An account of one's ancestry is not a simple subject, nor is it short. The Biblical account of Adam, the first man, is reported to have had its start some four thousand years prior to the Savior's birth, and subsequent to the latter event, another two thousand years have passed, totaling approximately six thousand years. Our Wilkes ancestry, then, stems back that far in time as does anyone's ancestry.

Were we able to complete our pedigree chart the full length of that long time, we would have approximately 180 generations. By rule of thumb, three generations will cover a century. Fortunately - or unfortunately according to one's viewpoint - records are not available for most families to trace ancestry for more than approximately 500 years back from the present into the past. There are a few exceptions of families with connection to lines of royalty, but even with these pedigrees, most if not all lines, lack sufficient proven evidences for there to be any degree of certainty of validity.

The span of time is too extensive to depend on records and this, particularly between the periods of medieval and ancient history. There are some families who will contest such a statement, and will attempt to defend their claim to accuracy of pedigree to Adam. Most, if not all professional genealogists insist this is but wishful thinking.

For one to have such a pedigree, two factors have to be faced. Most royal family pedigrees are established by only those who have occupied the throne. Not all successions are from father to son, or from son to father, if one is reading the chart from the other direction. On occasions kings and queens have been followed by a brother, a nephew, a cousin, or, perhaps, even an unrelated person. In ancient pedigrees with no substantiating history to come to the aid of such a claim, documentation is having to be ignored.

Also, most ancient pedigrees facing the above problem very often miss one or perhaps, several occupancies to the throne, such as in the following example: "---to Odin, 70 BC (a king of Asgardia) who was 41st in descent from Eric, (King of Scandinavia) 2,000 B. C. " It can readily be observed that such pedigrees are far from complete. In this instance, even if ascent could be proven to such a one as Odin - which it can't -the long gap of 41 actual occupants of the throne to a proven line coming from the other direction leaves an unsolvable situation.

Fortunately for us of the John Wilkes' family lines, we face no such problems. Seemingly, our ancestry is of the common families of whom there has been such an abundance. Actually, there is no need to glory in the fact that there some who have proven direct descent from Royalty. It can be guaranteed that within twenty generations, every living person will have discovered a connection to royalty on one or more of his pedigree lines. There is the fact too, that there are royal families to whom a connection would not necessarily be flattering.

All of us have ancestry and surely it must be a rare individual who can honestly say that he has no interest in them. Those people who are numbered as being among our family ancestry, have lived their lives and despite the fact that they are not of our own generation, have claim to our interest.

Often we have to search to find their tracks - who they were and from whence they came - but such is a pleasant challenge. Were we to have a personal acquaintance with them - any one of them - there is little doubt but that we would have respected and loved them. We gain such a supposition with our parents and grandparents, and this sense of affection is confirmed over and over again by observing our grandchildren's love for their grandparents, and also conversely, the grandparents' love for them.

What is true with us has to be true with the generation before, two generations, four, ten. We love most those closest to us, and all we have to do is to close our eyes and imagine ourselves as a child in a home of any number of years ago. That child, it goes without saying, loved his or her parents, and if he or she knew the grandparents well, almost without exception, we can be assured there was an overwhelming amount of love. Let each of us transpose our self into any and all the preceding generations, and even though it be by proxy, our own love for any one of our ancestry will become genuine. As we proceed to become better acquainted through this family history, surely our love for any one of them will become a reality. Each of them were once sons or daughters, each of them were once parents of their children, and as the generations passed, became grandparents, great-grandparents and on and on. Such is but a process of life.

Time on earth is such that personal acquaintance is not possible beyond a very limited number of generations. From one extreme to another, there are a few who never see or are ever given an opportunity to become acquainted with their own children, or their own parents. This is regrettable. Naturally, such situations are limited as compared to those of us who are born and reared in the homes of our own parents. Under such a situation, children and parents develop bonds of love for each other which we often classify as heavenly, a term we use to denote as our hope that there will be no end.

Such a relationship, very often, is real into the next generation - between grandchildren and grandparents - to which the three generations so involved respond due to personal acquaintance and personal association. This then, brings up an interesting phenomenon, that we become more interested - one's love becomes deeper - in those with whom we are the better acquainted. Family togetherness, it is called in the parlance of modern-day speech. Is it any wonder that grandchildren have a special yearning to grow up in the vicinity of their grandparents - and conversely? When circumstance does not permit, then such substitutes as an occasional visit, letter writing, telephone calls, family reunions become next best. The important factor is that family members, whether within a specific generation, or a cross-over from one generation to another, should insist on a means of 'keeping in touch'.

Skipping a lot of important comment on the point being made of immediate family members keeping in close contact, we but have to expand the circle in order to see the advisability and need for family reunions. Most fortunately, the children from the John Wilkes-Martha Elizabeth Hunt marriage, who were yet alive by the decade of the 1920s, namely Aunt Mattie Walker, Uncle Ed, Aunt Lottie, the writer's mother, Hettie, Uncle Noen, Aunt Lola Holbrook, and Aunt Mabel Brown, saw fit to unite in a family reunion program. This called for a family get-together at least on an annual basis. To these reunions, all descendants of John and Martha Wilkes were to be urged to spend at least a day at alternative places, for the purpose of renewing family friendships, and socializing for a brief period while comparing notes relating to family records.

By the middle of the 1930s the urge for the need of gathering ancestral records fell heavily in the minds and on the shoulders of these brothers and sisters of the John Wilkes family. More will be written of each of these brothers and sisters, later in this history, for they were an exceptional family so far as their love and regard for each other. They loved the Lord and they loved the Church despite their quiet and retiring natures. They were not of the disposition to assert themselves to even so much as wish themselves into roles of leadership, other than within their own homes, but they became most faithful as to any assignment they may have received. Their desires were to do what they could within their family, Church and community.

While none of them lived near a temple, everyone of them sensed the spirit of the temple in that they strove to seek its blessings, not only for themselves, but also yearned that their children and children's children would live for these blessings. Nor was this deep, trusting yearning for the living alone. They sensed that they had a real obligation to see that their ancestry could share in every blessing of the temple.

They sensed that the most practical way to accomplish this was to pool their resources by creating a family organization, which they did. This resulted in The John Wilkes Family Organization, with the eldest brother, Ed, serving as president with other officers to assist, including youngest sister, Mabel, to serve as secretary.

Dues were felt to be essential, for it was felt there would be expenses. It was felt that after the families had pooled all their respective genealogical records of their two or three known generations of ancestry, it would become necessary for correspondence to the Salt Lake Library, and then, perhaps, even to England. The family was well aware that their roots were in Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, England, from whence their father, John Wilkes, with his sister two years older than he, Sarah Ann Allred, accompanied their parents to immigrate to this country. The parents were known to have brought their only two children when they small. After a hard crossing of the Atlantic in a sailing vessel requiring several weeks, they joined a wagon train or a handcart company and crossed the plains with great hardship.

The writer, even though present at the time of the organization, does not now recall the amount of dues called for. Remembering that it was during depression years, and the families were struggling, the suggested assessment for those classified as the 'first generation' was probably $10 per family. There is a possibility that it was $20, but I am fearful that would be too high. The second generation who were married, were invited to contribute $5 annually. And so a start to unitedley gather genealogy was made.

The Wilkes surname is not what one would classify as an altogether uncommon name. Almost everywhere one goes, he can fine the Wilkes or Wilks spelling of the name in most telephone directories of England. The difference in spelling means little, however, most of our families have spelled their names, WILKES

Interestingly, every Wilkes surname on our particular family pedigree indicates having been christened in the city of Tewkesbury, excepting the earliest Charles, who was born about 1740, but who's christening date has, to this day not been located. We have evidence, however, that he lived in that city, for his children were born there. His wife was christened in Tewkesbury in 1741 - Elizabeth Bradley - and as will be explained later in this history, her father came from a place afar and married her mother to be. It will be noted later that this and other allied lines, which married into the Wilkes family, have given us a lift in extending our pedigree, in an instance or two, five or six generations beyond the earliest of our known Wilkes family. For this we will have to go elsewhere than Tewkesbury.

In our desperation to find records of our ancestral families, we sometimes become overly critical and wonder why more care was not taken in recording and preserving records. We often overlook the fact that people living in these early centuries - the sixteenth, the seventeenth, and even the eighteenth centuries - were living in an entirely different world than those of us in the last couple of decades of the twentieth century. Those who could read and write were in the very limited percentile of the total of the population, and record-keeping had to be done if it were done at all, by these few. Too, the necessity for record-keeping may not have been understood by the few who could have taken care of this important chore - and chore, undoubtedly it was.

While some parish ministers and clerks kept records much earlier. It is to be understood that prior to 1538, it wasn't required by law. As can be expected, far too many local church officials failed to keep records, or if kept, records were not considered of such importance that even reasonable preservation practices were adhered to.

It is not difficult to understand the problem facing a local church official, who may have fallen heir to a church strong-box. That box, such as a modern cedar chest, had been filled to overflowing with the records of his predecessors. Often attics or basements, or other crowded storage rooms were needed for the storage of more recently obtained church paraphernalia. The question naturally arose as to what to do with the already one hundred year old box of christenings, marriages or death records. These, perhaps, had already housed generations of mice or rats, and were already partially destroyed by the seepage of water into a basement, or if stored in an attic, those records had been damaged by the rainwater from a leaky roof, which, in rainy England, is not at all unthinkable.

So, undoubtedly, back in the fifteenth, sixteenth or seventeenth centuries, a perplexed vicar, rector, churchwarden or clerk would think to himself in desperation, "What good to anyone is that old, already half destroyed box of records, now fifty, a hundred or more years old?" Surely a modern-day housewife would not have been pressed to such an extremity before a house clearing day would be declared. So, likewise all too often, ancient records became a part of a Guy Fawkes Day (November 5th in England) bonfire demonstration This date was annually observed in honor of an attempt made long before, by a political dissident to burn the British houses of parliament as his way of showing dissatisfaction of "Strong-armed" British rule.

Little did these perplexed church officials, perhaps caretakers only, realize that centuries later, people like you and me, in our attempt to become acquainted with an ancestor, would be willing to give anything we had for a few, even a single, entry from that strongbox, which so long had been stored, usually under a lock and key.

Fortunately for us, there were some government and church officials who anticipated the true value of these records, and they took steps to preserve them. First, steps had to have been taken to have such records recorded, as has already been indicated. It became an official church responsibility in 1538, when the government made it mandatory for such records to be preserved for the purpose of assisting the government in keeping track of its citizenry. It was not until the first day of July 1837, that regulations were set up for vital statistics to be kept by the government itself, this in England. Since that date, all births, marriages and deaths are required by law to be reported by the families involved with such events. The previous requirement for the church to keep records has never been rescinded, so since that day, there has actually been two sets of records - the church records and the state records, which has greatly increased chances of locating a record of one's ancient family. Of the millions and hundreds of millions of names having been recorded somewhere, and having been preserved by law, the question now facing a researcher is not so much, was the record originally made, but where can the record be located?

Under these required sets of records, and the many other possibilities for an ancestor to have left his name, it is not likely many have lived but that his name and other data can be uncovered. The challenge is, where?

After this digression of the past several paragraphs dealing with the recording and preserving of records, let us now return to the subject formerly at hand - the story of our closer-in-family of a generation ago.

Our pedigree chart, which has become the skeleton or outline of parentage from generation to generation, has required a goodly number of years of research. As previously stated, the children of John and Martha Wilkes concluded to name the organization, and so it was officially registered on the records of the Genealogical Society of Utah, as "The John Wilkes Family Organization". The family's pedigree, at the time - mid 1930s - was rather limited to about three generations on the Wilkes' line and about the same on the Hunt Line.

The writer of this history had the good fortune of being appointed by the new family organization, to direct the affairs of research and handle the money that annually was subscribed by the families for the sole purpose of hiring professional help where necessary. A year later, upon our marrying, my wife, Mabel was invited by the organization to assist me.

Our first goal was to secure from the family, the records already compiled, and from there to extend the record by searching materials available in the Salt Lake Library. In as much as John Wilkes himself, as a boy, but with his parents and sister, emigrated from England, family records on this side of the Atlantic were relatively few. This simply meant that most of our research had to be done from England. Letters were written to the parish ministers asking for their charges, and later, for specific searches to be made of periods of time, usually five to ten years for christenings, and marriage dates of specific individuals. Limited success was received by this process. During this period of time - in the late 1930s and the 1940s - the Genealogical Society of Utah was actually in the business of doing professional research work for patrons, naturally for hire. They had a superintendent of research with professional researchers at the library, as well as those "in the field" in various areas of England.

With permission from the officers of the John Wilkes family organization, some of our research was turned to the Genealogical Society - this about in 1940 - and from that time we coordinated our personal research efforts with the professionals, turning over to them reports of the results of their findings on a regular basis, which for many years, averaged about once a month - sometimes once every two to three months, and often, two or three times each month. Naturally, there were charges. As mentioned earlier, the family organization regularly at every annual family reunion, welcomed voluntary contributions toward research work which ranged from seldom less than one hundred dollars, up to two or three hundred dollars a year. The total of these contributions were sent to the Society, and with each of their reports, the cost and the balance were reported. It was not at all uncommon for the family funds to run out before the next reunion, whereupon contact was made with us, and members of the family sent additional contributions. So far as can be recalled, there never was a time between 1935 and 1980 that the account between the Wilkes family organization and the Genealogical Society was closed due to the lack of funds.

One of the Society's professional researcher for Wales from where our Eynon and Griffith families sprang was David Gardner who had specialized in Welsh research. He was an Englishman by birth and while yet over there was hired by the Society, but within a few years his experience was noted and they invited him to immigrate to better serve the Society from its home offices. For several years David directed our Welsh research. The Wilkes' research of the branches of the family living in England proper - Gloucestershire, Worcestershire and Shropshire in particular - had been assigned by the Society by the mid 1940s to another professional researcher, Frank Smith, a native of England. Due to his proficiency in English research, he likewise, was invited to immigrate to Salt Lake by the Society in 1953 and soon after, he was called to serve as Superintendent of Research, which position he held until well in the 1970. At that time the Society decided to discontinue doing professional research work for patrons.

During the late 1950s our friends, Frank Smith and David Gardner, as co-authors, published Volumes I and II of "Genealogical Research of England and Wales". Subsequently, in 1964, they published Volume III. These three volumes have been accepted as authorized text-books on English and Welsh research in genealogy both in and out of the Church.

To digress from research to a matter of personal history, let me insert here a brief statement of an interesting coincidence. We happened to be associated in a large furniture retail business during the 1950s and 60s. It so happened that my brother, Fred, and I had a high council associate on the stake high council, who was called to serve a mission to England. It so happened he became closely acquainted with a widower and two adult, but unmarried daughters, who were anxious to emigrate to America. In order to do so, it was required by law to locate an American sponsor, who would guarantee the American government that the immigrant would have steady employment. Upon return of our high council companion, we were asked if our business would agree to such a sponsorship.

The coincidence comes in the fact that our new employee was David Smith, none other than the father of Frank Smith, our English researcher. From this point on, our relationship with Frank became and has remained very close, indeed.

After Frank had served as our family researcher through the years of his being the Superintendent of Research for the Society, and patron research having been discontinued by the Society, Frank wrote us stating that he would like to continue handling our research which he could well do during his off hours from the Society. We didn't hesitate accepting his offer, for we realized there was no one better qualified. Too, from the fact that he had been handling it over the years, there was no one better acquainted with the research of our family.

Such has been the history of research for the John Wilkes organization. In 1976, Frank wrote a letter advising that the John Wilkes Family Organization had completed all that "could reasonably be expected of the family in research work." For reconfirmation of the above suggestion, I wrote a letter relative to the above decision, and in his reply, dated 27 September, 1982, said, "The Wilkes and associated lines should now rest for a few years until the Church has been able to microfilm more of the parish registers in their counties, and those parish records have been placed in the extraction program." The reader should remember that much of the research which was done, was by the English researcher who went directly to the parish vicar and obtained permission to search personally from the original records. Oft times the minister would limit the time for the research, as well at times, the years from which research could be done. Many of the parishes in our area have not been available to the Mormon Church to microfilm, due to the stubbornness of the minister. Often with the replacement of ministers, this situation may change and eventually the microfilming will be permitted, and will appear as part of the extraction program. Frank has advised us that every parish or record repository within a radius of twelve miles from any home parish of our ancestry has been visited and searched where access could be gotten. We have also been advised that some of the legal records of, particularly, Gloucestershire, such as wills, deeds, probates, etc., which may have been stored in Bristol and other large cities of the area, were destroyed by the German air force during the World War II bombings and are no longer in existence.

The suggestion that the family should remain aware of the fact that the extraction program of the Church is constantly bringing additional parish records. We should be alert to the possibility of additional parish registers coming available, which may make it possible for us to extend our pedigree chart. As of this writing, it has been approximately eight years since Frank Smith suggested that the family await new records. By 1900, and possible before, someone of the family should start reviewing what has been added to the extraction program of the three English counties involved, as well as Pembroke County in Wales. Certainly, it remains a family responsibility to continuously be alert to new research possibilities.

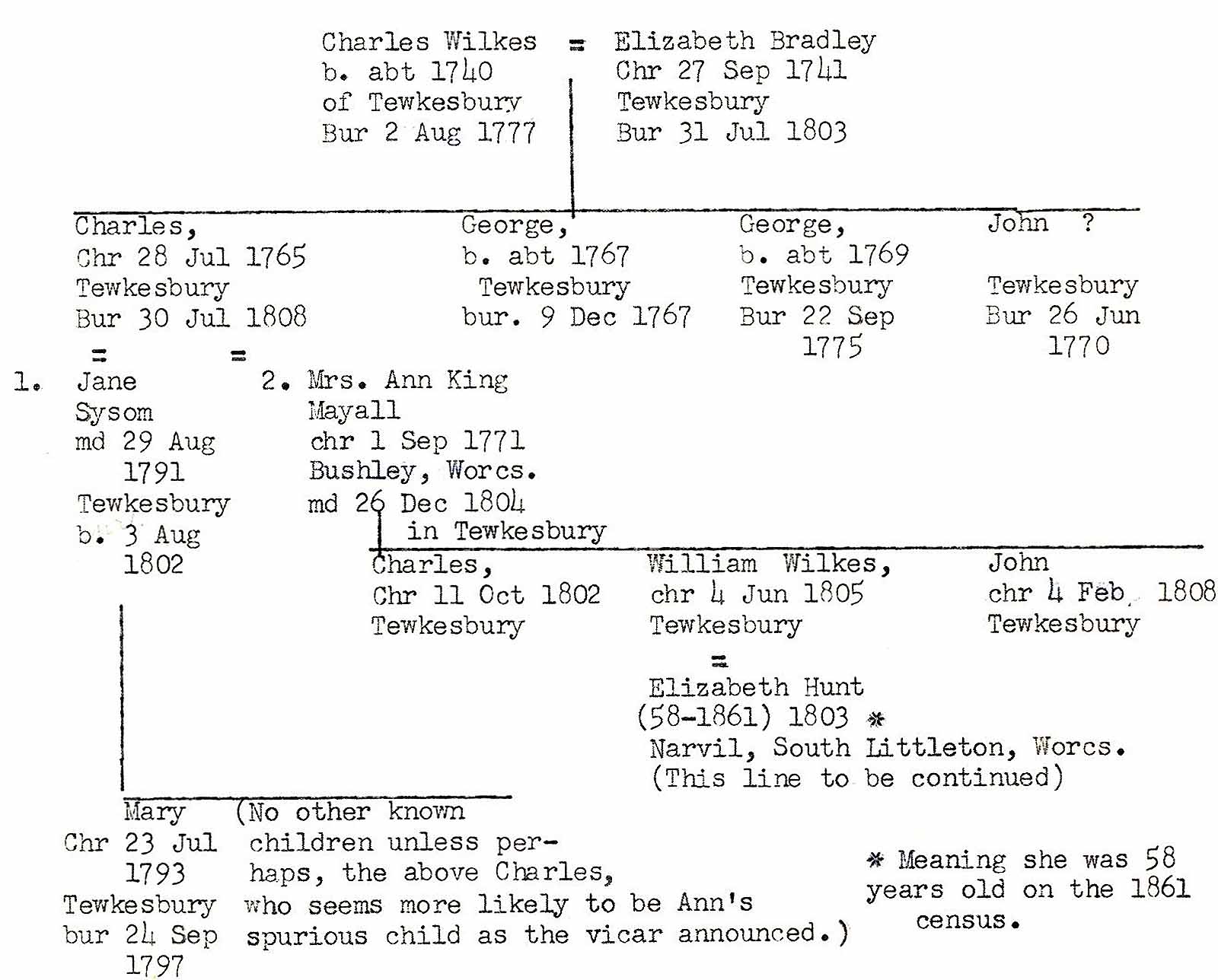

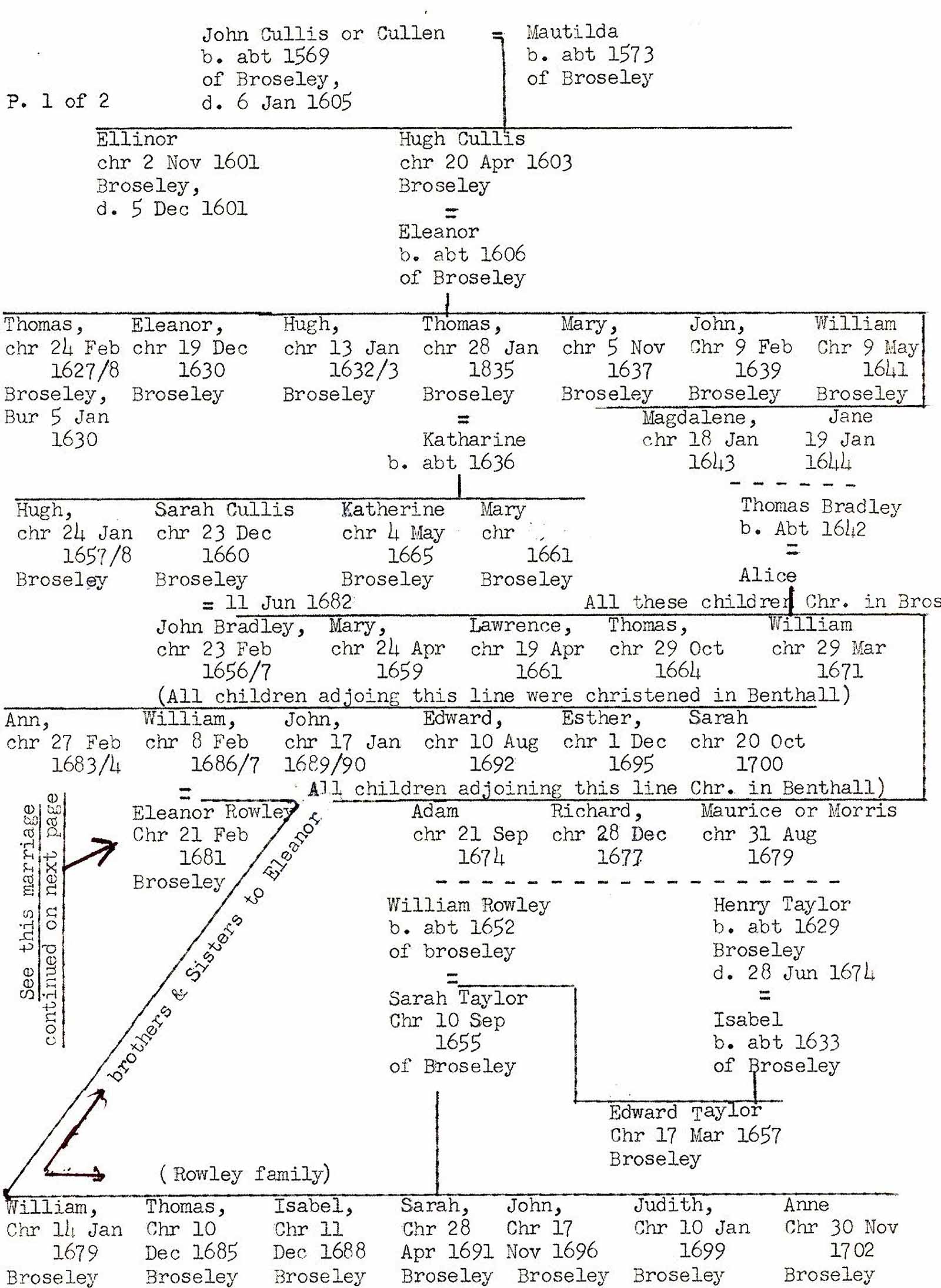

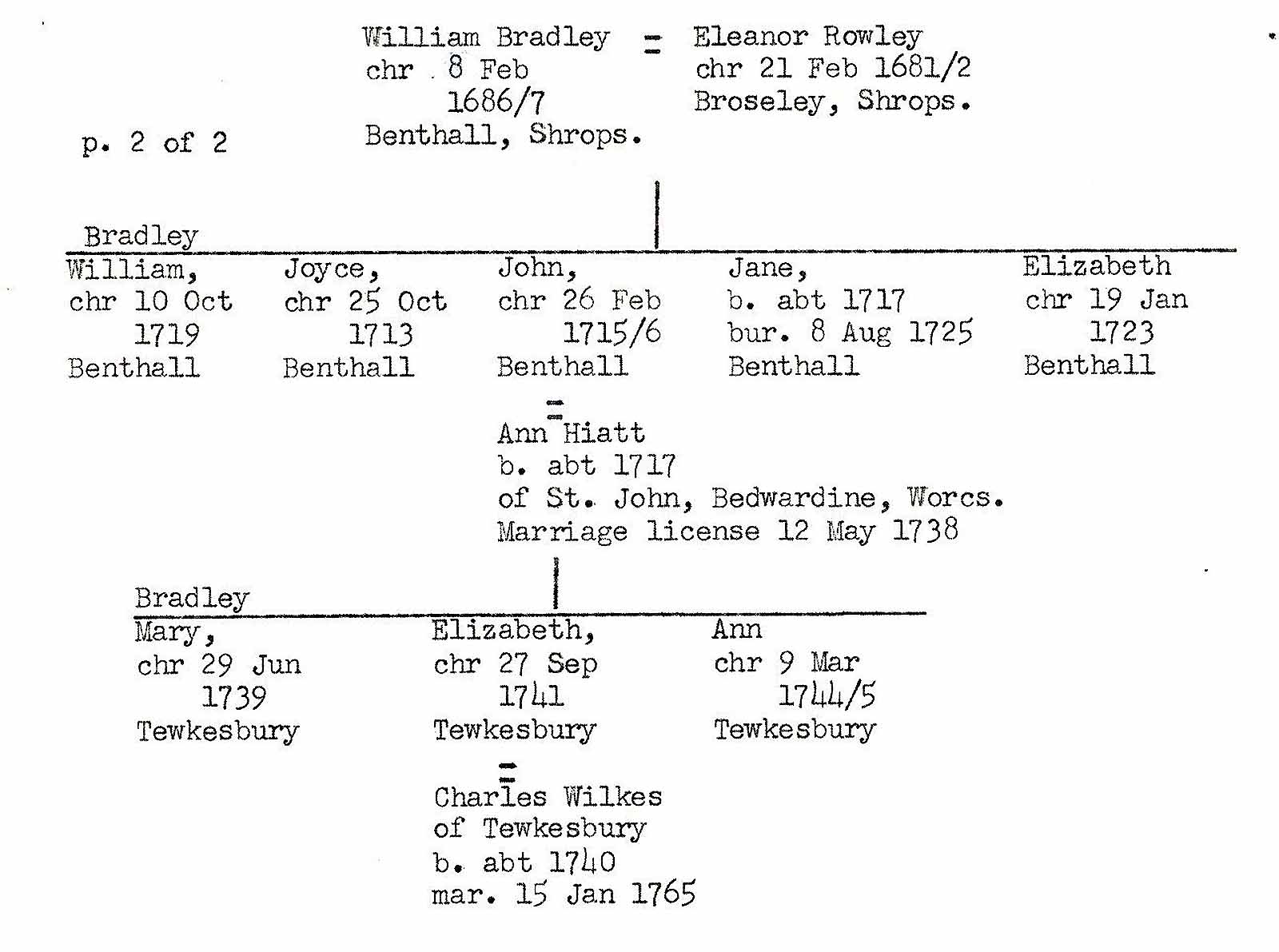

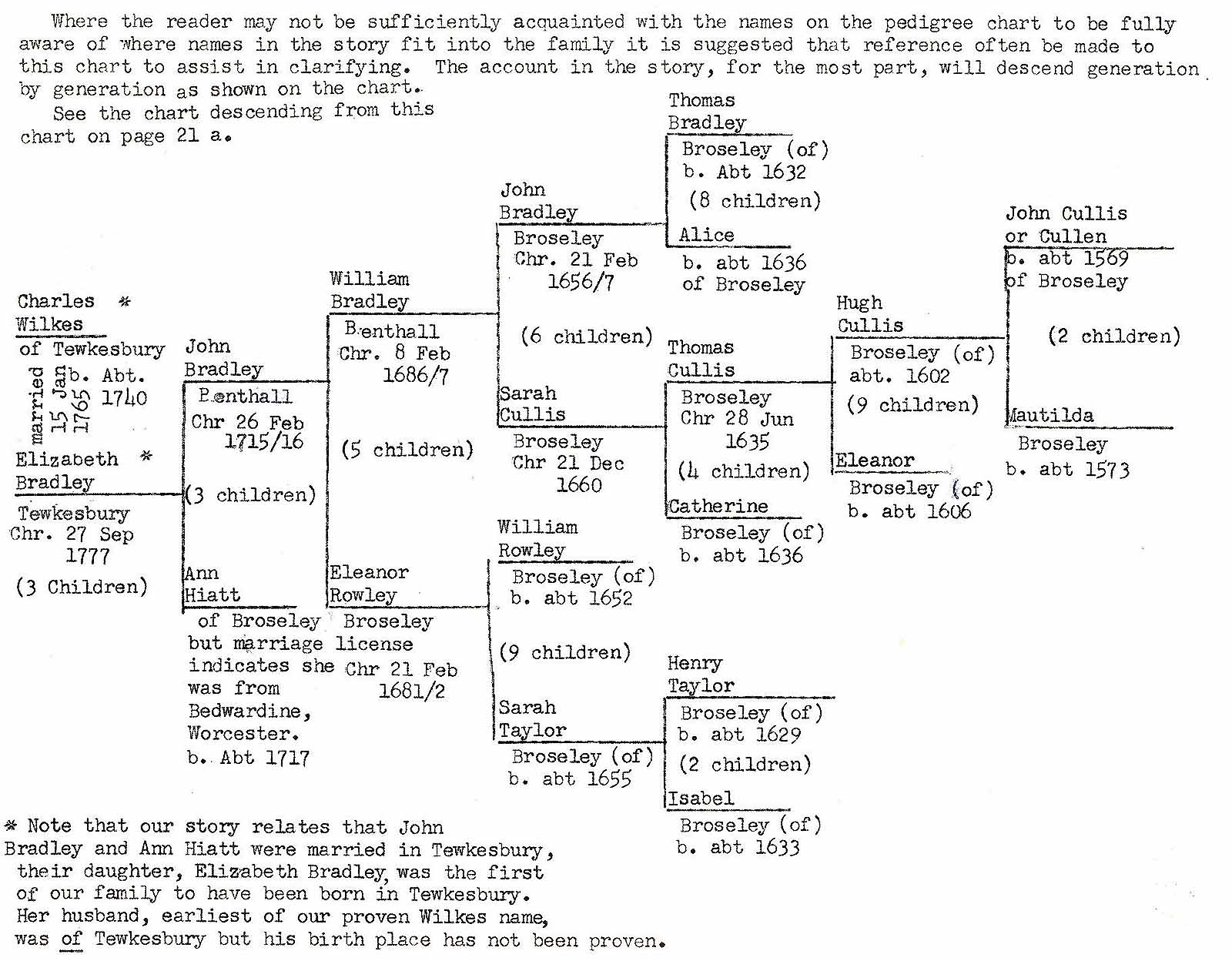

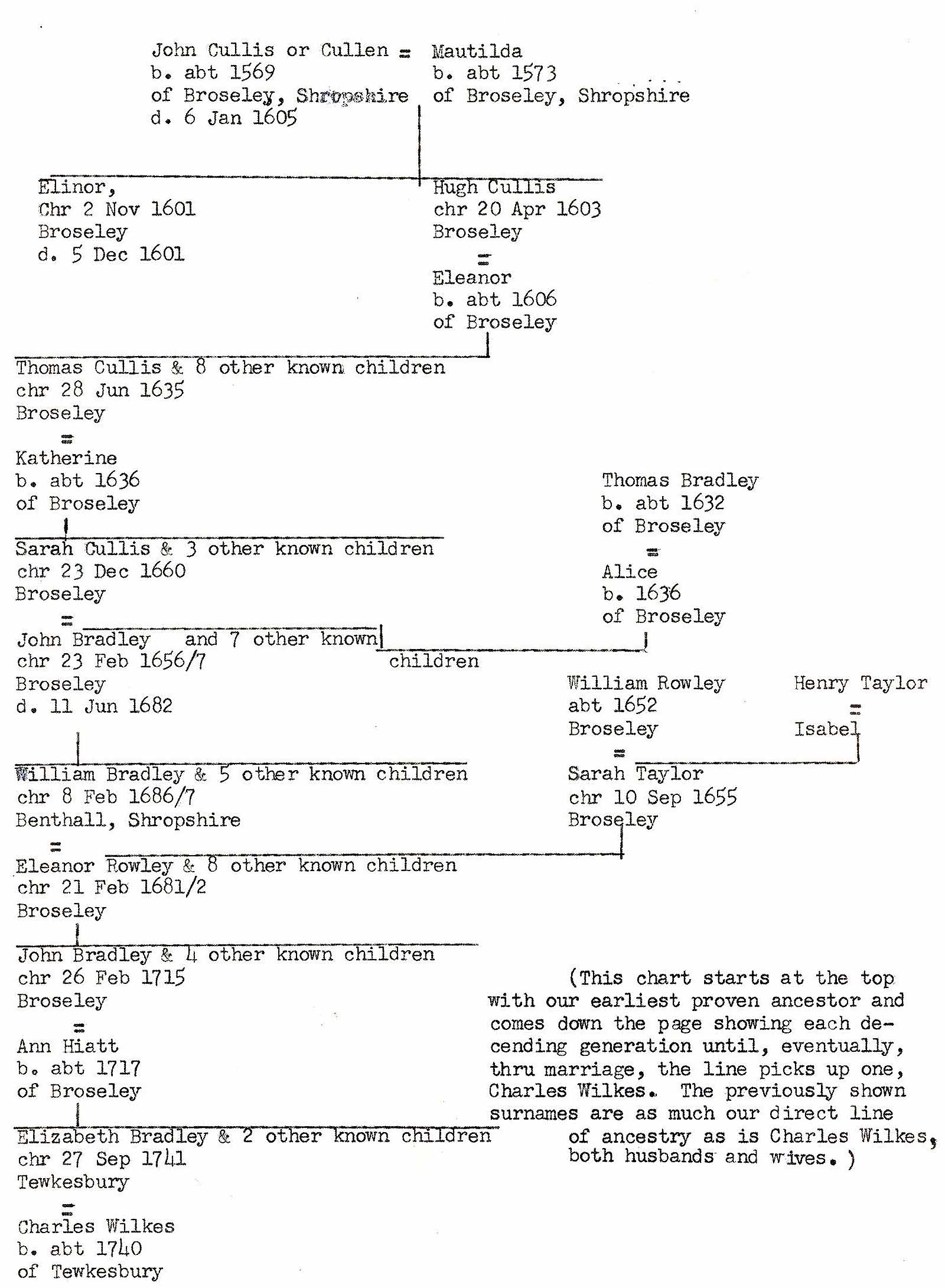

It is from the results of the past genealogical research that this history is being compiled. On the two charts will be found the last portion of the family's pedigree in two separate forms.

This chart is a simple profile with names and places only, to our earliest known ancestor. The chart commences with Charles Wilkes, the last known with the Wilkes' surname. As will be readily observed, he married Elizabeth Bradley 15 Jan, 1765, who's ancestry for six additional generations continue. We must remember that these ancestors, though by a different name, are as much a part of out ancestral family as were their name to be Wilkes. The genes of each of these ancestors contributed to each of us in proportion to the generation in which he or she appears.

This is a descending chart and has slightly more information than the one above. It is suggested they be closely reviewed.

As can readily be observed from the charts, our most remote ancestry is a couple, John Cullis or Cullen and his wife, Mautilda. No documentation as to either's place of birth has been found, nor do we know of the where or when of their marriage. The parish record tells us of his death, and that they had two children (at least) who were christened in 1601 and 1603 in Broseley, Shropshire, England. From these three facts relative to dates, and that what transpired was in Broseley, we can assume the parents lived in that town. Therefore, the phrase 'of Broseley' applies in these instances. The next several generations had their children christened in that parish and under such circumstances, it is proper to assume that that is where they were born.

With the locality now having been established as well as some dates - the children's christening in 1601 and 1603 - the very earliest of years in the 17th century (the 1600s) we can be assured the parents a reasonable number of years in the late 1500s. Now, to become acquainted with these ancestors, let us briefly look into the history of that period to become cognizant of their lifestyle and the conditions they faced.

Every school boy and girl of our generations was exposed to a degree of history. England, during the 1500s and 1600s, was the outstanding power of the world, and it was during this early period that the great and good queen, Elizabeth I, had just come to the end of her long and distinguished reign. In fact, she died in 1603. Her reign commenced in 1558, whereas it is estimated our earliest known ancestor, John Cullis, was born about 1569. He passed away just two years following the passing of the Queen.

Queen Elizabeth was the daughter of Henry the Eighth, who when his first wife was not able to provide him with an heir, he sought to divorce her. To do this, his request to the Pope was denied. This led to the king establishing the Church of England, with him at the head. To this day, the king or queen of England has retained leadership of that church. Queen Elizabeth was reported broadminded enough not to inquire too closely into the private religious opinions of her subjects, many of whom secretly remained loyal to the Catholic faith. She did require her subjects to attend the Church of England, and for each absence from attending the Sunday service, her subjects were fined a shilling.

This leads us to wonder as to the religious feelings of our ancestry, but in all probability, they 'went along with it' for shillings were hard to come by. The law also required that all christenings (baptisms), all marriages and all burials were to be taken care of in a Church of England parish, and it is from these very parishes, that the results of our research comes.

Interestingly, William Shakespeare, the great English dramatist and playwright, lived during the very years of our John and Mautilda, his life span being 1564-1616. Sir Walter Raleigh, a favorite of Queen Elizabeth, was contemporary with both the Queen and Shakespeare, and the two generations of our earliest known ancestry.

While on the subject of the royal family and government with whom and which our family had to do, let us drop down in years to John's grandson, through his son Hugh, to Thomas, christened in 1635. Thomas was the fourth of Hugh's family of nine children, and was fourteen years of age when the English monarchy was over-thrown. England remained without a king or queen for eleven years, the only years throughout the many years of English history. Queen Elizabeth's two successors did not fare so well as did she. Civil war eventually broke out, and a party of men of Parliament, known as the Roundheads, were led by one of their number, Oliver Cromwell. Their first intentions were to force King Charles I to allow them and his subjects to respect their respective rights. Charles did not feel as they did, with his insistence of The Divine Right of Kings. The king was placed on trial and was condemned and put to death in 1649.

For the next nine years, Oliver Cromwell directed the government under the title of Lord Protector. England benefited greatly under Cromwell's leadership. His sudden death, after nine years, brought the appointment of his son by parliament, but his brief two year administration failed miserably, and the previous king's son, Charles II was brought back from his exile on the continent, and proclaimed king, in 1660. This was the very year our direct ancestor, Sarah, the daughter of Thomas Cullis, who was mentioned a couple paragraphs earlier, was born. It was Sarah, who brought into our ancestral line the surname of Bradley, which became an important allied line.

Of the little we have uncovered of our family, we have no evidence that any of the men folk of these generations were required to participate in any of the political struggles. While such a possibility exists, it is not felt likely.

Nor are we aware of their occupations. In order for us to review the possibilities for their carrying on their own occupation, or of possible employment, let us briefly review a description of the area in which they lived. This can best be done by referring to an authoritative set of reference books known as Lewis' Topographical Dictionary, printed in 1833. It says,

"Broseley, a market-town and parish 4 miles east from Wenlock, 14 miles southeast from Shrewsbury and 144 miles northwest from London, on the road from Worcester to Shrewsbury, containing 4,299 inhabitants. Broseley has derived its importance from the numerous mines of coal and ironstone abounding in the neighborhood, which made it the resort of miners. The town is irregularly built, but is pleasantly situated on an eminence rising abruptly from the western bank of the river Severn, to which its eastern extremity extends, and from which its western extremity is nearly two miles distant. It consists principally of one long street from which a few smaller streets branch irregularly towards the different collieries and other works. The houses, in general built of brick and of mean appearance, are occasionally intermixed with some of more respectable character; and in detached situations are several handsome and spacious edifices. It is neither paved nor lighted, and the inhabitants are but scantily supplied with water, which in winter they bring from a well about half a mile eastward from the town and in summer from brooks at the distance of a mile and a half. The trade consists principally in mining operations; but from the exhausted state of the mines, it is rapidly declining. There are numerous coal-pits, iron foundries, and furnaces; and fine earthenware, tobacco pipes, bricks and tiles, are made to a great extent. The fire-bricks for building furnaces are in great repute, and by means of the river Severn, are sent to various parts of the kingdom."

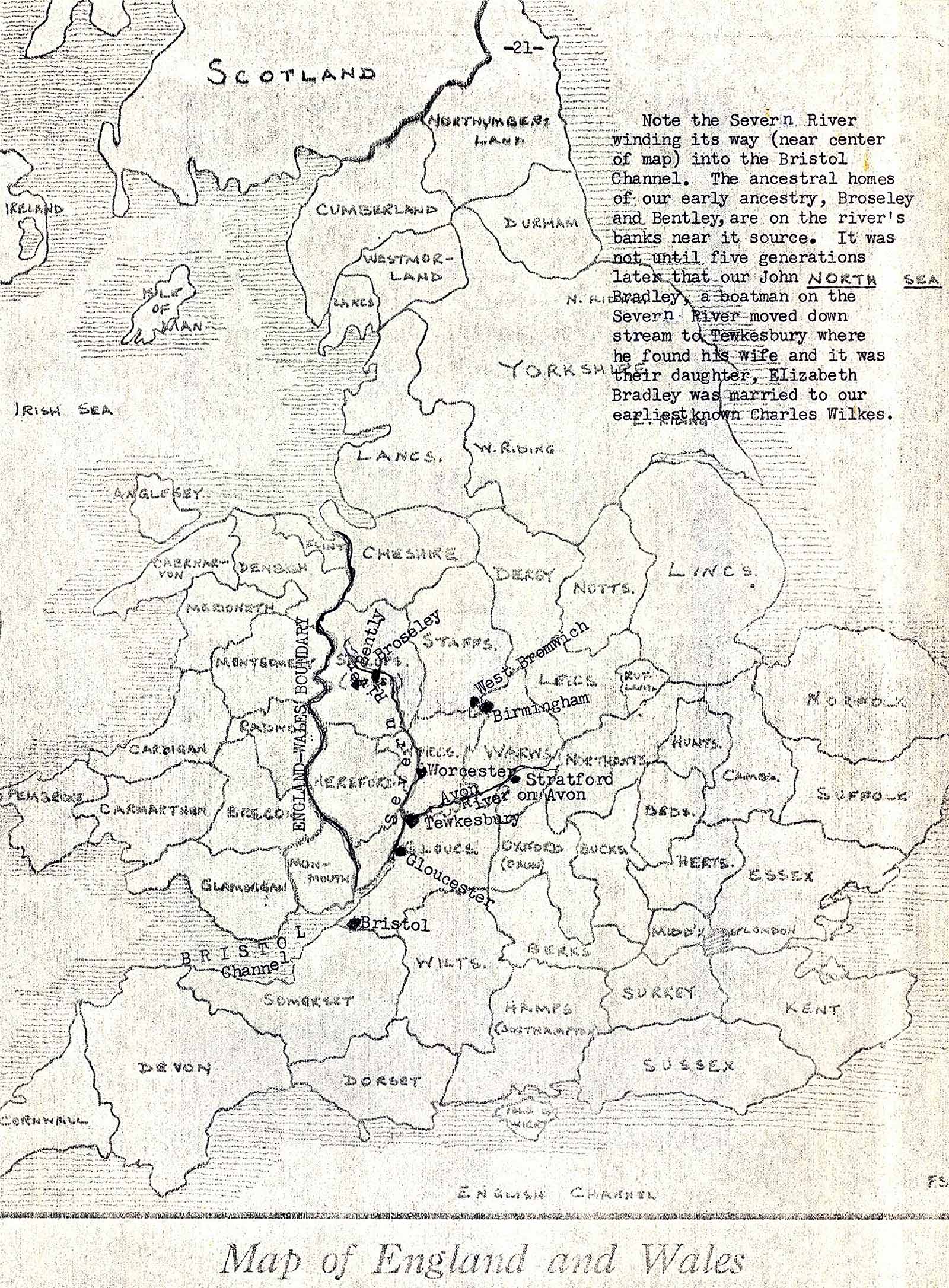

By glancing at a map one sees Broseley slightly to the south and east of the middle of Shropshire, which is on the western border of the midlands of England and bordering Wales. Today (1984) Shropshire is on the outskirts to the west of the most heavily populated area of England, excepting London itself. The counties bordering Wales - as Wales itself - is considerably less heavily populated than most of the rest of England with the possible exception of southwestern England - Somerset, Devon and Cornwall - and the extreme north of England adjoining Scotland, which area is quite hilly.

See a map showing the Wilkes places area here.

Now, as to Broseley itself: In 1833, it had a population of well over 4,000 people. By England's population standards, this is not a populous center, yet, 200 years prior to that time - in 1650 - it was not a country village either. Its population then would have been smaller than in 1833.

From the description, one can let his imagination lead to the possibilities for the kinds of work the area offered. First, let us consider the fact that Broseley was a market town. Every town was not a market town and where there was as much mining and manufacturing of iron and clay products as there was reported to have been at that time, we can be assured there would have been considerable activity at the market. Our families of this period, nor other families ever dreamed of the day of refrigeration such as we enjoy today. Fresh food was a necessity, and this created an almost daily market. Actually, market days in England, even today, are held at least two if not three days a week, and these days represent a lot of activity. Foodstuffs of all descriptions are brought to the market by merchants, and particularly farmers. Even live animals are included, but often farmers butcher their animals the evening before and bring their fresh beef, mutton, pork, chicken, ducks and geese. Flies in that country are not as bad as here, but there were flies to contend with. Fresh vegetables were usually in abundance and were sought after by the townspeople. Prior to modern-day transportation, getting fresh fish to inland towns was a challenge, but a little of it was brought, but the cured or salted fish were a merchandise item. Naturally, all types of woven goods from blankets to stockings were piled on the market-day tables for customers to 'wade' through in search of the right priced and right sized items. Many people are occupied in a market town, and we are at liberty to wonder if members of our own families had any significant roles to play. Were some of them farmers with a few acres within an hour or two hours traveling distance? If so, with their single horse and heavy two-wheeled cart they would have to start from home before daylight for the market place. Perhaps it was a light-weight two-wheeled cart which was pushed manually by members of the family.

Other than market days on which to deliver home grown produce, there were those farmers who had regular routes through the residential districts, and for whom the housewives were waiting for such needed foodstuffs as a loaf of break, a quart or two of milk, a week's supply of turnips, a head of cabbage, a handful of brussel sprouts or a heavy burlap sack of coal. Any or all, or many other such activities, required people who did this work as a means to provide themselves and families with a living. Our families may have been sustained in this manner. We don't know.

On the other hand, with so many coal mines having been reported, it is very possible that it was to these coal pits the men folk entered for a ten or twelve hour daily work shift. Except on Sundays - and particularly during the winter months, they never saw daylight. Extracting coal from the coal seams far underground was a slow, dangerous process, with all the work being done by pick and shovel during these early years which we are considering. There was work down these mines even for small children. Some coal seams were so small that a man could not get into them to get the coal out, and the children six and eight years of age were able to crawl into them and throw the coal out to where an adult could shovel it up into a coal cart which rolled on iron tracks to the mouth of the mine. Where these was room in the mine for a pony, mule or horse, they were hitched to the coal cart, but back in the shallower tunnels of the mine, the miners provided the horse-power. Often women put on a harness and pulled the carts, and in some areas due to lack of space, had to get down on hands and knees to do so.

At a much later time, James Watt invented the steam engine in 1769. Eventually an engine was placed at the top of the mine with a long rope or cable attached to the coal car down in the mine, to pull it to the surface. This became a great boon to the effort of getting the coal out of the mine.

After the coal reached the top, there remained much hard work. It had to be delivered to its destination to be of any value. Before the time of steam engines, our pedigree chart shows we had at least seven full generations of proven ancestry prior to James Watt, the coal had to be moved manually, unless the tipple was in such a position that the coal could be dumped directly into carts of wagons. Possible, here at Broseley, it could be dropped directly into the barge or boat which plied the Severn River, for as we shall see later, parts of this river were navigable.

There was much work to be done in Broseley. The making of fire-brick for the iron ore furnaces, regular building brick, high quality earthenware, the mining or iron ore and even the manufacturing of the tobacco smoking pipes, required laborers of many descriptions. Of course, the exporting of these items to other towns became essential. These were but a few possibilities for our families to have been employed.

We must not overlook the fact that it is very possible our ancestry were involved in what we term today as the blue-collared or even white collared strata of society such as the owners, the managers, merchants or office workers. Over these seven generations with whom we are directing our attention for the present, see pages 6 and 7, it is very possible there could have been a sprinkling of these people in most of the activities of the community, from the hard working laborer, to the position of management and even ownership. Just as today, we can examine the generation now in the prime of life, the production generation, we can find many, many facets of occupations. Similarly there is the same possibility between 1600 and 1899, the two hundred year span represented by the charts.

It must be kept in mind, however, that in whatever type of work they were involved, there was hardship. During these generations of which we are considering, it is hardly probably that many, if any, were able to read and write. Such a situation was quite common even down into the middle of the 1800s, and we are keeping in mind that some of these people were as far earlier than the last of them, as George Washington was earlier than our day.

Quoting from Frank Smith's "The Lives and Times of our English Ancestors",

"Laborers lived at a very low subsistence level as the prices had increased six times in the last two centuries, whereas wages had only doubled. For example, the average laborer fed his family on porridge, watered-down milk, and bread made from barley and rye. Bread made from wheat was a luxury only within the means of wealthier families.

Turnips, carrots, cabbages and the potato, which was of New World origin, was only slowly gaining in popularity. Sugar, now being cultivated in the West Indies was beginning to take the place of honey.

"Some fish was eaten, but if it had to be transported inland, it had to be heavily salted for the sake of preservation.

"Pears, plums, apples, and cherries were grown, and more attention was being paid to manuring the ground. This, with the introduction of the turnip, the potato and clover, was to revolutionize agriculture in the next century." pp. 123

Quoting from elsewhere in "The Lives and Times of Our English Ancestors",

"In this century (1600-1700) the local grocer and general dealer began to carry goods on his cart to housewives. This was a great boon to all concerned as the roads were still very bad, and the practice has continued until this day.

In the first half of this century there were at least seven hundred miles of navigable rivers which were used in the transportation of goods and passengers. By the end of the century another thousand miles had been made navigable." pp 141

Times and conditions changed during these two centuries, particularly so in the 1700s. Enterprising merchants and small businesses related to manufacturing of a multitude of items, particularly in the clothing line, 'farmed' out to the villagers 'piece work' which was done in the homes. The industrial revolution during these early years had not come into its own. Large factories had not come into being, so the merchant needing sweaters had to have them hand made. First, weavers had to make the cloth on hand looms in people's homes. The merchants would then distribute the cloth to other homes for the making of clothing of all types. Yarns were furnished to housewives by these enterprising merchants, and sweaters and other knitted pieces were made, often after the waking hours of the children. Hides were gathered from the farmers who had butchered their animals, and taken to other homes, whose men folk had learned to tan and otherwise prepare the hides into leather. The merchant could then take the leather to still other homes that had a small room where a certain number of pairs of shoes could be made by the man of the house, to be picked up by the merchant at the end of the specified time, say the end of the week. Thus, his customer's family, probably the family who wove the cloth, would have shoes to wear to play in the yard, or a miner's family could be provided with shoes in which to spend the ten or twelve hours a day in the dingy and unsafe mines.

And so, the living, or perhaps just the existing process, went on from year to year, from generation to generation, with mainly each community providing for itself.

As the years passed, inter-community interchanges were found to be practical. A successful merchant-manufacturer found he could oversee the weaving of more cloth than the people of his community could use, so he envisioned taking his excess cloth to a neighboring community and perhaps, trading it for more leather, or pottery or whatnot. This opened the need for a means of transportation, which led to the need for carts or heavier wagons, which led to the widening of footpaths into roads, which required cobble stones, etc., etc. It was early discovered that carrying freight on the rivers was simpler and more profitable than building roads, so wherever feasible, barges were built and floated down the rivers with their cargo. Spots in the rivers had to be widened or deepened to permit larger barges. After the barge reached its destination, means had to be found to return it to its place of origin, so a horse on each side of the river, hitched to a long rope, pulled the barge upstream. If the flow of the river was too slow, this same means was used to assist the barge to go downstream. Pulling by one horse only, from one side of the river, invariably pulled the boat into the bank, so it required a horse on each side, to keep the barge in the center of the stream. It was soon learned that by the use of a steering apparatus on the barge known as a rudder, the barge could be held to the center with but one horse pulling from one side.

Water traffic on the rivers proved so practical, that canals were resorted to, and so expanded the means of interchanging products from one locality to another, all of which provided employment.

As stated earlier, it was yet another hundred years before the steam engine, which led to the end of the domestic system of home manufacturing. This and other inventions were often not willingly accepted. The fact that one engine could do the work of dozens of people was, at first, reluctantly accepted. Unemployment became a scare first, and then a reality. The merchant who was successful in having his weaving done by hand in the home of one of our Cullis, Bradley, or Rowley families in Broseley, joined with others of his trade and built a large factory to be powered by steam engines. The new processes far exceeded the output of the single small spinning-wheel of our ancestor's homes.

A real problem, and unquestionably a problem which caused many of out ancient family to lay awake at night worrying, was the fact that the new factory was not to be built in Broseley. In all probability, it was to be built as far away as southern Lancashire, some seventy miles to the north of Broseley. It their interest had been in hides and leather, a factory was to be built in Northamptonshire, about the same distance from Broseley to the east.

We don't fully know how catastrophic this great transformation caused by the Industrial Revolution upset our family, but most likely, it eventually became necessary for some of the families to move to other areas where there would be ample employment in the new factories.

As has been mentioned, Broseley was noted for its coal mines, and the first thought of our family could have seen a possibility of their mines producing the coal to power these large factories. Steam engines would require coal, but Lancashire, as well as Northampton, were actually sitting on coal beds, and the transfer of coal from Broseley would not be necessary.

Broseley was fortunate in that beds of ironstone were near the ground's surface, and this iron ore was processed in furnaces heated by local coal, so Broseley continued much as it had for centuries, excepting for its 'home industries' as explained.

We want to keep in mind that Broseley, our ancestral home for generations, was located on the banks of the Severn River, which was used quite extensively for transport purposes, so while far inland, the boat and barge freight business played an important part in the economy of the community.

From our early research, we find our earliest located generation, John Cullis or Cullin, and his wife Mautilda, had their children in Broseley. The next generation coming this way, Hugh and Eleanor, also had their nine known children in Broseley. Continuing this way, the next generation, Thomas Cullis and wife, Catherine, had their children all christened in Broseley, but the next generation this way, makes a change in that their daughter, Sarah Cullis, marries a young man, John Bradley. He was also christened in Broseley, but married on the 11th of June, 1682 in Benthall, a small parish only three miles west of Broseley. While in 1833, Broseley was listed as having a population of 4,299 residents, Benthall at the time had 525 residents. Interestingly, the Benthall parish is the older of the two parishes, despite it remaining so much smaller. Its registers were commenced in 1558, while the registers of Broseley commenced in 1570. Undoubtedly, the fact that Broseley is located on the banks of the Severn River, and has river traffic, has given it an advantage over Benthall so far as the greater population is concerned.

This John Bradley and wife, Sarah Cullis, had their six children christened in Benthall, as did their son, William, after marrying Eleanor Rowley. Eleanor had been christened in Broseley, but had their children christened in Benthall. We are but taking license here to assume they lived, as did William's parents, in Benthall, on the strength that their children were christened in the smaller town. While this would assume to be logical, there may have been circumstances of which we are not aware to have made it otherwise.

Among the children of the latter couple, William Bradley and Eleanor Rowley which number five - two boys and three daughters - was their third child, a namesake for his grandfather, another John Bradley. He was, as stated, christened in Benthall, as was his brother and sisters. His is an interesting story, but before it is related, let me, the writer, reminder you, the reader, that his history is being written in reverse to what our original research was undertaken. Let me explain: Our present files show that we were making the searches for these families, and were locating this generating back in the 1950s. In that researching, we were following the normal procedure to go from the known to the unknown, therefore, we were going back in the search of the ancestry of my grandfather, John Wilkes. We had already reached John Wilkes' 2nd great-grandfather, one Charles Wilkes, who had married an Elizabeth Bradley on the 15th of January, 1765, in Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, and we subsequently located the christening of their three known children in that parish.

In an effort to now extend the Bradley line, we also found that Elizabeth Bradley had been christened in Tewkesbury, on the 27th of September, 1741, and from these same records, found two other sisters, an older one, Mary, who was christened on the 29th of June, 1739, and a younger sister, Ann, christened 9 March 1744/5. From this record, the girls' parents were found, the father, John Bradley and the mother's name Ann.

Keep in mind, we did not have the information we now have in this history. We were going from the known into the unknown. We found the Bradley line and learned that the girl's father, John Bradley, was christened in Benthall, Shropshire., but what about Ann?

The research was proceeding much slower than the reading of this history. To get to this point, it had already required years by slow correspondence, at that time by boat, or what we called surface mail.

The marriage of John Bradley had to be located, at least it was desirable. More than thirty parishes were then searched in the area of Tewkesbury, all to no avail so far as marriages were concerned. In as much as Tewkesbury is situated close to the county boundary line between Gloucestershire and Worcestershire, parishes in both shires were searched.

There were two alternatives in the process of preparing to be married. First, the applicants who wished to be married were required to declare a banns with the ministers of the parishes to which they belonged. These banns were to be read publicly in each parish service for three consecutive Sundays. The parishioners could then protest should they know of any reason the proposed marriage would not be legitimate. Secondly, should those applying to be married prefer to not have their names read publicly for any reason, or if they preferred not to have to wait for three Sundays to pass, a license could be purchased from the bishop of the diocese. (In the LDS Church, this would be comparable to a stake president, rather than a Mormon bishop). Not only would the parties have to be able to afford the price of the license, but they would have to bond themselves with a specified amount of money to allege that there were no known reasons why they should not be permitted to be married.

Naturally, the latter record, known as 'bonds and allegations', were not in the records of the parish, but rather in the diocese, and it was to this source that our researcher eventually went. This marriage between John Bradley and Ann, was of sufficient interest to the then Superintendent of Research of the Genealogical Society, Frank Smith. In his second volume of "The Lives and Times of Our English Ancestors", he wrote of this incident under the title, "Population Movements in England and Wales by Canal and Navigable Rivers", pp. 185. Here is the quote as he prepared it:

"John and Ann Bradley had children christened in Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, as early as 1739. Their marriage was not found in this parish, and because of this the search was extended to the surrounding parishes. Thirty parishes were searched without success before a decision was made to search the marriage bonds and allegations for the diocese of Worcester (Tewkesbury is in Gloucestershire, but near to the border of Worcestershire).

"A marriage bond with allegation relating to the above couple was found indicating that they were married at St. John Bedwardine, in the city of Worcestershire by license on 12 May 1738. Additional information showed that Ann's maiden surname was Hiatt, that John Bradley was a waterman of Benthall, Shropshire, and a witness to the marriage was a John Harrison, a waterman of Tewkesbury."

Despite the fact that the bond and allegation form was completed and the license issued, the actual marriage record has never been located for the simple fact that the entire marriage record for 1738 is missing from the Bedwardine Bishop's Transcripts. This loss of record is most regrettable, because it stops further research on the Ann Hiatt line of ancestry. There appears every evidence that the marriage transpired, for we even have the record of the children, but there is no record of the marriage itself.

An interesting story can be re-created of this supposed marriage. The Severn River spans the distance between Broseley and Tewkesbury, and is navigable. Probably, John Bradley traversed back and forth with a boat or barge, hauling freight from Broseley to Tewkesbury, if not further, a distance of forty-five to fifty miles by air, further by river. In his day, his only source for power to pull his barge or boat, would have been a horse. He would have had to wait another nearly thirty years for James Watt to invent his steam engine. That engine eventually powered larger boats and ships. Whether such engines ever became practical for barges or canal boats may be questionable, for even at the time of this writer's first visit to England in 1928-30, horses were still being used on canals.

But back to the trips John made. In the allegation, he was mentioned as a 'waterman' of Benthall, and his friend, John Harrison, a 'waterman' of Tewkesbury. Could it have been only on occasion these two men met as they each plied the river? Was Tewkesbury the meeting place, where on occasions they could spend an evening together visiting and telling each other of their experiences? We can see these two acquaintances walking the streets or, perhaps, stepping into a well-known pub for an hour's social relaxation. All this is quite possible, and perhaps, the fact that Tewkesbury was the home of John's friend, he was most likely the one who introduced him to his upcoming wife-to-be.

As a result of his marriage to a girl whose home (their marriage place could indicate that to be her home) was within five or six miles of Tewkesbury, one can suspect why he permanently moved to the Tewkesbury area.

To give us a little clearer perspective as to the time we are now in with our family story, we can relate the time of the marriage of this couple to the cherry tree incident of the Father of our country, George Washington, for he, George, would have been about the age of six, when John and Ann were married. From our present time of 1984, John and Ann were still quite a long time ago, despite the fact that our story began five full generations prior to their time.

Now, with John Bradley and Ann Hiatt now living in Tewkesbury, the parish records of that place reveal to us the christenings of three daughters, Mary, Elizabeth and Ann, as before stated. Elizabeth, the second daughter, became our direct ancestor by marrying, on the 15th of January 1765, our Charles Wilkes, with whom we shall commence a new chapter.