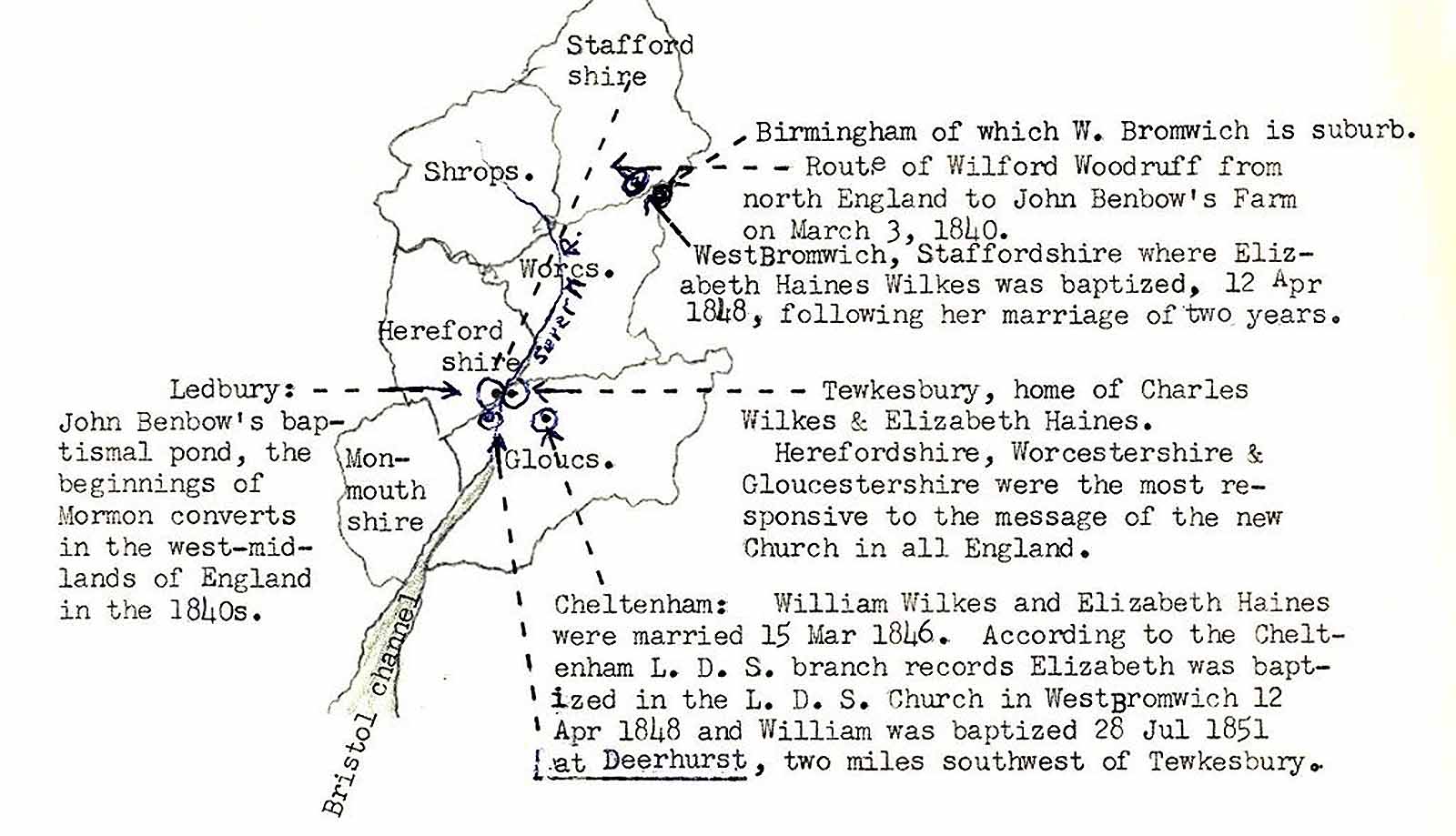

With this group of apostles, was Wilford Woodruff, who after having been assigned to labor in the midlands of England, was impressed to inquire of the Lord of his oncoming plans. The following is a quotation relative to the matter, taken from Cowley's "Life of Wilford Woodruff", p, 116.

"In the morning I went in secret before the Lord, and asked Him what was His will concerning me. The answer I received was that I should go to the south; for the Lord had a great work for me to perform there, as many souls were waiting for His word. On the 3rd of March, 1840, in fulfillment of the directions given me, I took the coach and rode to Wolverhampton, twenty-six miles, spending the night there. On the morning of the 4th, I again took coach, and rode through Dudley, Stourbridge, Stourport, and Worcester, then walked a number of miles to Mr. John Benbow's Hill Farm, Castle Frome, Ledbury, Herefordshire. This was a farming country in the south of England, a region where no Elder of the Latter-day Saints had visited."

As one can readily determine from the map, Ledbury is just a very few miles out of Worcestershire into Herefordshire and is not over ten miles north and west of Tewkesbury, a town about twice the size of Ledbury, and nearby was Mr. John Benbow's farm. Mr. Benbow was a well-to-do retired farmer and had much influence in his neighborhood.

The reader should not fail to review this account of President Woodruff and Mr. Benbow and their success story, for within the next six months, approximately 1800 baptisms were performed. Probably never in the history of the Church have so few accomplished so much. The entire area was astir, and with Tewkesbury being in the center of this activity - only ten miles from Mr. Benbow's baptismal pond - there seems little question but that the families of William Wilkes and Elizabeth Haines would have had an unusual conversation topic around their respective kitchen tables at meal time. These two young people would have been thirteen years of age at the time - old enough to have been paying attention to the conversation.

We become amazed from the above notes surrounding the small map of five or six of the western midland counties, to see that wife, Elizabeth's baptism took place in West Bromwich, for this sizable town is, at least, fifty miles from Tewkesbury. While the Wilkes name is not as common as many names, yet there are any number of Wilkes names throughout the midlands of England and probably elsewhere. Having resided in Warwickshire, the county directly to the east and half way surrounded by Gloucestershire, Worcestershire and Staffordshire, the very shires we presently are involved with, the writer knows from personal experience that there are many families with the name in the roundabout area.

At first, the thought that an Elizabeth Wilkes was baptized a Mormon in West Bromwich, was probably that there was another Elizabeth Wilkes belonging to another family. This was not to be the case, for in reality, the fact that her baptism occurred in West Bromwich is so stated in the Cheltenham branch records.

For the interest of the reader, every Cheltenham branch entry pertaining to the Wilkes and Haines' lines will here be copied:

"Ann Wilkes, d. of James and Lucy. Born 3 June 1825 at Ripeford, Hereford. Baptized 20 Apr 1844 by Henry Webb. Confirmed 20 Apr 1844. Emigrated 9 Apr 1851. (The folk of this entry are unknown to us, however, they have the name, Wilks, but note it is not spelled as our Wilkes. This may mean nothing, for it could have been the clerk's error. There are families in the area using either of the spellings. Not that this young lady was born in Herefordshire and was baptized in 1844. She would then have been a young lady of eighteen years of age - not nineteen until June, and this was April.

"Hannah Wilkes : (The name only appears. The reader will be aware that our William Wilkes, the younger, had a sister just two years older than he, named Hannah. The entry was started with her name only and was left unfinished. There was space, and we suspect the clerk may have been distracted for the moment and left the space blank. Fortunately, her name reappears following three other entries.

"Sarah Haines, d. of William Haines and Ann Haines, b. 16 July 1830, Tewkesbury, Cloucs. This Sarah is a daughter of William Haines St., and Ann Stone, and is a sister to Elizabeth Haines, wife of our William Wilkes, the younger.

"Elizabeth Wilkes, d. of William Haynes and Ann Haines, b. 18 Dec 1826, Tewkesbury. Baptized 12 Apr 1848, West Bromwich by William Broomhead. Confirmed same day. (Emigrated 2 Sep 1856) This is our direct ancestor, wife of William Wilkes, the younger. We may never know why she was baptized fifty miles away from Cheltenham. Her husband was a brickmason, and could have had work over in West Bromwich. This is but a speculation, but there is little reason to doubt that it was our Elizabeth. Note the date of her reported emigration.

"William Wilkes, son of William Wilkes and Elizabeth Wilkes, b. 25 April 1826, Tewkesbury. Baptized 28 July 1851 at Deerhurst by John Eyles. Confirmed same day. Emigrated April 1855. This is our William, the younger. Note his baptism was over three years following his wife's date of baptism. Why? It is interesting to speculate. Also, note his reported emigration date, sixteen to seventeen months prior to his wife's emigration. More will be said of this later.

"Hannah Wilkes, dau. Of William and Elizabeth Wilkes, b. 15 June (no year was given) at Boddington, Gloucs. Baptized at Norton." There seems little question but this is the balance of the entry mentioned earlier of which there was nothing but the name given. That this is the daughter of our William, Sr. and Elizabeth Hunt, can be particularly confirmed by her birthplace and birth year, as shown on the family chart on page 35. The chart gives her birth as 15 June 1825. Interestingly, she was baptized at Norton. We suspect it to have been Norton, Gloucestershire, a little parish about three miles from Cheltenham. There is another Norton in Worcestershire, which is considerable distance further away. We suspect, were it not the near-by Norton, the clerk would have so indicated.

"William Wilkes, ordained Elder 8 July 1852 by John Hyde."

And so ends the family-related entries in the Cheltenham branch records. Several excellent bits of information, which give us direction. The data revealed here answers some questions, but we have to admit new questions arise. We have already wondered about the West Bromwich baptism. Let us here agree that the first of us who goes to the other side, ask her. If that person who goes first wishes to be different, let him or her return and let us know.

And, Grandpa William, may we ask why you didn't lead your family into the Restored Church rather than your wife taking the initiative - hopefully at your suggestion? Could it have been that the Wilkes ancestral blood line carried an abundance of Ephraim's genes, but that the Haines' had an overabundance? Regardless, we of these three and four and more generations later, will always be indebted to Great-Grandma Wilkes and you, and others. You displayed great courage in accepting the gospel when, at the same time, you were well aware it was not the popular thing to do. Because of people like you, we who have been in the Church have had the occasion to compare its principles with the scriptures, and have had an opportunity not only to taste, but absorb the sweetness of the gospel message in our lives. The family and those who have been given what is, perhaps, but a glimpse of what awaits the true disciple of the Master, wish to express to you our most sincere and deep appreciation. We are very much aware that your position as vanguard to the Wilkes and related families was, undoubtedly, by previous assignment. Your generation consented to this assignment, to come to earth first to receive the brunt of the adversary's darts of disdain, persecution and hardship. We with our more timid souls, hope to meet you face to face, so that we can express our belated thanks. Hopefully, in addition, our lives will exemplify that degree of appreciation which will show whether or not our verbal expression is but "sounding brass and tinkling cymbal". We know you are as alive as are we. Please let us be assured that your prayers will always be for us, your descendants.

Now, let us return to the account of the years our great-grandparents were yet in Gloucestershire. William Wilkes, the younger, and Elizabeth Haines or Haynes, were married on the 15th of March 1846 at Tewkesbury.

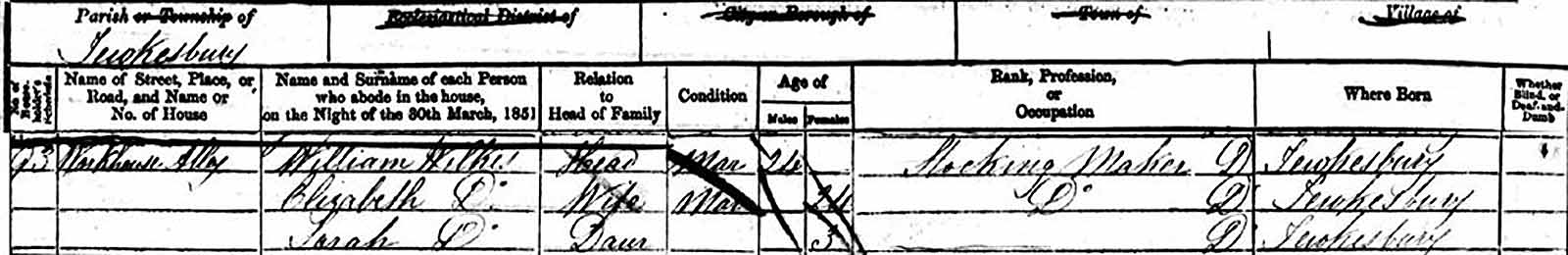

The 1851 census record, the first such record following their marriage, shows the following. It was taken on the night of the 30th of March 1851.

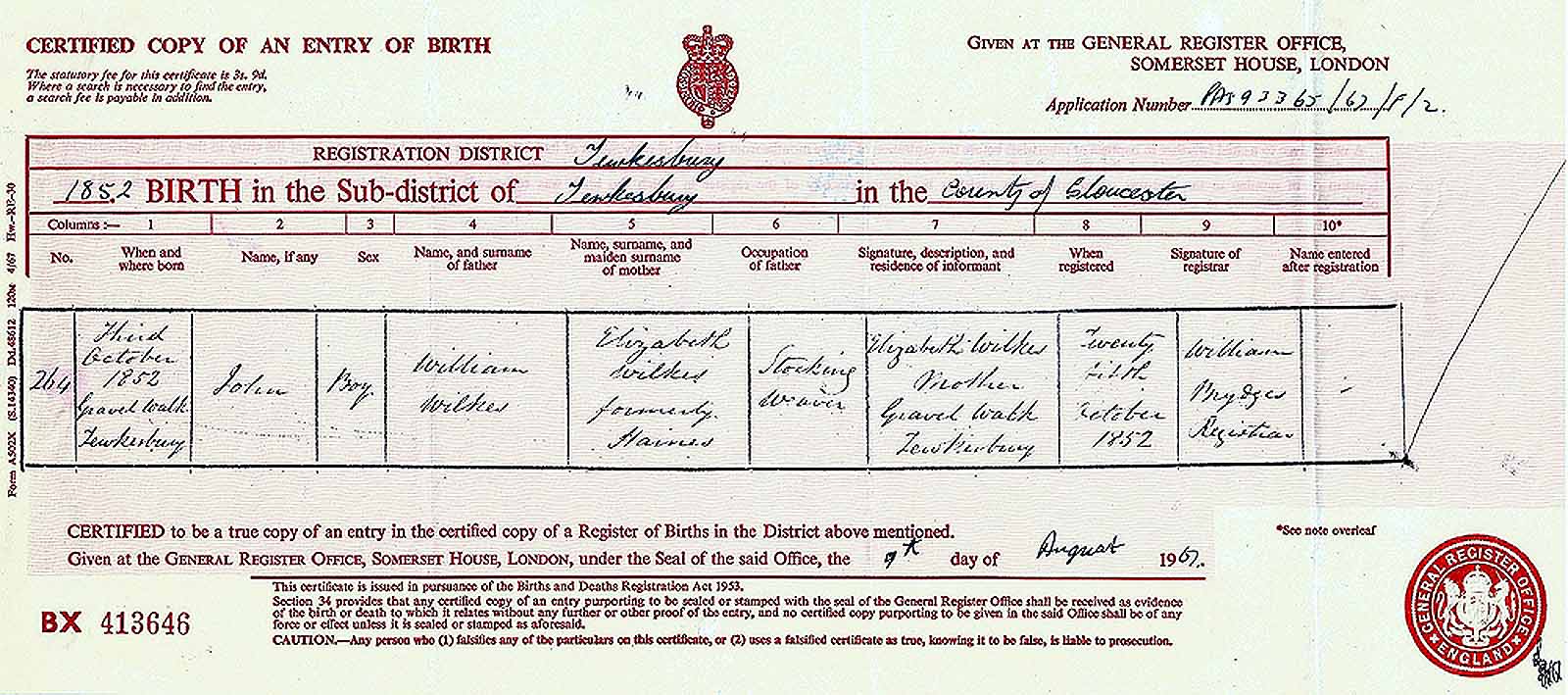

An item or two comes to light from the information recorded by the census taker: Their address probably doesn't indicate the poshness of the elite of England. The record of Sarah having been three at the time if probably more correct than the family records we have had through the years. The family records have long given 4th August 1850 as her birth date. It is hardly probably the census taker could have been in error. By the family record of Sarah Ann's birth, she would have been only eight months old on the night of March 30th when, in reality, her age was given as three. Another indictment against the reliability of a mother's memory. Securing a copy of Sarah Ann's birth certificate seems the logical solution to out problem, but such seems hardly important enough to warrant the getting. The census record above was too early for William's and Elizabeth's next child, our grandfather, John Wilkes. He was not to have been born until 3 October 1852, which date has been verified by a copy of his birth certificate which we have at hand. By the time of John's birth, the family residence had been changed to Gravel Walk, which may have raised of lowered the social status of the family depending on one's sense of interpretation.

William, the younger, has had us guessing over the years as to his occupation. It has been reported he followed the trade of his father, a brick maker. Now he told the census taker he followed the trade of stocking weaver. As we shall soon see, he personally reported four years later that he was a brick maker. From the nature of the two occupations, one's dexterity would seemingly be stretched to an extreme. Was William a master of many trades? We suspect enough to take care of his and his family's needs.

It was stated earlier that our second William became the family's first known Wilkes to migrate to America, and we have to rely almost solely on the records from the Cheltenham LDS branch.

Writing the story of an immigrant actually results in only a partial story at best. By rights, the story of a migrant can only be related as a biography, for a second party has no way of expressing feelings. First the original germination of the idea itself has to be known in order to tell the story. The impelling force behind such a move can better be felt than imagined, and three and four generations later, the relating of the story has to be limited to imagination.

What was the impelling force with William and Elizabeth? It has already been related that they joined the Mormon Church. It has also already been related that from apparent circumstances, as with the great majority of the families of their communities, providing a livelihood was a colossal undertaking. An undertaking that was quite discouraging, for there was little hope in the future at that time for improvement.

In the early years of Mormon missionary labor, the call was for the new convert to consider moving to Zion in order to strengthen the Church. During these years of which we have been discussing the Wilkes and Haines families - the 1840s and early 1850s - things were far from desirable for the families of the Church in America. The Saints were living in constant fear for their lives and property. Mobs were giving them no respite. The Church was being promised total extinction by their enemies. The prophet had been slain in cold blood and the Mormons were being driven from their own homes with never a hope of returning. In the dead of winter, thousands of families were forced to flee Nauvoo with the enemy's bayonets and guns at their backs. The Church leaders saw that they had but one option, to leave and cross the borders of the United States, their own country, whose constitution had guaranteed them freedom to worship as they pleased, and go to the Rocky Mountains in hope of safety.

These events were happening at the very time the Haines and Wilkes families back in Gloucestershire had found interest in attending the meetings at which the Mormon missionaries were relating their story. After having been convinced that what they were saying was true, the Haines and Wilkes families solicited membership. How long they had been in the Church before they reached the conclusion to go to the newly found headquarters of the Church - Salt Lake City - we don't know. Elizabeth had joined in 1848 and William had waited until 1851. If little Sarah Ann was three in 1851, as the census record states, then the mothers' baptism would have been near the time of the birth of the baby. If the family record of her birth is correct, then Elizabeth, the mother, would have been baptized more than two years prior to the birth of her baby.. Under the circumstances, we feel the census taker bears the greater credence. We get no assistance from the Cheltenham branch records as to Sarah. We find no evidence that children of record, as we know it today, were accounted for on the records, for no record is found of Sarah nor of their later son, John, who was born on the 3rd of October 1852. This latter date, which is from the family records, is confirmed by John's birth certificate:

According to the branch record, as was previously mentioned, the first of our family to emigrate was William. According to the note left on the record, his leaving the branch was dated, "April 1855". It was not at all unusual for fathers to go to America ahead of their families, for two probable reasons: first, to find work in order to obtain means to buy the family's boat fare, and secondly, to locate, at least a temporary home, as shelter for the family when they arrived. Seemingly this was the intent of Great-grandfather William, but in reality we know so little.

During these years, the Church was encouraging its members to move to Utah, not only by word of mouth, but it established a type of 'loaning program' known as the Perpetual Emigration Fund, which fund was contributed to by members all over the Church. Even little children who sometimes could only contribute a pence or two each week or month, were given credit on the branch records for their contributions, which was also true of their parents, who would offer all they could afford. IN this manner, a central fund in the Chi8rch was formed from which poor members who could not otherwise afford to buy boat passage, could borrow the amount needed, naturally with the intent of repaying as soon as possible after their arrival at their destination.

Also, depending on the number of immigrants leaving European shores at the same time, if there were sufficient, a Church immigration director, usually from Liverpool, England, western England's largest shipping port, would charter a section of a boat - on occasions an entire boat - from a shipping company. Depending on circumstances, these passengers would often be taken to a U.S. dis-embarkment port where facilities had been prepared in advance, in order to assist the passengers to move further westward toward Salt Lake City. It was not at all uncommon for their sailing vessels, after a month to six weeks being tossed on the Atlantic, to go to the mouth of the Mississippi, and there transfer to riverboats upstream to St. Louis. Perhaps from there up the Missouri to get to get inland by water as far as possible and make connections with wagon trains for the next thousand or more miles. Iowa city, Iowa was a popular starting point for wagon trains drawn by ox teams, and even handcart companies, more of which will later be written.

Too, the immigrants who disembarked from their ocean voyage in such ports as New York, Boston or other eastern city ports, would transfer to the railroad. Then they would travel westward to such places as Iowa City, in order to join with the main bodies of the Saints who were headed to the Rocky Mountains. During the years of the heaviest Mormon migrations, the railroad had been laid only to the Missouri River in the neighborhood of present-day Kansas City. During the decades of the 1840s, the 1850s and the 1860s, when so many thousands upon thousands of Mormon immigrants moved to the West, there was simply no other way than the wagon train or handcarts. It is true, a limited number of immigrants took boats from the east coast of the United States, and went around the southernmost coast of South America and sailed back up the west coast to California. However, this contributed little to the number in Utah, for after their boat reached San Francisco, they were nearly as far away from Utah as were those who left and traveled overland.

The railroad eventually reached Utah in 1869, which provided a much faster and safer means of travel. With the advent of the railroad, the wagon train epic came to a close, but only after leaving a long line of marked and unmarked graves of young and old, who were unable to survive the long ordeal of hardship.

The Cheltenham branch record stated that William Wilkes emigrated in April of 1855, which clue led us to search the boat he could have sailed on. By far, the most prominent embarking point was Liverpool, and it was to here that we turned our search. We concluded that he would not have remained in England long, so our search took us to the ships leaving Liverpool in April of that year. We found that during the month of April, three ships left Liverpool within the LDS emigration program. The first, was the sailing vessel, "Chimborazo", which had on board 431 passengers under the direction of Edward Stevenson, the leader of the company. This ship set to sea on the 17th of April 1855, with its destination to be Philadelphia. Among the names of the passengers on this ship, was Martha Eynon, age twenty-two, spinster, who was traveling with a family headed by William Rees, Sr., aged fifty-four. Martha was from Pembrokeshire, Wales.

When this name appeared, this writer was given a "start", for I had been searching for many hears for Great-grandma Wilkes, whose maiden name was Martha Eynon from Pembrokeshire. The thrill lasted only momentarily, for while I was still gazing at the name, I realized that the date of this Martha's being on board the sailing vessel was 1855. Our Martha Eynon had married and had three children, and was living with her family in Lake City (now American Fork) Utah in 1855. Our Martha Eynon (we shall write more about her later) was born in 1827, while the Martha Eynon on board the boat, according to the age she gave, would have been born in the year 1833. My thrill upon seeing the name was for the moment - like a silvery colored soap bubble, which was soon to burst.

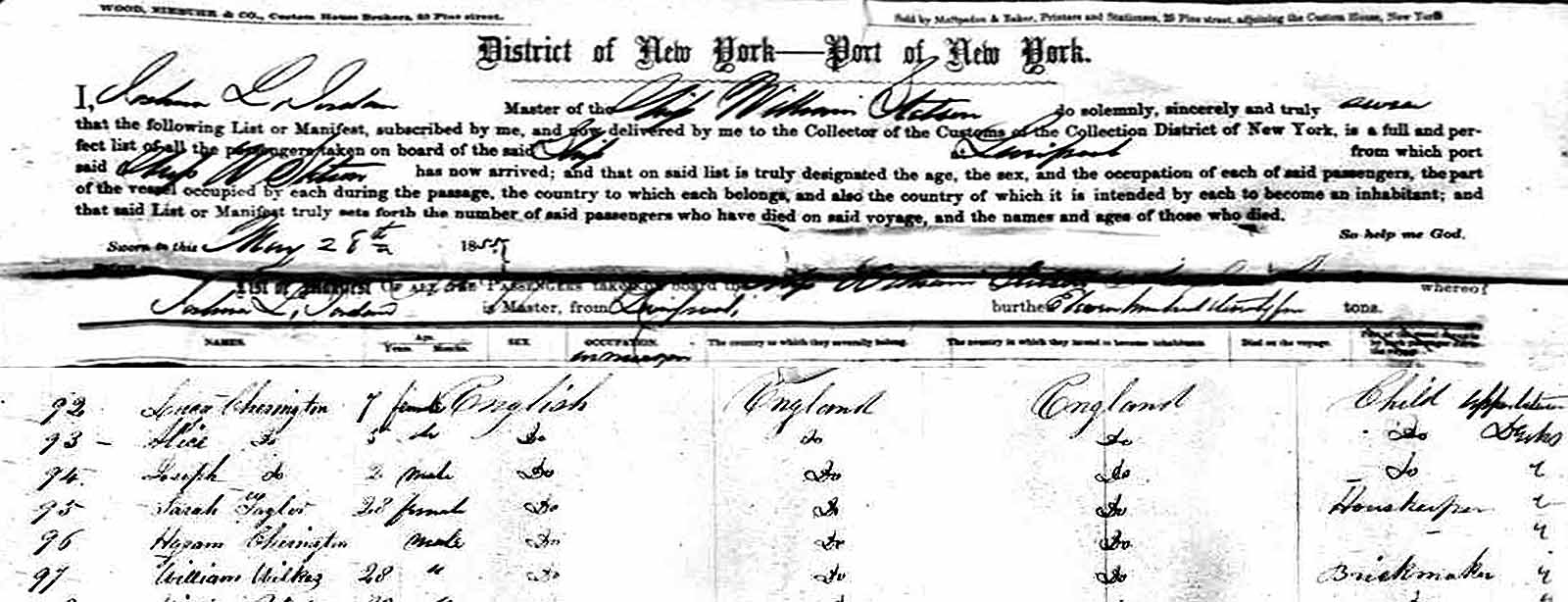

Continuing the search among the passengers of the three boats, which left Liverpool in April of 1855, the next was named the "Samuel Curling". This group of five hundred eighty one Church immigrants, was headed by Israel Barlow. This ship was to land in New York but contained no Wilkes name, however the third ship of the three presented the name of William Wilkes. The name of this ship was the "William Stetson", and its date of sailing from Liverpool was the 26th of April 1855. The number in the group, Two hundred ninety three, were under the direction of Aaron Smethhurst, and their destination was New York. The landing date of May 27th, is of interest. One can readily see plenty of time elapsed for sea sickness, although no mention was made of such happening.

Click here to learn more about the voyage of the William Stetson

The William Stetson was chartered by the church to carry return missionaries and converts from Liverpool, England to New York. They left Liverpool on 26 April, 1855 and arrived in New York 27 May, 1855.

Records of the journey can be found in the Mormon Immigration Index. The following information is from that index.

On the twenty-sixth of April, 1855, the ship William Stetson cleared from the port of Liverpool, and sailed for New York with two hundred and ninety-three Saints on board, under the presidency of Elders Aaron Smethust, Francis Sproul and William Wright. This was the last company of Saints forwarded under the American Emigration Law, and swelled the number of emigrants sent out by the presidency in Liverpool since November, 1854, to three thousand six hundred and twenty-six, of whom one thousand one hundred and twenty-seven came out by the Perpetual Emigration Fund. It is estimated that about one thousand five hundred of them reached the Valley in 1855, while the remainder located temporarily in various parts of the United States in order to obtain means to complete their journey to Utah whenever circumstances would permit.

The nationality of the emigrant was as follows: English, 2218; Scotch, 401; Welsh, 287; Irish, 28; from France Channel Islands, 75; Danes, 409; Swedes, 71; Norwegians, 53; Swiss, 15; Italians 15; Germans, 13; Prussian, 1. The William Stetson had a fair voyage across the Atlantic, and arrived at New York on the twenty-seventh of May. Two births and four deaths occurred on board.

The following image shows a portion of the passenger list for the William Stetson for the journey.

Passenger # 97 is William Wilkes from Tewkesbury, England.

This image shows William Wilkes as a member of the Mormon group on the ship

The boat's roster indicated that William claimed himself to have been a brick maker, and that he was traveling with two younger people, apparently a brother and sister team by the names of Ann Roberts, nineteen, a spinster, and William Roberts, twenty-two, a brick maker. The three of them were listed as a unit, # 44 on the passenger list, which indicated they were traveling together. Nowhere was it indicated that they were previously acquainted, however, the fact that both listed themselves as brick makers may indicate the possibility of their previously having worked together

The record of Great-grandfather William's whereabouts after his arrival in New York on the 27th of May, 1855, to the next date we have a record of him --22nd of September, 1859 -has been most elusive. Of the two or three possibilities, the one most probable would seem to be that he could have gone as far west as the railway had been constructed, which was present-day Omaha, Nebraska area, but probably remaining on the east side of the Missouri River in Council Bluffs.

That William may have remained here is but supposition. There were other places and situations he could have found himself in. As an example, he could have remained in the New York area and found employment in his own trade, or in any other area where brick was made. He would have gone where his masonry skills could be used until such time as his wife and two children would find passage across the Atlantic, which if we can rely on the suggested dates of their leaving England as recorded in the Cheltenham branch record - late September - his waiting period would have been seventeen or eighteen months subsequent to his arrival.

He may have concluded to join with the remnants of the body of the LDS Church members who had not yet been able to make the long land trip across uninhabited (except by native Indian tribes) prairies, deserts, and mountains. It was about a thousand miles between the Missouri River and the Salt Lake Valley. His option would have been with the LDS settlements, which were located mainly in Iowa between its eastern and western borders. These settlements were by design, at locations where families were invited by assignment, to spend weeks or, perhaps, months, in erecting temporary living quarters and developing farm sites, on which crops would be planted for others to later harvest a few months hence. In some instances, those who planted remained long enough to harvest their own crops, and in fact, at times, families would remain in one settlement for a year or two, or longer, until such time they, themselves, could continue the journey to Utah. A good example is Garden Grove to which we shall refer.

Also, such localities as Council Bluffs, Winter Quarters, Kanesville and Iowa City along the east and west banks of the Missouri River were literally beehives of activity. Therein private and Church sponsored business were set up for the purpose of outfitting wagon trains and handcart companies for the Utah journey ahead. We should also keep in mind there was need for like business activity in supplying others than the Mormon pioneers for trips west. There were those who had the urge to get to the gold fields of California, as well as the land-grant opportunities being offered for those who were willing to find homes in the vast spaces of the beautiful Oregon Territory. People were on the move, and by the middle of the 1850s, of which time we are attempting to follow William Wilkes Jr., there was a great lot of activity at the "jumping off" places along the Mississippi and particularly along the Missouri River.

Too, let us not close our minds to the possibility that William Wilkes felt it wise to go all the way to Salt Lake City and to prepare a home for his family in Zion. After all, this was the ultimate goal that the family had set for themselves prior to his leaving their homeland.

It is unfortunate, despite our considerable searching, we have not found the name of William Wilkes in any list of pioneers - Mormon or non-Mormon. But if he did find his way to Salt Lake, he was early enough in the year 1855 to have joined with a number of that year's wagon trains. The eight wagon trains of that season took a total of three hundred thirty wagons and two thousand seventeen persons. That particular year, wagon trains left Mormon Grove, Kansas, the only year in wagon train history that departures were that far south on the Missouri, on June 7th, the 13th and 15th respectively, all of which reached Salt Lake City during the first two weeks of September.

Whether or not William would have been able to travel inland from New York to the Missouri for any one of these dates, it seems quite possible. Four wagon trains left from the same place in July, and the first of these was made up of Church members who took advantage of the Perpetual Emigration Fund mentioned earlier in this history. There has been no evidence uncovered that would suggest the Wilkes family used this Church-operated fund. Certainly, there was no stigma connected with anyone's taking advantage of it, for it was but a means of borrowing from the fund with an obligation to refund it as soon as possible after arriving at one's destination.

The last wagon train of the 1855 season started its long journey toward the west on August 5th. This group was basically made up of those who used the Perpetual Emigration Fund from Europe. If William moved directly to his final destination after arriving in the US, it is not at all improbable he could have found himself with this group. There were four hundred fifty two immigrants with forty-eight wagons, who arrived in Salt Lake October 24th, approximately ten days less than three months, which would have been a good average, time wise, for the trip.

Let the reader again be reminded we are but reviewing some of the possibilities of William's having come west the first season after leaving England. No evidence is at hand to indicate he did not wait in the east or mid-west for his family. If, the suggested date on the Cheltenham branch records is correct, that she immigrated on the 2nd of September 1856, she would have been too late for moving on to Utah from the Missouri River that year. In fact, the last wagon train had already pulled out of Iowa City on the first of August. Eventually, this date proved to have even then been too late as the upcoming story will relate. The captain of this 1856 last wagon train proved to be none other than John A.. Hunt, whose half-sister was to become a Wilkes by her marriage to William Wilkes' son, John, seventeen years later.

Migration between the Missouri River and Salt Lake had proven difficult, but reasonably successful during the years from 1847 through 1855 and thousands of people were located in Utah by the immigration officials. However, a problem which had been showing itself for the past season or two, was becoming very real. Nor only the demand for wagons, horses, oxen, etc., etc., became greater than the supply, but more seriously, the cost was more than many families could afford. This was true particularly, of the poor of Europe, whose numbers were predominately from England.

A practical solution to this problem could be no other than for the migrants to walk. It was concluded that if light-weight carts could be built sturdy enough to withstand the rigors of the trip, rationed food supplies and other essentials for survival could be transported. So, such a push and pull system was resorted to and used by ten handcart companies beginning with the first company which started its journey on the 11th of June 1856 and the 10th company which left on the 6th of July 1860.

There were five such companies in the first year of this experiment, and it was but an experiment, which had both advantages and disadvantages to the wagon train, which will be discussed later in this history. Sailing vessels of the 1850s when the Wilkes family crossed the approximately 3,000 miles of the Atlantic were little different than sailing vessels had been for centuries. Four weeks in reasonably good weather were required from Liverpool to New York. Sea sickness and dysentry were common. Many trips were unpleasant from almost the beginning to the end. One way trips were sufficient for many travelers. Many also experienced a watery grave.

After reaching the Mississippi or Missouri rivers the Wilkes and Hunts had another thousand to 1200 miles of this type of travel which lasted from approximately three to four and one-half months in the case of John A. Hunt wagon train which didn't end untill long after snow-fall, extending from 1st August to mid December. Many travelers failed to reach his hoped for destination.

If William hadn't made his trip to Salt Lake in 1855, it seems quite unlikely that he would have made it during 1856, for if he hadn't done so during the first year, it would indicate he had made his mind up to await for his family. Again, this is but speculation. We can rest assured that if his wife, Elizabeth Haines and their two children, Sarah and John, were on schedule, they would have reached America sufficiently late in the season that their trip to Salt Lake, over the pioneer trail, could not have been earlier than 1857.

During 1856, there had been ten groups cross the plains, the first five of which would be classified as handcart companies, despite the fact that with each of those groups there were a few wagons to assist when emergencies arose. They would also carry the heavier supplies, plus provide a ride for those who became disabled, for such trips were not without injuries and sickness. Also, that summer, there were five groups classified as wagon trains, which were scheduled between the handcart groups.

At this point, this writer finds himself in a quandary. The original chapter, and indeed the nest three or four chapters, had been completed for several months, in fact, this and the two preceding chapters, as much as nearly a year. I had been continuously aware that I did not have answers to any number of details of the story, which resulted in a feeling of inadequacy. Actually, I was sharing all the information I had, but at the same time, I sensed the possibility of there being other data, which I had not yet located. Such a feeling resulted from many years of genealogical research work, wherein it seemed the data being looked for actually existed, and that it only became a matter of finding it.

As an example, it seemed there had to exist somewhere, the boat record of Elizabeth Haines and her children, Sarah and John, wife and children of William Wilkes. As the reader will recall, according to the Cheltenham branch records, Elizabeth was reported as having emigrated the 2nd of September 1856.

Considering this date as factual, this writer gave considerable concern and time to locate the record of her boat passage. The fact that her husband took passage from Liverpool, it was suspected this would be the route his family would take some seventeen months later. Commencing the search from that date, 2nd of September, the passenger lists were searched of every boat leaving Liverpool of which we had record. Nothing showed up. As weeks and months passed of searching, the thought that the record was there, but simply missed, as was very possible. Many of the entries were very dim, and in some instances hardly legible, so it was concluded to repeat the searches, but this time pursuing the task more slowly and more carefully. When one knows the record should be there, but it doesn't show up, it becomes somewhat disconcerting. The record failed again to show up. Not only the boats which left in September, , but all boats for the balance of the year 1856 were searched. Most of the boats had four to five hundred passengers, with an assortment from many of the countries of Europe, particularly the Scandinavian countries. Of course, there were also passengers from all parts of England. Each passenger, had been registered as he or she made appearance at the ticket office.

Realizing the possibility of their boat not being included among the lists of boats we had access to, and that the trip was actually made without us having access to one, another angle of searching was resorted to. Knowing that if she left England in September, there would be no way she could have reached the US in time to catch an emigrating group, be it handcart or wagon train, to go into Utah in 1856. Remember, the date of the last wagon train, which was later than the last handcart company was known to have left August 1, 1856. With this fact in mind, it was concluded that the whole of the Wilkes family, father, mother and two children, would probably be found with an overland group crossing to Salt Lake in 1857. In as much as they would have had to stay in the east for the winter, the family could very easily have been among the earliest of the 1857 handcart or wagon train companies.

The hoped-for good fortune of locating them from this approach, produced nothing in the first company, nor in any of the following seven companies of the year. Only the first two companies were handcart companies, the last six being wagon trains. Their record remained elusive. We were about to feel justified that this history had to proceed without Elizabeth's ship record. In fact, the history was continued for another few chapters, as previously indicated. Months passed, but the boat record continued to be a concern.

My wife, Mabel and I made a special trip to the Burley Genealogical Library, a regional library composed of six stakes, on the 20th of October 1983. We arrived at the library prior to 9 AM,, which was an hour before the morning shift was to commence, but our having the keys to the library made it no problem for us to get in.

It was not unique on this occasion to have had prayer, and always a prayer in our hearts, for this had been standard procedure through the years when doing research work, particularly on our own lines of ancestry. Mabel was searching on her own lines as she had been doing for well over fifty years, with considerable success. On this particular morning, as she was searching in the 1600s on one of her more than eighty possible lines of ancestry, she was using the IGI's (International Genealogical Index) reading machine. From it, she had obtained clues for searching in the ancient parish records of England. That very morning, she was successful in locating a couple of direct line ancestors.

On this particular morning, I had nothing especially pressing, but of late weeks I felt impressed to search Liverpool boat records prior to the date the branch record had given as her departure, 2nd of September 1856, the latest boat leaving just prior to that date. A mix-up of dates was not impossible, and I had no other direction to go, for I had checked and rechecked the boats following that date.

I had searched all boats leaving in September, so I actually started that particular morning's search in reverse, the last boat to leave in august, and the next last, usually three or four a month, until all boat records of August were searched. I would try one more month, so the last boat in July was searched until all of July was reviewed. My usual luck! This was afternoon by now. Mabel was not quite ready to leave. She never is, when she gets into those ancient records, but we had things to do at home.

I had time to do one more month of boats, but there was nothing in June. I had time to go through the month of May. Mabel was now ready, but I begged for a little more time. As I neared the spring of the year, the boat records were fewer and smaller, and I became reluctant to leave until I had finished the year. The month of May produced nothing, nor the month of April. It seemed I had had my share of disappointments, and I was but adding more disappointments. I didn't mean to complain, but I was beginning to think I had reason. March had nothing, and I had but two more months to complete the year of 1856. The Mormons didn't do much immigrating in wintertime, so it appeared. The boats per month were fewer. Mabel had been ready for awhile, but bless her, she has a world of patience, especially when it comes to leaving time in a genealogical library.

My reliance on hunches was rapidly waning, particularly in this instance, that Elizabeth's boat may have left ahead of the 2nd of September, the date given in the branch record. I felt a compulsion to see it through, however. As I recall, there was but one boat record for February, and as previously, I was going from the last of the month forward. The boat leaving Liverpool on the 19th of February 1856 was named the "Caravan".

As I was proceeding well through the list, all of a sudden, there appeared before my eyes the very thing I had been literally searching for years! I mustn't say I was stunned. Stunned is not the word, but that experience is hardly describable. One has to experience it. I don't have words to explain the feeling, the sensation, but "Eureka! Eureka!" and "what to my wondering eyes"! Yes, indeed, this was one of those rare occasions, which comes to a researcher who has searched and waited and prayed and waited and searched again! With control, I quietly whispered for Mabel. She was reading the next reading machine, and she came without delay. The elusive information for which I had been searching had been found. What a thrill! I have had such experiences before, but they didn't lessen this experience at all. I had wanted this information so badly and for so long. I had felt it had to have been somewhere, for the event was of such importance to my research.

Yes, relatively early on the afternoon of Friday, the 21st of October 1883, I at last, had before me this difficult-to-find data: "Eliz. Wilkes, age 29, a stocking weaver from Burton Court, Borden Street, Tewkesbury, England with two children, Sarah, age 5 and John, age 3".

As stated, they were passengers on the ship, Caravan, and had embarked on the 18th of February, and sailed away from Liverpool on the 19th of February 1856. The ship eventually arrived in New York harbor on the 27th of March. This meant that the ten additional days on the boat during February (this was a leap year, and that February had ten additional days from the date of sailing). Added to that, were the twenty-seven days in March, making the time they were on the water, a total of thirty-seven days to make the ocean voyage. Their trip required five days more than did the husband's trip ten month earlier, which was made in thirty-two days.

Comparing these two voyages, the extra length of time for the mother and children was to be attributed to the great ocean storm. Family tradition has brought the story down to us, as having been a real ordeal to Elizabeth, five year old, Sarah, and three year old, John.

Undoubtedly, it was the stories of this trip which caused John's children, at least my mother, Hettie, to have grown up with mortal horror of an ocean voyage. As recently as the writer's mission call to England in January of 1928, she was terrified of the possibility of my assigned ship, the SS Leviathan, then the world's largest passenger ship, sinking. However, it crossed the Atlantic safely in five and a half days. What progress within a little over seventy years from the little sailing vessel carrying a total of four hundred fifty seven passengers of Elizabeth's trip! That vessel had a carrying capacity of 1,362 tons, so it was reported with other information in the newly-found entry, whereas the Leviathan was advertised with a 60,000 ton carrying capacity.

What a contrast between the little sailing vessel, with few advanced features from the ships with which Columbus discovered America over three and a half centuries earlier, and the other, a great steamship with a passenger capacity of several thousand passengers! The latter was as comfortable as a great floating city, and yet, it had its seasick passengers as well. Undoubtedly, the trip on the little ship, Caravan, seemed to have lasted an eternity to Elizabeth and the two small children as it rose and fell with those huge, rolling waves of the Atlantic, during that almost mid-winter storm. As Elizabeth watched or heard of the burials at sea of those who lacked the strength to survive, she surely must have become frightened lest one or more of her family meet the same fate. Surely, it must have crossed her mind as to what would happen to her five and three year old children if she failed to survive this ordeal they were going through. Few of that type ship made the three thousand-mile voyage, especially in winter time, without one or more fatalities. In those instances, there was no other recourse than to lower the bodies into the wild waters of the sea. Fortunately, Elizabeth did not have to endure such a tragedy, which by the way, we shall read of later in this history, of one of our families, not specifically in our direct line. This ancestor buried his wife, the mother of several children into the dark waters of the Atlantic while immigrating to this country.

It must have been a great relief to Elizabeth Haines when the little sailing ship's passengers were able to see the coastline of the eastern shores of the US, their future home to-be.

Let us review the few facts the newly found passenger list reveals of our family. The recorded ages of the three passengers agree with our family records. The 1851 census of England, which gave Sara's age at the time of the census as three years (see page ) was in error. Census records often contain errors and this is an example, despite the fact that earlier I had expressed confidence in it.

According to the ship's record at the time of their leaving Liverpool, this Wilkes family had deposited toward their ship fare, nine pounds fifteen shillings with a balance of one pound three shillings, which we presume they paid before leaving the ship in New York. This would indicate the ship's fare would have been ten pounds eighteen shillings. No attempt will here be made to compare the value of the dollar to the pound as of 1856, however, as of the 1928 to 1930 rate of exchange, the pound was worth approximately five dollars. The pound was equivalent to twenty shillings, therefore, the ten pounds eighteen shillings was just short two shillings of totaling eleven pounds, or approximately fifty-five dollars.

We are still at a loss as to whether husband, William, after his landing in New York on the 27th of May 1855, remained near the east coast, or whether he continued toward the west to the Mormon's departing places for Utah. There were several places of departure from which the Mormon immigrants started their land trek. Some left from the Mississippi River area, such as Iowa City, Iowa, Council Bluffs, or during the years of 1847 and 48, Winter Quarters, near present-day Omaha. As the railroad was extended westward, the distance traveled by the wagon train and handcart companies shortened until such time as the railroad reached the Salt Lake Valley in 1869.

Until we are able to locate the record of this family crossing the plainsAccording to the obituary of John Wilkes and a history of Sarah Ann Haines, Elizabeth Haines Wilkes' sister, the family stayed in Delaware for a year. They traveled to Salt Lake City as a part of the Jacob Hofheins Company, consisting of people from Delaware and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania which left Iowa City, Iowa 6 June 1857 and arrived in Salt Lake 21 September 1857.

Ruth Blacker Waite , we may never be assured whether William waited for his family to make the last leg of their journey. It seems so logical that he would have waited, perhaps most likely in Iowa City, Iowa. With Elizabeth and the children arriving in New York May 27, 1856, we can feel quite assured that the trip across the plains would have been sometime during the summer of that same year. The first group to leave for Utah that year, was a handcart company of two hundred seventy five souls, who left Iowa City with four wagons, fifty-two handcarts on June 9, arriving in Salt Lake September 26th.

Undoubtedly, Elizabeth would have boarded a train following their arrival, and travel westward as far as Iowa City, with time to spare in assisting in the preparation for the trip. It would seem that her husband would not have gone further west prior to their arrival. It is recognized that in far too many cases, the existing lists of names of those forming companies, is incomplete. Our conclusion is that our family has to be among those with names missing.

Two days following the first group leaving Iowa City, the second handcart company left the same place, this on June 11th. This company had two hundred twenty two people, with four wagons and forty-eight handcarts. They arrived in Salt Lake City, the same day, the 26th of September, as the company which started two days earlier.

On the 23rd of June, the season's third company left the same place with three hundred people, along with five wagons and sixty handcarts, arriving in Salt Lake City October 2nd. In retrospect, it seems the Wilkes family must have been numbered among one of these three groups. Considering the amount of time they had since arriving in New York, it seems not too far fetched to believe such a schedule would have been very possible.

The next two companies leaving that season, were also handcart companies. The Willie Handcart Company, which left Iowa City July 15th had five hundred people, with five wagons and one hundred twenty handcarts. The Martin Handcart Company left with five hundred seventy five people and seven wagons and one hundred forty six handcarts. These last companies were unfortunate in that they became the two ill-fated groups which were trapped by the early winter storms in Wyoming, and required being rescued by teams from Salt Lake. More will be mentioned of these companies later in the story.

Aside from these five handcart companies, five regular wagon trains were, likewise, on the way to Salt Lake. Three of these groups left from Florence, Nebraska on June 5th, 10th, and 15th. They contained two hundred, three hundred twenty, and three hundred people respectively. The William Wilkes family could well have been with any one of these three wagon trains, if they were not with the handcart companies. Two additional wagon trains left Iowa City, both of these following the last handcart company. They were involved with the last two handcart companies in the early, but severe winter storms mentioned earlier. The last of these groups did not reach Salt Lake until as late as December 15th. The rosters of these last groups have been examined with no Wilkes' names. More will be written, especially of this last wagon train, for its captain was John A. Hunt, a half brother of our grandmother, Martha Hunt Wilkes.

We strongly believe, but as stated, have no solid proof, that the Wilkes family made the trip across the plains in one of the several possible LDS Church sponsored companies. However, we must not overlook the fact that there were numerous other, usually smaller, wagon outfits following the same general Mormon trail which were not connected to the Mormon sponsored companies. The federal government had just opened up incentives for colonization in the great Northwest, including the Oregon country. People by the thousands were getting involved on a smaller basis than the Mormon movement of colonization. Too, we want to remember we are not too far removed in time for the 1849 gold rush to California to have come to an end. Other gold fields were being found than the original at Sutter's Mill, which actually had been discovered by some Mormons who were returning toward Salt Lake, after being mustered out of the Mormon battalion in California.

Our William Wilkes family could have crossed the plains in 1856 by either wagon or handcart. Actually it is quite possible and even probable they came by the latter. During that year there were approximately 1,872 came by handcart and approximately 1,270 by wagon train. Either way there would have been much walking.

There were mixed feelings among the Mormon migrants toward these other folk traveling in the same direction. One of the major problems in the overall westward movement by anyone, was the grazing provisions for the animals. This included the animals pulling the wagons, and the riding horses, as well as the livestock being driven along to provide meat as well as to be used as breeding stock after the immigrants had reached their destination. Too, the non-Mormon people, and particularly those heading for the gold fields, were a rougher and tougher breed, who in their hurry to get to California, offered little or no consideration for others. On the other hand, due to their hurry, they often had excess goods, which they were willing to dispose of for a reasonable or no price. This was particularly true after the Mormons had a settlement in Salt Lake City.

The purpose of mentioning this other traffic toward the west, is that even some Mormon pioneers traveled independently, or in small groups such as three or four wagons made up of a few friends, with no ties to the regular organized companies. Many of these small independent groups from among the ones heading for Oregon and California, began traveling alone, but due to Indian dangers, most of this type traveler joined the regularly organized companies for protection, especially for night time camping. These independent travelers would never have had their names included on the roster of names of those belonging. It is not mentioned here to infer that the Wilkes family may have traveled independently. Such was done by more than we would normally realize, but with the Wilkes having had little or no experience with animals and wagons, etc., surely they were sufficiently wise as to not take such chances. The method was mentioned because there were such groups, perhaps well equipped groups, who didn't want to be hindered by being with a large group.

Hopefully, it has been made clear that attempts have been made to locate the Wilkes family somewhere between their leaving the boat in New York, William on May 27, 1855, and his wife, Elizabeth and children, leaving the boat on March 27, 1856, and a known date when we are able to pick up their history after arriving in Salt Lake City. First, we now turn to family history in the possession of their descendants.

In a history of her father, John Wilkes, Aunt Mabel Wilkes Brown relates: "At the age of about six (remember the boat record says he was three) he sailed the Atlantic Ocean in an old sailing vessel with his parents and one sister. (The boat record says mother and sister) Father traveled a lot when he was a small boy. After they had arrived in Salt Lake City, they went South with the move of the people at that time."

This last statement may require explanation. From the commencement of the Mormon Church, there was willful persecution, which stemmed mainly from religious leaders who were resentful that Joseph Smith, through instructions from the Lord, reported that they were assuming authority in their ministries which they did not rightfully possess. Secondly, there were many people who, due to the lack of proper information, had been led to believe that the Mormons were but a radical sect or cult, that did not believe in the Christ as the Bible taught. In addition, they wrongly believed that in place of the Bible, the Mormons had concocted a volume of scripture of their own, known as The Book of Mormon. This claim was not at all true.

The Mormon people, while yet in the east and Midwest, had been maligned, persecuted and literally driven from their homes in the states of New York, Ohio, Missouri and Illinois, by mobocrats and violence. In desperation, these persecuted people sought refuge beyond the boundaries of the then United States, and after their arrival in the Salt Lake basin, mounted the Stars and Stripes as their continued ensign of freedom, which had been guaranteed them by the God-inspired constitution.

After arriving in the West, the Mormon people declared the area into which they had moved as "The Territory of Utah". Naturally as a part of the United States, which technically was beyond the western boundary of the United States and within Mexican territory. They selected Brigham Young as their new governor, and continued to declare themselves as citizens of the United States. Such a selection of governor, while not wholly approved by official Washington, was condoned perhaps due to distance. With malicious intent and through false accusations as late as 1857, complaints reached federal authorities of insurrection in Utah. Without investigation, the War Department, with the approval of President Buchanan, organized and dispatched a military force toward Utah. Accompanying this expedition was a presidential appointee to replace Brigham Young as governor, if not peacefully, then by force.

The difficulty and slowness of communication in those days, and the isolation of the Mormons in the far-off Utah valley, made it possible for this US army to be well on its way before the Utah people were aware of it.

When word of the coming of the military eventually reached Brigham Young on the 24th of July 1857, while at a public celebration of their tenth anniversary of the arrival of the first Mormons in Salt Lake, they were very much surprised. Long prior to this, the Mormons had concluded that never again would they succumb to the threats of violence forced upon them prior to their coming to the peaceful valleys of Utah. If such were to be their lot again, they would fight.

Within the next few days, the word of the army's coming was confirmed and now the worst could be expected. Let the reader not overlook the fact that the William Wilkes family was now in Salt Lake City, and undoubtedly by now had their home. Just where, we are not aware. Salt Lake City had become sizable within these ten years. Later in the history, a picture is shown of the city in 1853 as of chapter five. Even by that year, it was hardly believable.

After meeting in public gatherings to get the consensus of opinion of the people at large, the Mormon leaders issued the decision that should the army come into the valley with any indication of force, they would find nothing but desolation. The decision was made that rather than submit, every family would prepare their home to be burned, and likewise, every business and public building would be prepared for a match or torch. The army would find nothing but the ashes of their burned homes, schools, churches and crops, etc., and the people having fled "south" into the Provo area and beyond.

As the army neared Salt Lake City, the hundreds upon hundreds of families prepared for their "scorched earth" policy to be enacted in order that nothing be left which would be of the least worth to the invading army. All that was left to e done was for the small selected group of men, upon seeing the armed forces coming, was to light their torches and go through the city to start the buildings, houses, barns, sheds, also hay and straw stacks, afire. Already, the great Salt Lake temple, which had been started two or three years before, and whose walls were beginning to rise above the edge of the deep foundation, had been purposely torn down below the surface of the ground. It had been filled over with dirt, which was plowed to make the lot resemble a newly plowed field. The Mormons meant total destruction, if such were necessary.

Prior to this time, the Utah militia also took the initiative by traveling eastward toward the oncoming army, and applied the "scorched earth" policy by doing all they could to hinder the advancing enemy forces. They set fire to as much grazing possibilities as possible, for the army was depending on horses for its mobility, and cattle to be slaughtered for food as they moved forward. The Utah militia actually got as far east as Fort Bridger, Wyoming, prior to the army reaching that point. This fort, and Fort Supply, which was close by, were both owned by the Church, and both were burned to the ground to prevent them being utilized by the United States Army, this in October of 1857.

By the time the army reached these burned-down forts, it became very much aware of the fact that, with the handicaps they had to face, that it would never reach Salt Lake that year. Under cover of darkness, daring Mormon scouts on occasion, had penetrated the army camp and set fire to some of their supply wagons, the whole intent being to delay the army's progress as much as possible.

Such tactics on the part of the Mormons, revealed to the army officials and the US government that the Mormons were not going to be intimidated. As a result, communication was started in so much the President Buchanan appointed a peace commission to meet with Brigham Young and other Mormon leaders. By doing so, it was discovered conditions in Utah not to be as bad as earlier reported. This last suggested meeting was held in June of 1858 in Salt Lake City after the Mormon families had already moved "south" into the Provo area. The US investigating committee was astonished to find so large a city with its inhabitants already fled. They were amazed to find that in many homes, furniture had already been stacked in the middle of the living rooms, and kindled ready for the touch of the torch. To their surprise, the commission found the Mormons not guilty of any nature of treason or rebellion and a pardon was offered and accepted by Brigham Young. Had it not have been for the Mormon tactics in delaying the army ,so as to give time for communication, the final outcome could have been much different.

And so, William Wilkes and family with the thousands of others were signaled to return to Salt Lake City to their respective homes, which they had left a few weeks before. They had not known at the time, whether their homes would be standing if and when they were ever to return.. Such is a brief explanation of Aunt Mabel's comment, "After they arrived in Salt Lake City, they went South with the move of the people at that time."

Aunt Mabel's account of the Wilkes family continues, "In 1859 they came clear back to Logan, Utah." Before this moving to Logan, however, there is an event Aunt Mabel failed to take into consideration, if she ever knew. Our William entered into the practice of polygamy, with which subject we shall start the next chapter.

AN ADDENDA TO CHAPTER THREE

After nearly completing the entirety of this history - many months following the writing of Chapter 3 - while writing of the death of Grandpa Wilkes (John) I turned to the newspaper copy of John's obituary, which copy I have watched over -- it being in my Wilkes family file - for the last fifty-six years. Over the years I had occasion to browse through it and a note of interest glared back at me. I now wonder why it had not registered with me before.

My first thought was that it would now be advisable to rewrite the entire story of William and his family - wife Elizabeth Haines and children, Sarah Ann and John - completely over. The newspaper obituary appeared to have the answer to the problem over which we have been struggling with these many years. The big question as the reader by now has realized, with William having come nearly a year earlier than the rest of his family. Did he remain in the east to await their arrival? Two or three alternatives were pondered over and discussed in the last few pages. To rewrite the entire story seemed a monumental task. The writer whose health has not been the best for several months, simply felt I didn't have the strength. I concluded to not attempt to rewrite, but to leave the pages as written and bring forward in this addenda what the discovery was as described in the newspaper's obituary. The complete obituary will be left to its proper place in a much later chapter. The portion of it relating to our problem, reads, speaking of Grandpa John, crossing the ocean as a child, "He crossed the Atlantic, and stayed one year in Delaware, then came to Salt Lake City."

So far as I am aware, none of the children have mentioned "Delaware" in any of their written histories of their father, yet, they apparently were aware of it, for whoever gave the obituary information to the Star Valley Independent, was aware of it.

This statement creates another series of suppositions. While Grandpa John was between three and four years of age at the time of their landing in New York, the boat record of the landings of William, and his family nearly one year later, shows New York City to have been the port at which they both disembarked. Delaware is on the seacoast, but down the coast a couple hundred miles. Can we suppose that William spent the time since his arrival in Delaware? Does the obituary mean, as it says, that John as a little boy, with his family, spent another year in that place?

Delaware appears to have been a side trip from the normally traveled route to the take-off points from either the Mississippi River or the Missouri River en route to Utah, so we can wonder what took the family down to Delaware?

There was a lot of immigration from England to the United States during those years, and not necessarily for the Church. Could it be that William had a friend who came to America and settled in that area? We may never learn why, but we have no reason to question the informant who passed the information on to the paper for the obituary.

If the family stayed in Delaware a year after the mother and children arrived in New York March 27, 1856, then their overland trip to Salt Lake would not have been made before 1857.According to the obituary of John Wilkes and a history of Sarah Ann Haines, Elizabeth Haines Wilkes' sister, the family stayed in Delaware for a year. They traveled to Salt Lake City as a part of the Jacob Hofheins Company, consisting of people from Delaware and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania which left Iowa City, Iowa 6 June 1857 and arrived in Salt Lake 21 September 1857.

Ruth Blacker Waite Even so, they were in time for the move south.