MY MOTHER

By Mabel Brown Blacker

Mabel Alice Godber

Mabel Alice Godber

It was March 27, 1882. Even if it had been a nice, sunny day, the occasion was a sad and somber one. Alice Hames Godber, a young woman of thirty-five, was carried into the cemetery of the South Normanton church. Often during the fourteen years of her married life, had she come to this place, as time after time, she lay to rest her lovely babies. This day she came to sleep beside them. All were here except her baby, a little girl, not quite two years old, who stood by in wide-eyed wonderment, as she watched the casket containing her mother being slowly lowered into the grave.

Who knows the emotions of a child on such an occasion? Certainly this child never was able to recall. I imagine she was lonely and afraid, for she was alone. Mother was to be no longer with her, and in all the confusion and excitement, her mother was needed and surely wanted. One thing must be sure, and that is that the heartbreak, the hurt, and the longing loneliness were not experienced at that time. Those emotions were for the days and the years ahead, for the days when a mother would be needed, but was not to be there. She was so young that all recollections of her mother slowly left her. She was not to have even the memory of her mother's loving face and sweet smile to comfort, to give solace, and to fortify her for the trials and hardships of the years that lay ahead. Not even a picture was to be hers to treasure.

This little girl was the only one left in her home. Always for her, there had been a big brother, Arthur, to play with and to help take care of her. A few short months before, he had died, and now Mother, too, had left. Father? She couldn't even remember him. He had gone far away to the United States to prepare for a home for his family, a home his wife and son would never need.

The little girl, Mabel Alice Godber, had been born in South Normanton, Derbyshire, England on the 11th of August, 1880, the last of the seven children of James and Alice Hames Godber, and the only one who was to live longer than nine years.

No doubt, the father, when he returned to England, wondered why he had been left with a little girl. Why had not his son, Arthur, lived, he would have known how to care for a boy - but a girl - and so young - and he was a stranger to her.

The font in the Saint Michael and All Angels Church in South Normanton where

Mabel Alice Godber was christened.

The font in the Saint Michael and All Angels Church in South Normanton where

Mabel Alice Godber was christened.

Had James Godber been blessed with a vision at this time, he would have seen that his baby daughter had an important mission on the earth; and he was to play a part to help her fulfill it. The mission was not to be performed in the little English villages and towns, where her ancestors had lived for generations, but in a new land, far across an ocean, and almost all the way across another continent, to a land of snow-capped mountains. It would be an unassuming, quiet mission, but one that would require courage, strength and fortitude. The nature of the mission would be such that it would affect the lives of many people, many dead, many yet unborn, and among people in many lands.

Before her death, Alice Hames had dreamed of owning land, and of having a home in America. This dream had meant so much to her, that she had sent her husband to America to prepare for it. He had also had the dream and wanted freedom from the traditions of his native land. For a few years after his return to England, the father and his daughter continued to live there, but the dream would not die. Finally, he decided that somehow, somewhere in America, he would make his dream come true. His parents were dead. His brother, William and wife, Sarah, were already in America, in Pekin, Illinois. As the plans and preparations were being made, a younger and unmarried brother, Isaac, decided to go with them. It was goodbye to England forever, for all three. Never again, would their feet touch the soil of their native land. (In December 2009 we found a record of the voyage on the ship Celtic. Ruth Blacker Waite)

I fancy I can see them standing on the deck of the ship, watching through tear-filled eyes as the shores of their beloved homeland slowly faded away in the distance. All that was dear, and home, was behind them, but the father would always carry with him the memories of his loved ones sleeping in the little churchyard, and with whom he was leaving a part of his heart. Many times in the years ahead would he sit and dream of his life in England, with family and friends and the warmness of sweet memories would mellow the trials of life.

This voyage, perhaps, was a thrilling experience to a little girl of about four and one half years. She didn't -- she couldn't-realize all she was leaving behind, and it was fun to watch the waves of the ocean, and to be on a ship.

As the years went by, she recalled only a little of life in England. She claimed that she had attended a type of nursery school and that she remembered that she had to pass a big dog on the way, of which she was dreadfully afraid. She recalled some pretty dresses she had and a hat with a feather in it. A smallpox vaccination with which she had trouble, and she remembered a little of her trip across the ocean, during which her father had become so dreadfully seasick.

At last the voyage was over, and as they watched the shores of the new land get closer and closer, the father realized that somewhere out there he would make a new home, and with the help of the Lord, find the peace and freedom he was seeking. Somewhere out there would his dreams come true? This was in 1885.

I wish I had asked more about where they went when they arrived in America. Why didn't they go to Illinois to see his brother, William and wife, or why did they go to Colorado - where, I don't know. He had been in Indiana the first time, but for some reason, he chose not to go there to live. The reason for their leaving Colorado to go to Rock Springs, Wyoming is likewise unknown. This I believe: The Lord was guiding them to the place where the girl's mission was to be performed.

Rock Springs was a typical mining and railroad town of the early west. Wyoming was still a territory, and would be until 1890. I can easily imagine that to these home-seeking travelers, this place would seem to be the end of the world. This dry, dusty town surrounded by barren, rocky hills was so unlike the pretty, green villages of England. And the wind was almost forever blowing!

But the past was behind them. There was nothing to do but find employment in the coal mines and to start anew. This they did. They rented a company house (the mine owners built houses which they leased to their employees) bought what furniture they needed and started a new life in a new land.

William Godber brother to James

William Godber brother to James

William and Sarah Godber with William's grandson on the left.

William and Sarah Godber with William's grandson on the left.

There is certainty that they were in the United States in 1885, for I have a letter from his brother, William in Pekin, Illinois, in answer to one Grandfather had written to him, telling of their arrival in the United States. William had been concerned as to their whereabouts. He wrote, "I have been thinking no doubt you had gone down to the bottom of the ocean." He also told him to write to his brother, Harry (Henry), in England, for he had not yet heard of their safe arrival to this country.

For a surety, they were in Rock Springs in September of 1885, because that was the year of the "China Racket". Rock Springs was a very cosmopolitan town. People had come there from nearly every country in search of homes, opportunity, adventure or what have you. Many Chinese had come to America, mostly men in search of employment. They had helped build the railroad - the Union Pacific - and when that was completed, they had obtained work in the coalmines. The Chinese lived together in cheaply put-together houses. Their wants were few, for they had no families with them, and so they could live more cheaply than the white workers. The Chinese refused to join the unions and would not strike against the owners of the mines. Conditions became so bad, that on the 2nd of September 1885, the white workers "blew up" the homes of the Chinese! The United States government sent the army to restore order and to protect the Chinese from actions brought on due to the ill feelings of the whites. As earlier mentioned, Wyoming was still a territory, and this trouble became an international affair. War was averted, but reportedly, it cost the US government $147,000. Twenty-eight Chinese were killed, and fifteen were wounded. These events had a lasting impression on the little girl from England, and she often told the story to her children. She told of how frightened she became at the noise of the explosions and the dust and smoke as the homes went flying up into the air. The Chinese, with their long ques, came running out of their homes, and escaped into the hills in fear, but all were brought back by the soldiers and taken care of until the government took them from Rock Springs.

The then desolate and forbidding region of Rock Springs was not to be the final home in America of Grandfather and Mother. The Lord knew this was not the place the mission was to be performed. They heard that Almy, some sixty or more miles to the west was a better place in which to live, and that work in the coalmines was available. This next move was made after having lived in Rock Springs for about eighteen months. Again these strangers pursued their search for a permanent home.

We are not aware of the month they moved to Almy. Someday we may be able to determine from records we have not yet located. The little family was determined to stay in America despite the fact that life may have seemed difficult and lonely, and their dream far away. The records of the Uinta County Third Judicial Court in the clerk's office at the Court House in Evanston have revealed the following item of historical note" "Declaration of intentions of James Godber to become a citizen of the United States". It was dated 2nd November 1886 and was found in Book B on page 66. The move to Almy, therefore, was sometime between the date given of them as of the 2nd of September 1885 and the date of the above application in Evanston, 2nd of November 1886.

Remains of one of the mines near Almy

Remains of one of the mines near Almy

Sometime during the years they lived in Almy, Grandfather either bought or leased a small acreage down below the hill from Mine #3. It was here at this home that they joined in the community life, with daughter, Mabel, attending school and other activities, which the community offered. Almy was, in the main, a Mormon community, but other churches were also there, and the Godbers were not Mormons, so they attended mostly the Methodist and other Protestant churches, either in Almy or in the railroad town of Evanston, some three miles to the south of their home. It is not known whether Grandfather ever became interested in the Latter-day Saints, but he allowed his daughter to attend their meetings with her friends. She often said he would ask her if they, the Mormons, read out of the Bible and she would say that it sounded like it. In as much as I never knew my grandfather, I can't say how religious he was, but I have heard that he often asked his friends to kneel and pray in his home. As my mother attended the meetings of the Mormons, she was surprised that so many "ministers" sat on the stand.

Soon after their arrival in Almy, Grandfather purchased a team of horses, which was the pride and joy of both of them. You can be assured the horses were well taken care of. Although Grandfather lived near Number Three mine, he worked at other mines, so he used the horses to travel back and forth. As Mother grew older, her father bought her a small horse to ride, and she would take him out to pasture. One day, as she was leading the horse with a long rope to a place where she was to "stake" him out, the horse became frightened and started to run away. She decided to let go of the rope, but she got her foot caught in it and was nearly dragged to death. Fortunately, the rope broke and her life was spared. The hard part of the affair was that the pony was sold, which her father said was necessary "before she was killed."

Mother had a lot of black hair and she always said her hair had saved her life. She did say it took her father and her a long time to get the dirt and pieces of brush and what-not out of her hair. Washing her hair was always a major job for her father.

So they lived, worked in the mines, and their life was, I suspect, to an extent, happy. Uncle Ike (Isaac) lived with them, for he never married. However, he would always say that he was going to see to it that Mabel received a good education, even to going to college.

Mining was and still is a hazardous occupation. One day, Uncle Ike was seriously hurt in the mines and was taken by train to Denver, where he died. The length of his illness and the nature of it, and conditions surrounding it are not known. About all I know is that he died and his body was brought back to Evanston, where he was buried. Incidently, so was the college education for his niece. It is regrettable that we do not even have a death date for Uncle Ike. This is for later research. With his passing, there were but two left at home.

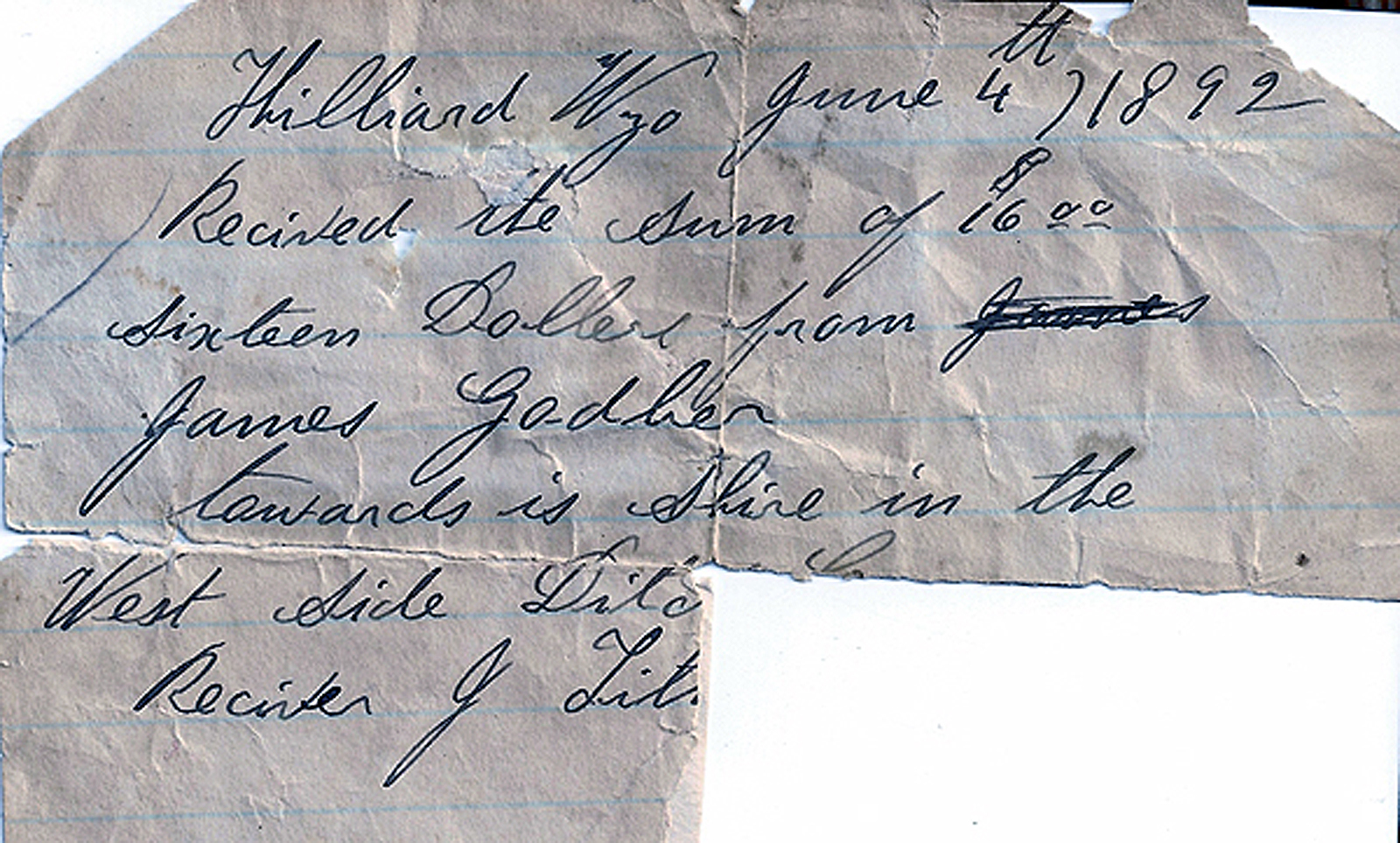

Receipt for a Share in the Hilliard West Ditch Company.

Receipt for a Share in the Hilliard West Ditch Company.

They had been in Almy for but a few years, when they decided to buy some land south of Evanston about twenty miles. The Godbers had come to America to own land, and not to spend their lives working in the coalmines. The exact date of their purchase has not yet been determined, but I have in my possession, a receipt that was dated 4 June 1892, and signed by John Titmus, which acknowledges the fact that James Godber had paid $16.00 for his share in the Hilliard West Ditch Company. Also, we have a copy of the Articles of Agreement and Constitution, as well as the by-laws of the above ditch company, which is dated 20 July 1895. The following are the names of the original stockholders: John Titmus, Sidney Cooper, Ephraim Harris, Matthew Harris, Mrs. Fanny Hutchinson, JohnWagstaff, James Godber, John M. Phipps, Henry Lester, John Bate, Jonathan Hones, William Barker, Mrs. Mary Hutchinson, Mrs. Ellen Clark, Henry Robinson, G.W. Carlton, Snyder and Mills.

How soon the Godbers moved to their new farmland we do not know. Most likely, they arranged with their employer to work in the mines during the winter months, but certainly they had to take some time during the summer months to "prove up" on their land and make preparations that they might make their home on their land. It is known that they were still in Almy on the 20th of March 1895, for while Grandfather Godber didn't work in Mine #5, they were in Almy at the time of the explosion of #5. Mother said they heard the noise of the explosion, as did all the community, and felt it rock their home, and saw the fire and smoke rise out of the opening of the mine. Undoubtedly, their witnessing of this terrible catastrophe, caused them, even more than before, to realize the dangers of mining, and convinced them even more that they were not making a mistake in preparing to make their home on the land which they now owned.

The cemetery in South Normanton

The cemetery in South Normanton

Far away, in the little English cemetery, lay the wife and mother, who had dreamed of owning land and a home in America. As the father and daughter, who was almost thirteen years of age looked at the land they had bought, they could see that there was hardship ahead, and that it all wasn't to be as pleasant and easy as a dream might depict it. The land was dry and hard and covered with tall sagebrush, and everywhere were rocks. Hills were on both the east and west sides of the valley. Far to the south were the Uinta Mountains, snow-capped, peaceful and serene. I wonder if they looked back at the trail they had come along and hesitated? Surely they must have wondered if there wasn't an easier way to earn a living than that which lay ahead, if they stayed. As they, perhaps, hesitated, did the spirit of the wife and mother whisper faith and courage to her loved ones? This was her dream.

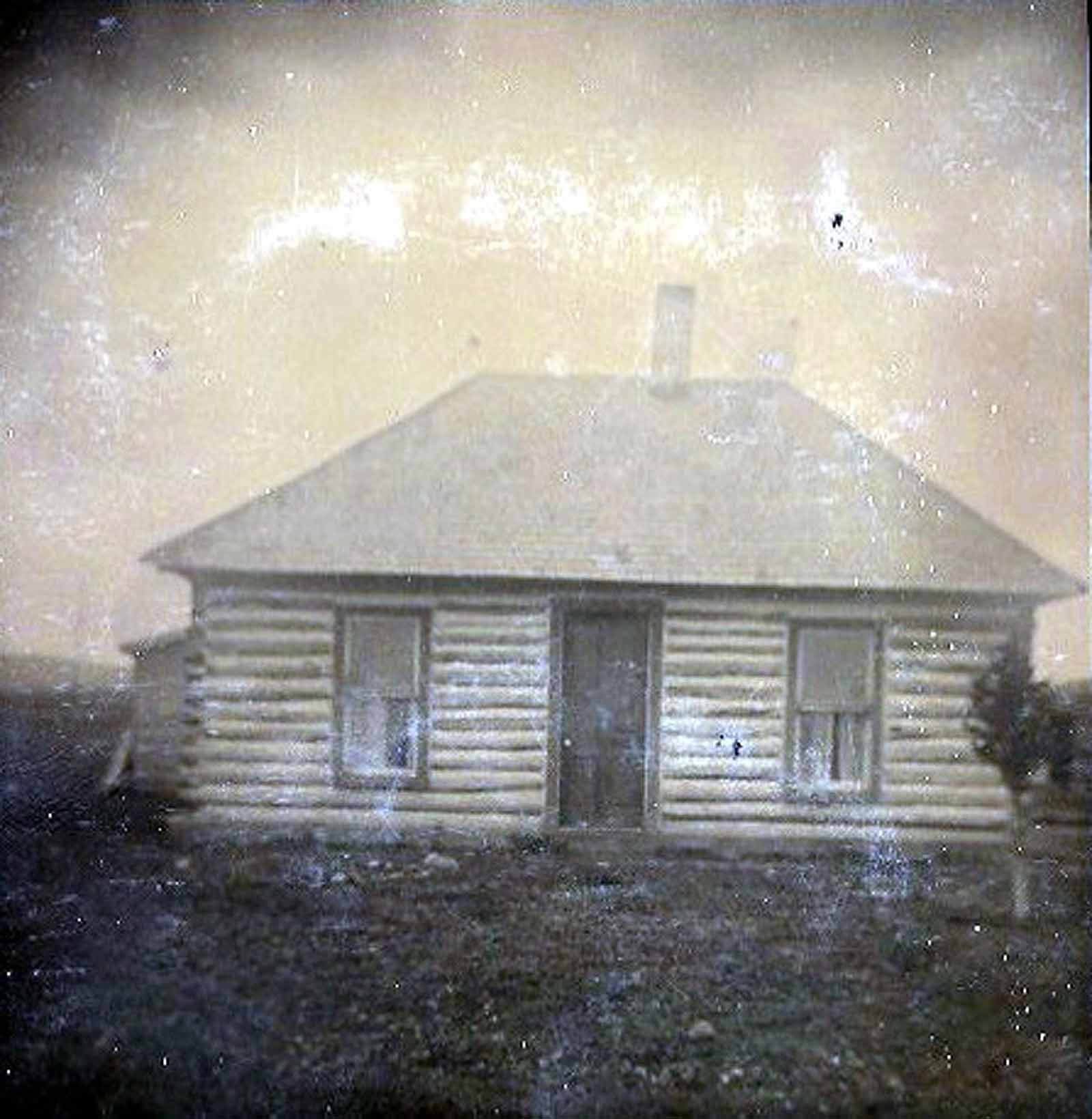

Dreams have their place, but they knew it would take more than dreams to build a home here. This was stern, hard, unyielding nature in the mountains of the West. The land was only to produce according to the sweat, toil and tears that man was willing to give. First, a well had to be dug to get water for themselves and their horses, Prince and Chief. Land had to be cleared of sagebrush for a house, garden and barns for the animals. A ditch had to be dug by plow and shovel from the Bear River miles away. Logs for a home, the barns and poles for the fences had to be hauled from the hillsides, also miles away. The bare necessities of life, which could be purchased only in stores, were also miles away - twenty - in the other direction. But to work they went, for they were full of faith and courage, or else too stubborn of determined to turn back.

The summer seasons were short, and when the early frosts would sweep over the valley, turning the hillsides into the golden beauty of autumn, they would return to the mines in Almy, before the cold, hard, bitter winter would set in. It was necessary that they go to the mines and work in the winter in order to get enough money to work their place in the summers. One might observe that this land was a luxury or a hobby.

But the storms of winter passed. The snow piled high in drifts by the winter blizzards would melt in the sunshine of the coming warmer weather. The waters of spring would push their way through the banks of snow to the creeks, and from thence, down to the river. The grass would grow green and beautiful. The dandelions, buttercups and other early wild flowers would blossom, and the days would grow fair and warm. And then the folk would return from the mines to spend the summer continuing with the building of their homes and preparing the soil. The work in the daytime would be hard and difficult, but the nights were beautiful and quiet. The frogs in the ponds serenaded them, and an occasional dog could be heard from the neighboring homesteads. At coyote howl in the distance, or even close at hand, was their nighttime serenade, and the stars twinkling in the deep blue sky, as the moon rose full and mellow, was their benediction as they lay down at night for rest.

Summer followed spring with hot days and much hard work. The spring flowers faded and the sunflower, the bluebells and the Indian Paint Brush, the sego lilies and other flowers grew in abundance. As I write, it may sound that life was all hard and that only the strong things managed to survive. This is not altogether true. Among the rocks, sagebrush and dryness, there grew a most fragile and lovely flower with the most exotic fragrance. Its life was short, but so beautiful! If I ever knew its name, I have forgotten. To me, it seems it might have been of the lily family, but of this I am nor enough of a botanist to be sure. The weather in the valley of the homestead was not always calm, nor the nights always warm and beautiful. Often black clouds filled with rain would come in over the mountains or hills, and rain would give water to the thirsty ground. Usually, as it rained, the lightning flashed and thunder rolled, and these electrical storms filled my mother with fear.

The days of childhood had passed and Mother assumed the role of the head of the home, and also, took the place of the sons that had died so many years before. She often told us of going looking for the horses, walking for miles around the country, until they got their land fenced. She learned to care for the cattle they bought, and raised, and she learned to milk cows, make butter and to care for the chickens. Cooking, of course, she had to learn early. It was a full time job to provide even the bare necessities of life. Of course, their own bread, cakes and pies had to be baked. The gardens they planted in this high altitude -- 7,000 feet-produced only the simple early vegetables, such as lettuce, radishes, carrots, peas, onions and perhaps a few potatoes. Horse-radish, which grandfather planted is still growing amid the hay crop (1967). Sage hens, rabbits, and mushrooms were provided by Mother Nature, but they had to be sought after, and gathered. Sheep men would use the country for their summer grazing pasture, so oft times mutton was purchased from the herds.

Mother's younger life, to us, seems to have been a quiet, dull one. Her father's brother, Henry (nicknamed Harry) with his wife, Louise and daughter, Sarah, who was younger than Mother, came from England. When, or where they lived, I wish I knew. I don't know why nor when, but Uncle Harry's wife, Louise, left her husband and daughter and went to Canada to live. Sarah came and lived with Grandfather and Mother for awhile. Mother seldom spoke of it, but she did say how badly Sarah felt to think her mother would run off and leave her. These two girls, Sarah and Mother, enjoyed the association of each other very much. Sarah married early to Cyrus Wheelock.

The Godber's recreation was as home made and as nourishing as the bread they provided for themselves. Sometimes, during the day, a friend would drop in for dinner, or a neighboring family would spend the evening with them around the kerosene lamp, and they would discuss the weather, the progress of their affairs, or of their lands and places of birth. Also, religion would be a topic that would help to pass the time. Church socials and parties were also held and attended. Traveling ministers would hold out in the homes, and also, the Mormons had their meetings. Mother, in search of the truth, attended them all, but I don't know if Grandfather was interested one way or another. He may have gone just for a place to go, and yet, I shouldn't say that for as stated earlier, I never knew him, so I can't judge.

The ditch from Bear River was finally completed, and water flowed out onto the land, the sagebrush was cleared off - a hand-job process, and seed was planted in the ground. In a few years, it was necessary to cut the grass with a scythe (I still remember Grandfather's) and thus they were in production. Within a few years, a mowing machine was added. From records from the County Court Office in Evanston, Wyoming, we have the date of Grandfather's land patent from the United States government to be 22 May 1899, and it was recorded the 9th of February 1900.

Herbert Brown and Mabel Alice Godber wedding picture

Herbert Brown and Mabel Alice Godber wedding picture

The years passed, and somehow, somewhere, Mother met the man who was to be my father. Since I wrote that sentence, I've sat and wondered why I never asked one or the other about their first meeting. I wonder if it could have been in Almy, Spring Valley, or at Hilliard, as my Grandmother Brown had a homestead about three miles from the home of the Godbers. I don't know how long they went together before they decided to get married. Spring Valley was a mining town several miles south and east into the rolling hills from Almy. Many of the Latter-day Saints moved from Almy when those mines closed down, in order to work in the mines in Spring Valley. I just imagine that Mother and her father had gone there for the winter. Be that as it may, Mother was married the 24th of December in 1900 to my father, Herbert Brown, at Spring Valley by the presiding Elder of the Spring Valley Branch, Edward Burton. Father was a member of the Mormon Church.

Spring Valley was a dry desolate place. Water had to be hauled in for drinking purposes. The first two children of my parents, Alice Harriet and Violet, were born in Spring Valley, Alice being born on the 13th of October 1901, and Violet, the 21st of July 1903. I believe that it was after the birth of Violet that my parents moved back to Hilliard and lived on Dad's mother's homestead for a year or two. This place was about one half mile east of where the schoolhouse and the old church building were later built. The house was next to the north/south road, which goes up the east side of Hilliard Flat.

One summer, they went to Almy to visit with Grandmother Brown. Grandfather Godber went with them. During their visit one evening, they were outdoors watching an electrical storm to the south. Mother said that they made comment that it seemed such a terrible one. A few days later, they returned to their home and found it had been hit by lightning. Although it had not burned, it was badly damaged. It seems that the lightening must have been hit twice. One shaft of lightening seemed to have hit the ground close to the house, run under the house, lifted up a part of the bedroom floor, and laid it on the bed. Another shaft had come down the chimney bringing out the soot along with it, blowing all the stove lids off and scattering the soot all over the house. The cupboard was hit and all the nails that held up the shelves melted, and all the shelves and dishes were in the bottom of the cupboard. Windowpanes had been blown out of the windows and were lying unbroken away from the house. They were thankful they hadn't been home at the time, and as long as she lived, Mother was afraid of lightning. The fall of 1905 came, and that winter, Grandfather and my father and mother decided to go to Glencoe, Wyoming to work in the mines. Grandfather's brother, Harry, was working in the mine in Diamondville, and Dad's brother, Frank, was in Glencoe. This may or may not have influenced them to go there. Grandfather became very ill, and the doctor was called. He had pneumonia. He had been seriously ill with pneumonia before in his life and was afraid that if he ever got it again, he wouldn't live. The doctor came for several days each morning, and the doctor seemed to think he would be alright. Grandfather had a sense of dry humor, which had helped him through life. This particular morning, the doctor left laughing because of a joke Grandfather had told him. As the day wore on, Mother could see that her father was leaving her. In a few hours, he was delirious, and was speaking of people and life in England. Before the day was ended, he had gone to be with his loved ones. His earthly mission was ended. His part of Mother's mission was done; hers was still ahead of her, and she must now go on alone, and yet she was not alone, for she had my father and two children. Grandfather's body was taken to Evanston and was buried by the side of his brother, Isaac. Grandfather died the 30th of January 1906, and he was not quite sixty-three years of age. His earthly life was over, but I can appreciate only in part the many things for which I am indebted to him. I'm sure his life was difficult and lonely, because he was to be a part in bringing salvation to his family. He never realized in this life how important his mission was. For us, we do know, and we say, "Thanks, Grandfather, thanks." One other thing I am most appreciative of is a little saying of advice he used to say to my mother, "Mabel, just don't murmer."

James Godber

James Godber

Father, Mother and the girls returned in the spring to the home of Grandfather Godber. Eldest daughter, Alice, tells of the sorrow and tears of Mother as they entered the log house her father had built, and which held all his possessions. Now the home was hers, and would be for the rest of her life. His two horses, Prince and Chief, were still alive, and they lived on until they died of old age.

Tombstone of James Godber and his brother Isaac

Tombstone of James Godber and his brother Isaac

It was after the death of Grandfather, that Mother accepted the Gospel and was baptized. She was baptized the 11th of November 1906, in Bear River, near the home of Grandfather and Grandmother Brown in Almy. A hole had been cut in the ice, and she was baptized. Later she said that the water was so cold that she didn't know if she was frozen or scalded. Then she went into Brown family home to be confirmed a member of the Church. This date and event were very, very important for the ones who had gone before, as well as for the ones who came afterward. Perhaps more important than any of us realize.

The years passed. Father and Mother lived on the ranch, continuing to clear the land of sagebrush, to produce more hay, so they could have more cattle and sheep. The water wasn't too good where Grandfather Godber had dug the first well, and the log house wasn't like they wanted, so another house was built, and later, still another one. The last one was the one I grew up in and loved so much. I can remember how we used to play in Grandfather's old house. It had a lot of interesting things in it.

Click here to read an account of her life written by her granddaughter Elaine Brown Harris

Violet, Mabel and Alice Brown in Hilliard

Violet, Mabel and Alice Brown in Hilliard

I, another girl, was born in Almy, and was named Mabel May, with my birthdate being the 20th of May 1908. Two years and a week later, still another girl, Dorothy, was born the 27th of May 1910, also at Almy, due to the fact that Grandfather and Grandmother Brown lived there. I recall the joys of home with Father, Mother and sisters. We all seemed to be well and happy, and had plenty of food and other necessities of life. My parents helped in building up the community. They assisted in providing school, a church house, ditches, roads, and the needed things to have a better place to live. They, with the rest of the people, attended parties at each other's homes, worshipped at church, squabbled at school and ditch meetings, helped those who needed assistance, sat up with the sick and dying, helped bury the dead and comfort the living so they could go on again, heckled each other about politics and found joy in living. Above all, they formed eternal bonds of friendship and assisted each other to survive in the community.

Mother always kept in touch by letter, with her cousin, Sarah, who had married Cyrus Wheelock and had moved to Auburn, Wyoming in Star Valley. One Christmas, Sarah and Cyrus invited Mother to visit them in Auburn. We had started from home by sleigh until we reached Evanston. I can very vividly recall being in the railway station waiting for the train. I had a doll, I guess an early Christmas, and it was night. The train came, and we all got on excepting Dad. We were met in Montpelier by Sarah and Cyrus, with a sleigh and team. We rode for a long time, it seemed, and after a long drive, we got to a halfway place, where we stopped for the rest of the night. We got up early in the morning, ate and then went on to Sarah's home. I recall a visit to Afton, while we were there, and a few things while being with Sarah, Cyrus and their children. I know we went back to Evanston the same way that we left, but that is about all I remember of the trip. I do recall arriving in Evanston, and going to the home of one of Mother's friends, and then I remember Dad coming and taking us home.

There were different things my parents had to do to make a living. As a young girl, I found it a great deal of fun to climb the bales of hay, and to watch the horses go round and round, with the men feeding the hay into the bailer, and to see it come out in bales. It was fun to watch the little lambs, but I surely hated to herd the sheep, especially when it was an all day job. We would either take our lunch, or have some one bring it to us. I recall several times when the sheep were left alone, that the coyotes helped themselves. The folk had some cows, usually one or two to milk, several for beef, and some to sell. Also the horses were a must. My father often hauled hay either to Evanston or to the men in the hills, who were cutting ties for the railroad. We would load up in the afternoon, get up early the next morning, and would not get home until late at night. One of my early memories was waiting for Dad to come home. Mother did the chores while he was gone.

My folks were very desirous that their children get a good education. I guess it was because their own opportunities had been so limited. My father was always on the school board, or so it seemed to me. I surely used to hate this. If anything went wrong, my Dad always seemed to get the blame. The problem of getting to school was the problem of each family. Dad and many times Mother would take us either by buggy or by sleigh. If it was stormy, they would be there at night to take us home.

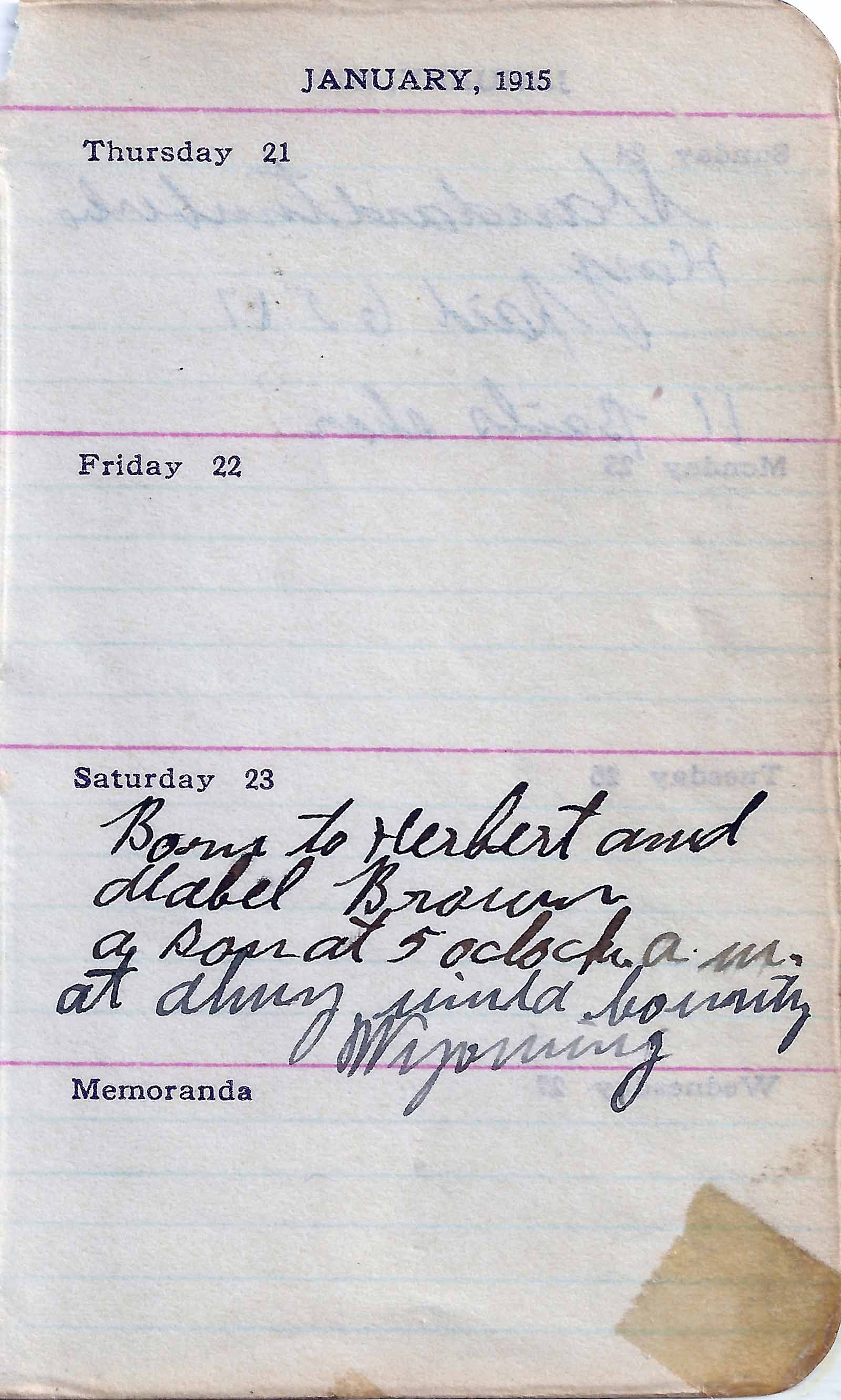

Herbert Brown's Datebook

Herbert Brown's Datebook

I have a little book in which Dad kept important bits of information. In this book, under the date of January 23, 1915. he says: "This morning at 5 a.m. a son was born to us." We called him James Herbert. I can remember the folk getting up that morning and taking us to school in the sleigh, which was half-filled with hay and blankets. They left us three older ones, and took Dorothy with them. Next night, Dad was home and told us we had a brother. I'm sure that Dad loved us girls, but after a four straight run, a son was at least a change, and he was proud of him. Now, he'd have a son to help him someday in the future. It was in mid-winter when Mother came home with the tiny baby to care for.

While we children were small, all the work had to be done by Dad and Mother. Water had to be pulled from a well by a bucker on a rope. After climbing over at least one large snowdrift, many times shoveling out the door of the well house and breaking the ice, one then had to carry the water back over the drift into the house, to be heated on the stove. The clothes had to be washed on a washboard, and boiled in a copper boiler and then hung on the clotheslines to be immediately frozen, along with the fingers. From the clothesline, the frozen stiff clothes were taken back into the house to be processed for use. If ironing were necessary, the irons were heated on the stove. The stove used wood, which had been brought by wagon in the fall from the canyons, sawed by hand, chopped and carried into the house the distance from the woodpile which always seemed longer in the winter than in the summer, because of the snow drifts.

Mother, with the wildest of her daydreams, could never have foreseen that her children and grandchildren would someday put clothes into a washer, press a button, and have their clothes come out in about half an hour, clean, but damp. And then to be put into a drier for another fifteen to twenty minutes and come out dry, all with no hands either cold nor wet, and no water to carry in or out. Also, Mother made a lot of the soap she used in the laundry.

Dad and Mother were always interested in the news, and subscribed to a newspaper. The one I recalled as being her favorite, was a weekly, called the Pathfinder. It was published in Washington D. C., and so the news wasn't always new, except to us. They often subscribed to a Wyoming newspaper. The mail was delivered daily. The earliest that I recall, was delivered by horseback. We were not on the toad traveled by the mail, so we had our box at the end of the lane that we lived on, about a half- mile from the main road. Getting the mail was one of our daily jobs. In the summer, it was a wonderful adventure, as well as on nice days in winter, but on other days, it wasn't so wonderful. I remember being sent one day, and it was cold and storming with snow falling. I got the mail and read the headline of the newspaper, that President Joseph F. Smith had died.

Modern conveniences became a little more common, and eventually, came into our community - the telephone, and the car. A few of the neighbors had one or both. We had neither for a few years. Airplanes began to fly overhead, and life began to be easier for all.

I guess Mother and Dad had given up the idea of more children, when they found out that another was on the way. He was born the 15th of September 1924. To us all, he was the most beautiful baby, the smartest, and the most wonderful thing that had ever happened. He was given the name of Melvin, because Dad's favorite Church leader was Melvin J. Ballard. Melvin's second name was Adin, for Grandfather Brown.

Out of my memories of Mother and her life, comes the sweet comfort of her large, black woolen shawl. I don't recall when she first got it, nor how she came by it, but when illness came and warmth and comfort was needed, Mother would wrap us in it, and its magical comfort would help with what was needed. I do not know whatever happened to it, but suspect that it wore out after years of service. It's part in our lives is still a treasured memory.

In this day of plenty and progress - men landing on the moon, superjets, supermarkets and many more supers - when things seem so common and plentiful, I think of the many things we didn't have. Take for example, an egg. That seems about as usual and commonplace as anything can be. But at certain times of the year, an egg was really something! For months, we'd only had an egg or two for Christmas, as the hens had quit laying, but then one day in late winter, Dad would come in proudly from the outdoors, holding an egg in his hand. That was the biggest news of the day. That egg was carefully put away to be joined by another in a day or so, and then another hen would go into production. Maybe in ten days or more, we'd have an egg to go around; or us little kids would be happy to have half an egg. Usually it would be a Sunday morning when Mother would fry the home-cured bacon and eggs. This was a real treat. I can still recall standing by the stove as Mother broke each beautiful egg into the pan. Until fall, we would have enough eggs.

When summer came around, we would help Mother get the broody hens set, and waited the twenty-one days for the chicks to hatch. This way, we would have hens to lay our egg supply for the next season, and the roosters would be reserved for special dinners, such as at Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Years.

Saturday night was bath night, just as surely as Saturday came around, especially was this true when we were little. If there was a baby, Mother bathed it every morning with Cuticure soap. This bathing session was a real task. All our clean clothes had been washed, ironed and made ready. The room was made warm, and the water had been heated in the big washtub, and additional was stored in the stove reservoir. Two chairs were placed together, one facing the other, and the tub placed on these so Mother could handle us easier. Starting with the smallest of us, we would be washed, hair and all, and then we were dressed in our clean clothes, hair braided and thus be ready for bed. Mother had usually baked bread and made butter and we would have some before we got into bed and out of the way, so the bigger girls could take their baths. Dad usually emptied the tub and carried the water outside.

The Brown-Godber home in Hilliard

The Brown-Godber home in Hilliard

Our lives were closely knit together, for we worked together, ate together, and enjoyed ourselves together. The big kitchen, heated by the big wood and coal range was the focal center of our home. We depended on the stove to provide warmth for us, to cook our food, heat our water and to comfort us against the elements and life itself. Things seemed better with the warmth and glow of the fire. Especially was this true, when on cold winter nights, we'd sit around the stove, keep it full of wood, and sometimes coal, open the oven door for extra heat, and it we had some, popcorn, eat apples, or Dad's homemade molasses candy. Out of the big oven, Mother would bring out her homemade bread, cakes, pies, rice puddings, apple dumplings, roasts of mutton or beef, her pork pies and "savory ducks".

Close by the stove in the middle of the room was the big, round table with its oilcloth cover. It was big enough for all of us, usually eight, to sit around, and we each had our place. The table was all things to all of us. On it, our food was prepared, we ate, washed the dishes, used it as a "cutting out" board on which our clothes to be made were cut out. Clothes brought in from the clothesline outside were dampened, folded and prepared for ironing. Meat to be cut or cured was all prepared on the kitchen table.

Evenings would find us as a family, sewing, studying, reading, playing games of checkers, dominoes or tiddley-winks, or just talking and visiting -- all by the light of the kerosene lamp. By this lamp, we learned our lessons in reading, writing and arithmetic, and how to spell, and about the wonders of the world, its places and peoples, and the doing of men in the world history books. Around this table, we read about Joseph Smith, the Book of Mormon, the Bible, and our few Church books. Progress came years later by the advent of the Coleman lamp. Now we could read away from the table.

I can't remember when Mother wasn't afraid of a thunder and lightning storm. A mouse, the dark, or spooky things held no fear for her, but clouds gathering on the horizon, and flashing lightning, always caused Mother to do one of two things, depending on where Dad was. If he were home, Mother would go to bed, cover her head with a pillow and stay there until the storm was over. If Father wasn't home, she would watch the storm's progress, and before long, if it came near, she would call us together, and we would soon be at our neighbors, the Martins. In my mind I can still see my father standing by the door, watching the progress of a storm. His comments would be, "That was a good one!" or "That was close!" As if it were yesterday, I recall one day burning piles of sagebrush that Dad had cleared from the small piece of ground close to our home. He was away, and Mother and we kids were working when a storm began to gather, accompanied, as usual, by lightning and thunder, It wasn't long before we headed toward Martin's place.

Speaking of sagebrush - we'd have wagonloads of the stuff to be burned as firewood. For a quick, hot fire, nothing was better, and it smelled so good. Nostalgic memories - coming home after a hard day in the fields and smelling food cooking and sagebrush burning!"

Traveling salesmen: I remember Watkins and Raleigh salesmen with their outfits best. Each would come into the community about two times a year. At first they came with horses and wagons piled high with their goods - spices of all kinds, vanilla and lemon extracts and nutmeg, salves, liniments, cold remedies and such things. Mother always bought a laxative herbal tea - good for anything, even for troubles we didn't have, and it was the nastiest stuff! The salesman also had colic and bloat medicine for the cows and horses.

Occasionally a dry-goods peddler came around, and he would display all his bolts of materials, laces, buttons, pins and whatnot. In the summer time, farmers from Utah would bring their berries, fruits and vegetables to sell. Our community, being twenty miles away from Evanston, the nearest town, the Hilliard Flat area was an ideal lace for such salesmen as I have mentioned - and every other kind, I might add. Actually, they were oft-times a blessing to us, for they would save a long trip to town in the buggy or wagon.

The original LDS Church and community center. The building has been moved from its original site to a neighbors near the Brown home.

The original LDS Church and community center. The building has been moved from its original site to a neighbors near the Brown home.

The inside of the church. The pictures were taken during a Brown family reunion on July 13, 2002

The inside of the church. The pictures were taken during a Brown family reunion on July 13, 2002

The winters were long, and after the holidays, parties were held at each other's homes, usually on Friday nights. Some would take sandwiches, others, cakes or pies, pickles, etc. The hostess would make cocoa. Games were played and if there were anyone in the group who could play a fiddle, there would be dancing. Oft-times, the older folks would play types of card games, and naturally, all this time a lot of visiting was going on, and everybody got caught up on the news and gossip of the community. At midnight, supper was served. After this, the timid souls would go home, but many times all would stay until morning, and have breakfast together, and then they would go home to do their morning chores, and then go to bed.

Not only were families bound closely to each other, but the whole community was held together by ties of church, school and community interests. In some way or the other, active or otherwise, all were Latter-Day Saints, and every family had children in school. School programs were part of the social life of the community. Small programs were sometimes held at schools during the afternoons, but at Christmas and the end of the school year, the affairs were "super productions". Every child participated either in song, dance or a play, from the little first graders to the eighth grade. The programs were held in the church building. The building was scrubbed, cleaned and decorated with crepe paper until it was a thing of beauty. A tree was decorated and names drawn so that every child had a present and a sack of candy and nuts. The expense was handled by the parents of the community. Following the school program, the seats were moved from the middle of the floor to the walls, and dancing was next. At midnight, a luncheon was served of sandwiches, cakes and cocoa, which had been brought by each family by assignment. Usually after this, all but the real dance lovers went home -a perfectly complete evening and prelude to Christmas. Mother, as well as other mothers had made a new dress for all the girls, and they were worn as proudly as New York or Paris creations ever have been. Style is only what gives joy and beauty to the wearer.

The summer also had its celebrations - the 4th and 24th of July. Nearly everyone of the community would be present at the gathering, which usually, would be in a grove where a bowery had previously been made for the occasion. Following a program which was arranged to fit the occasion, each family would spread a quilt on the ground with a table cloth on top of it, for the table spread. Following a community prayer and blessing on the food, all would eat their own food, trade, sample other, etc. Lemonade was usually served. It had been made in a tub, and each family would take a portion to their "table" in a pitcher or bucket. After the lunch, games were played - mostly races starting with the littlest children and ending up with a "fat man's" race. Maybe a ball game would be played while others visited. Toward evening, all would go to their respective homes to do the chores, and meet again at night for a dance in the church.

Root beer in the summer time - what a flood of memories that brings. We kids would go on a tour of the ranch, finding a few choice sprays of sagebrush, some wild grape leaves, a little plantain leaf, some yarrow, which had its little white flowers on top of its ferny stem, and lastly, quite a few dandelion leaves. All these would be taken home, washed, boiled and strained. This was added to about ten gallons of warm water, a bottle of Hires Root Beer Extract, some sugar and yeast. It was covered and kept warm all night, and bottled the next morning. We had gathered bottles as we had traveled along the roads. Most of them were beer bottles. Before we started making our kind of beer, we'd take the bottles to the ditch, put a few small rocks and dirt in them and a little water. A good shaking would clean the bottles, and then we would rinse them in clean water and take them to the house and wash them with good, clean, soapy water. Before we got a capping machine, we would use corks and tie them on with a string. We'd then take the bottled root beer to the cool of the well to await for four or five days to "work good". On a hot day in the hay field, we'd take a few bottles to drink during the afternoon. Also, after the work was done and just before bedtime, a glass of homemade root beer was a delight.

I think it was about the fall of 1926, Dad and Mother, with four or five heads of other families of the community, decided to go into the dairy business. Many of the folk had found that there was money to be made in milking cows, separating the milk and selling the cream. The county agent agreed to buy some Jersey cows for them. I think he went to Bliss, Idaho or near by to it, where he bought the cows. We were thrilled when they arrived, but they hadn't had too much to eat and several died on the train. All were numbered, and those who had ordered them drew numbers. These Jersey cows, with their big, brown eyes - Blossom, Queen, Jewel, Patricia and Bonnie - changed our way of living. It was our job night and morning, to milk the cows, separate the milk, feed the calves, and once a week, churn the cream into butter It was then formed into individually wrapped pounds, which was sold to Blythe and Fargo, a large mercantile store in Evanston. They had regular customers for Mother's butter. It seemed a big job, but it was a regular income for us. What was it--- a hundred pounds of butter a week? Well, more or less, and usually an eight or ten gallon can of cream to sell to the creamery.

Alice and Violet Brown

Alice and Violet Brown

Within a few years after Melvin's birth, Alice and then Violet got married and left home. Alice went to Kemmerer, Wyoming, and Violet to Caliente, Nevada and then to Melford, Utah. Marion, Mabel, Louise and Junior - grandchildren - took their places in our lives and hearts. It was the summer that Junior was born, that my father began to be really sick. For years, he hadn't been too well, but one day he became seriously ill. We were haying and were hurrying to get done. It was one afternoon and Dad had been mowing, when I went to him, carrying a drink of water, and to see if I could help in any way. He said, "Will you finish mowing for me so I can go home and rest awhile?" That was the last day he ever worked in the field. The next day, he went to the doctor, and after a few days of staying in Evanston with Bill and Alice, he went to the hospital in Salt Lake.

He came home to get a few things done for the winter. Day after day, he seemed to get worse. As I write this, I can understand how he and Mother must have felt, because they both felt how close the end of our home life together must have been. He knew how needed he was by his family. Winter was coming on. There was so much to do. Four children were needing to be raised yet, and life had been and was so sweet. How he must have hated to leave home knowing he would never return. He had been ill most of the night - Jim and Melvin were sent to school. Dorothy and I did the chores, and then Dad, Mother and I started for town. On the way, we stopped at the church where both of them voted, and then we went on to Evanston. Mother stayed with him at Bill's and Alice's, and after a few days, he went to Lava Hot Springs, where he had uncles and other relatives. He hoped that he would feel better there. After a few days, a call came for Mother to go, and a few days following that, all of us were called. The snow was deep. We had to shovel a path out of the garage to get the car out. Neighbors pulled us through the snowdrifts to the main road, and Dorothy and I started on the way. We picked Jim and Melvin up from school, and went to Evanston, where Alice and her little girl, Marion, were ready. From there we went on to Almy, where Uncle Lyman (Dad's brother) was ready to go with us. This 22nd of November 1928, is a day I shall never forget. It was about 8:00 p.m., when we arrived at the hospital in Lava. A few of Dad's folks were waiting, and the nurse led us to Dad's room. I went in first and saw a sheet over someone. I knew Dad had left us. Why someone hadn't told us, I'll never know.

Lava Hot Springs Hospital

Lava Hot Springs Hospital

Mother was left again. Again the responsibility was hers. Bill and Mother left early the next morning for Pocatello with the sad task of taking Father there. We left by car and arrived in Evanston before the train. In those days, the dead were taken to a home, and as Bill and Alice were the only ones living in Evanston, our second home was there. Oliver and Violet had arrived, and as the time for the train arrived, I felt I couldn't stand this great sorrow that had come into our lives. Whatever would we do without him? The whistle of the train pierced the near-midnight November cold air, and also my despairing heart.

Mother was brave and courageous as she returned. The casket with the body was brought directly to the house, and as it was pushed into the room, we all felt Dad was there with it, and a peace came into our hearts. Each of us felt to say, "Life must go on, but Dad, your place in our hearts is, and will always be dear to all of us." After the funeral, the bishop of our ward, who was our closest neighbor and friend, said that several months before, he had dreamed that he was at the railway station waiting for Dad's body to return home. As they were waiting, he said, he saw Dad walking around among the folks, but no one paid any attention to him.

This was a difficult time for Mother, but there were her children to help carry the burden, and all did.

Dorothy married the next July, and then I was called on a mission. Leaving Mother was a difficult thing to do. If she had shed one tear, I would never have gotten on the train. I said, "Mother, if you need me, I'll always be able to come back." She said, "If we all die, and if we have to sell the ranch, we'll see that you don't dome home until you are released." The family who took her back from the train on which I departed, said that she shed plenty of tears after I left.

While I was in Salt Lake at the mission home, Alice and Bill had a son born to them, Billy. Melvin contracted scarlet fever the first winter I was away. For nearly ten days, Mother hardly slept excepting at his bedside. Her watchful and loving care aided in his recovery. Elaine, daughter of John and Dorothy was her next grandchild. Mother always tried to be one of the welcoming committee for all her grandchildren. She loved all of them.

The years passed. She had trials of all kinds, and it was she who had the final decisions to make about buying, selling, and the everyday routine of life. Many times she was lonely and unhappy, but then many times life was good and all was well. As the time went by, we began to notice that Mother wasn't as well as she should be.

World War II began in 1941, and Melvin was just the right age to be drafted. He made up his mind to enlist in the Air Force. This was a hard and trying time for Mother. Loyn and I were living in Evanston and Mother was staying with us. Loyn's Dad and Mother came for a visit, and I slept with Mother that night - but we didn't sleep. She tossed and turned all night, and the next morning she told me that she had made up her mind that all would be for the best. She said something like this: "My father and I came here to America in search of a home. We have enjoyed a good life in this good country. Now I've got to pay the price, but Melvin has had his patriarchal blessing, and it promised him he would lay down his life in peace, so I'll trust in that." She went to town during the next day and bought herself two pair of shoes. When my mother wrote this history she forgot mention her marriage to Edward Loyn Blacker. They were married 9 October 1936 in the Salt Lake Temple. By 1941 they had a son Paul and a daughter, Ruth. (Ruth Blacker Waite)

Loyn and I moved to Rupert right after this, and Mother bought our home in Evanston. She often visited us in Rupert. She came to help when Mary was born, and seemed more upset than usual. She said she had two strange dreams and she felt she hadn't long to live. Mother had inherited the superstitions of England. (We've laughed at her for years, but she would always say, "You'll see.") She had gone through a spell of breaking things - dishes, mostly, and her bread would split while in the oven while baking. While she was with us, she broke several dishes, and the lampshade in the bedroom. I tried to joke her out of her feeling of depression, but didn't succeed. One of her dreams, as I remember, was something like this: She was in a room. Her father was on one side and my father was on the other side. There was a woman in the center of the room, with her back turned so that Mother was unable to see who she was. In the dream, her father was asking my father for the woman. At first Mother was concerned about me, as everyone else seemed all right, but after Mary was born, I was fine. She decided that it was not me, but that it was she (Mother) whom her father wanted. She later found that she was again wrong in her superstition. In her other dream, she was standing on the steps of the Evanston 1st Ward chapel, listening to the singing at a funeral.

The meaning of the first dream started to be understood about Christmas time of that year. Violet began to be sick. It was serious, and an operation was ahead for her. All seemed to go well, but we were not given any hope for her recovery. Mother was staying with Oliver and the family in Ogden, and Violet was still in the hospital, when evil spirits came into the home. It happened one morning, as Mother told it to me. She awoke with a terrible feeling she had never before experienced. She could see no one, but it seemed as if she were being destroyed. She hurriedly dressed and went downstairs. Oliver was already there, and he had the same feeling. The downstairs part of the house seemed all right, however, as soon as either started to climb the stairs to the bedrooms upstairs, they could feel this terrible influence. Mother said it seemed as if the hair on her head was standing straight up. After awhile, Oliver said he was going to go upstairs and rebuke the evil spirits by the power of the Priesthood. This he did, and the influence or evil spirits left.

Violet seemed to be improving, so Mother came to visit us in Rupert. While she was with us, Violet died. Louise called us and Loyn and I had the sad task of telling Mother. This was something Mother never got over. Mother wasn't well at the time. She had a bad cold and cough, and the doctor even advised her to not go to the funeral, but she did. The funeral was held in the Evanston 1st Ward chapel. Just before the close of the services, as the closing song was to be sung, Mother had a coughing spell so bad that she had to leave. I went outside with her, and someone got her a drink of water, and the spell left her. She and I stood on the outside listening to the song and prayer, and Mother said to me, "Here's the meaning of both my dreams - Father wanted Violet for some reason, and here we are listening, just like I dreamed it." Violet died in Ogden the 5th of April 1945.

Violet Brown Scovel's Burial, 1945

Violet Brown Scovel's Burial, 1945

Mother had been interested in working for her dead relatives. Her father and Uncle Ike were about the only relatives she ever knew. She and Violet had done the work for all she had records for, and she had spent considerable money through the Genealogical Society, in search for additional information about her ancestry. She often visited the temple and wished she were well enough to go more often, but her heart condition didn't permit her to go. She did tell me, when she visited us in Ontario when Beth was born, that she was sure Violet had been called by her father to help with the work. Actually, following Violet's leaving us, there seemed to be more success in research work. Success in research remained slow, however, despite her hiring professional researchers, and Mother became very concerned. She often remarked of her wonderment as to why her records were so hard to come by, and felt that assistance would need to come from the other side of the veil. On occasion, she would say, "If I could go over there, I would stir things up!"

Melvin married shortly after Violet died, the 3rd of July 1948, to Mary Perkins, and after that Mother said she felt sure we could all take care of ourselves. Her feelings in this regard were expressed to me, as I am sure they were to many others of her family. Mother had a rather severe illness in the summer of 1947. I went to Evanston from Ontario, Oregon with Mary and Beth, when they were babies, and stayed for about a week. She was getting better, and we felt all would be well with her. I really enjoyed being with her for a while, and we talked about so many things. She told me she thought so much of her children - "They are all so good, and I feel I've done a good job. They can all carry on with the work in the Church, and are able to care for their families."

Lucille had come to Evanston from Hilliard, where she and Jim were living on the old home place, and she and Mother drove us to the train for our return trip home. This was the last time I saw Mother alive. As she stood waving goodbye as the train left the station, I almost knew it was our last goodbye, and I could hardly see her through my tears.

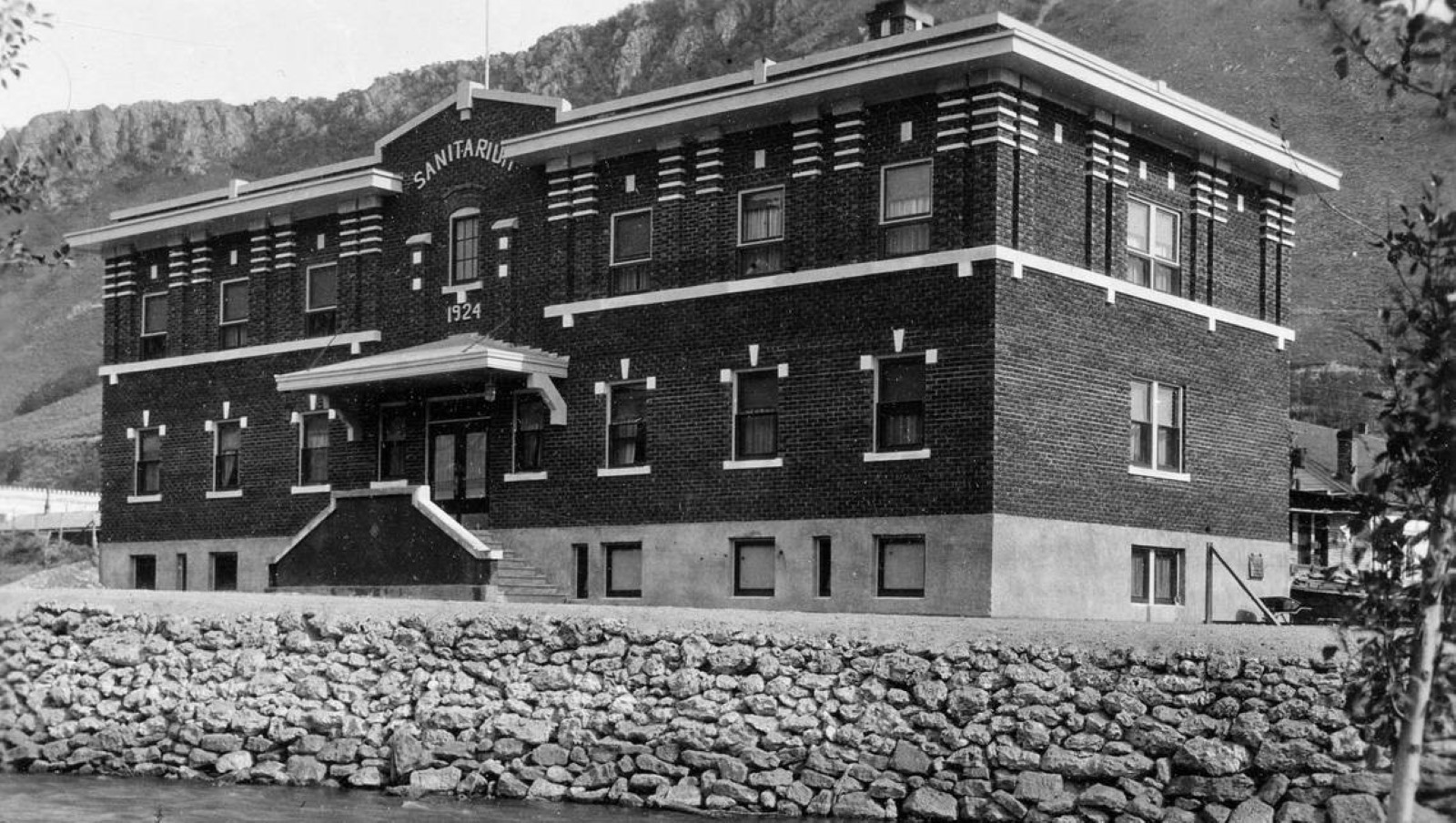

Evanston City Hall where Mabel Alice died

Evanston City Hall where Mabel Alice died

The months passed and Christmas came. She had told us by letter that she would try and spend that Christmas with us. We had invited her to spend the winter where it wasn't quite so cold, but for one reason or another, she delayed her coming. On the afternoon of January 5th, 1948, the telephone rang in our home. Brother-in-law John Martin, conveyed the message that was a shock. Mother's death was sudden. I had known the time would come one day, but this couldn't be true! This was too soon!

Mother was preparing to come to spend some time with us. Christmas time was a little too early, for she had other things she wanted to get done. She had gone down to the city hall to have the water and lights shut off. She was intending to take the afternoon train to Ogden, and then to continue on to Ontario, but her plans were changed. While transacting her business, she felt she had to have additional air, and walked to the outside door, where she slumped onto the steps. Help came immediately, and she was carried into the building and a doctor summoned, but she was gone.

She had answered another call, and took another route to other dear ones - and what a wonderful meeting it must have been. She was met by Dad, Violet, her dear father, and the mother, brothers and sisters she had never remembered or known in life.

She was buried in the Evanston cemetery by the side of her husband and our father, and not far from her father and uncle. Her mission was over. She had accepted the gospel and begun the work of redeeming her dead. Indeed, she "stirred" things up behind the veil as she said she would, for within months after her passing, some of the "impossible blocks" in research work were removed, and genealogical information came, for which she had sought for many years. Many of her descendants have spread the gospel she loved so much, as they have served missions for the Church.

Her influence is being felt on the other side of the veil, as also with us, as we go on through life. Thanks, Mother, thanks, and this from all of us.

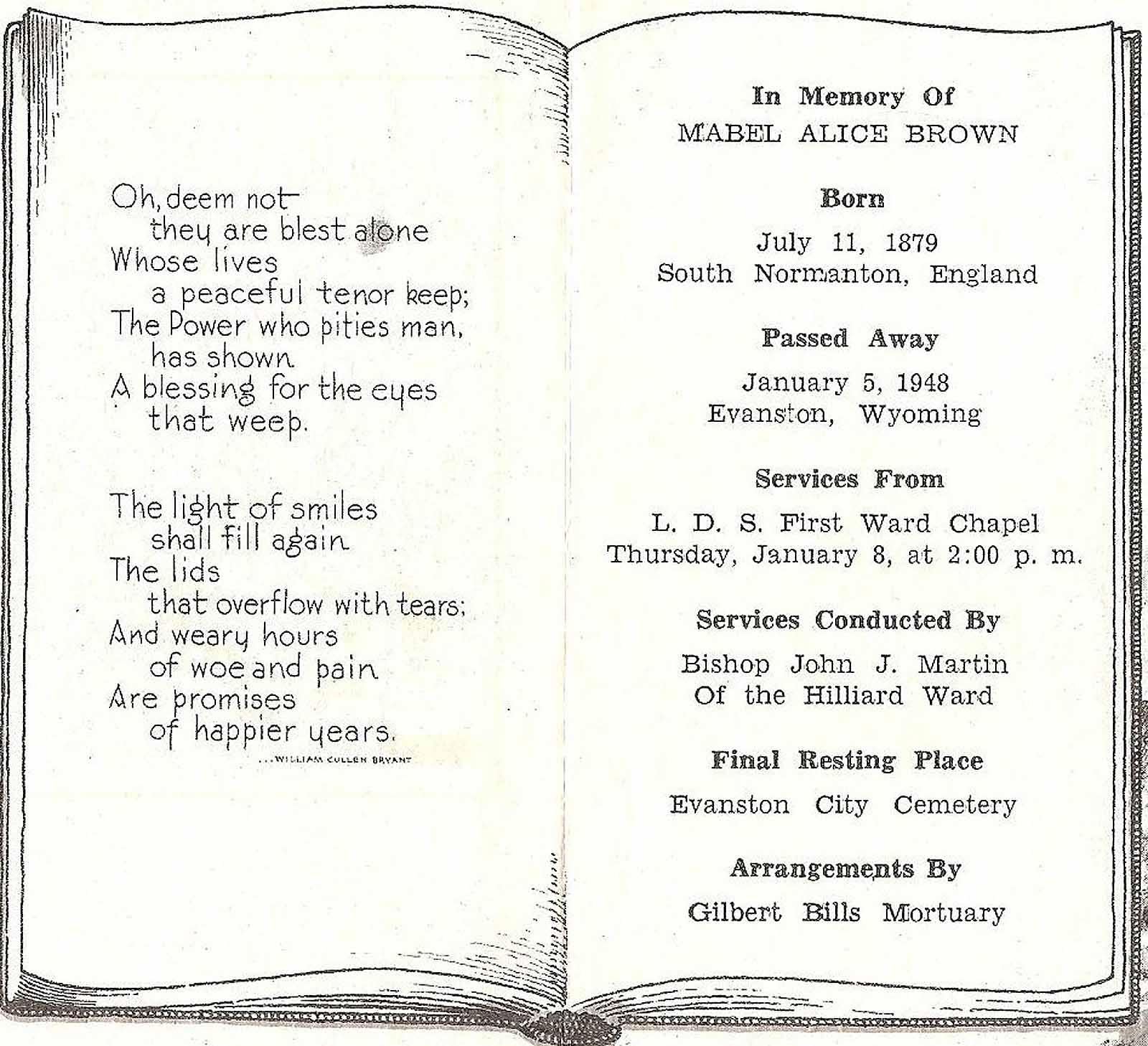

Mabel Alice Godber Brown's burial

Mabel Alice Godber Brown's burial