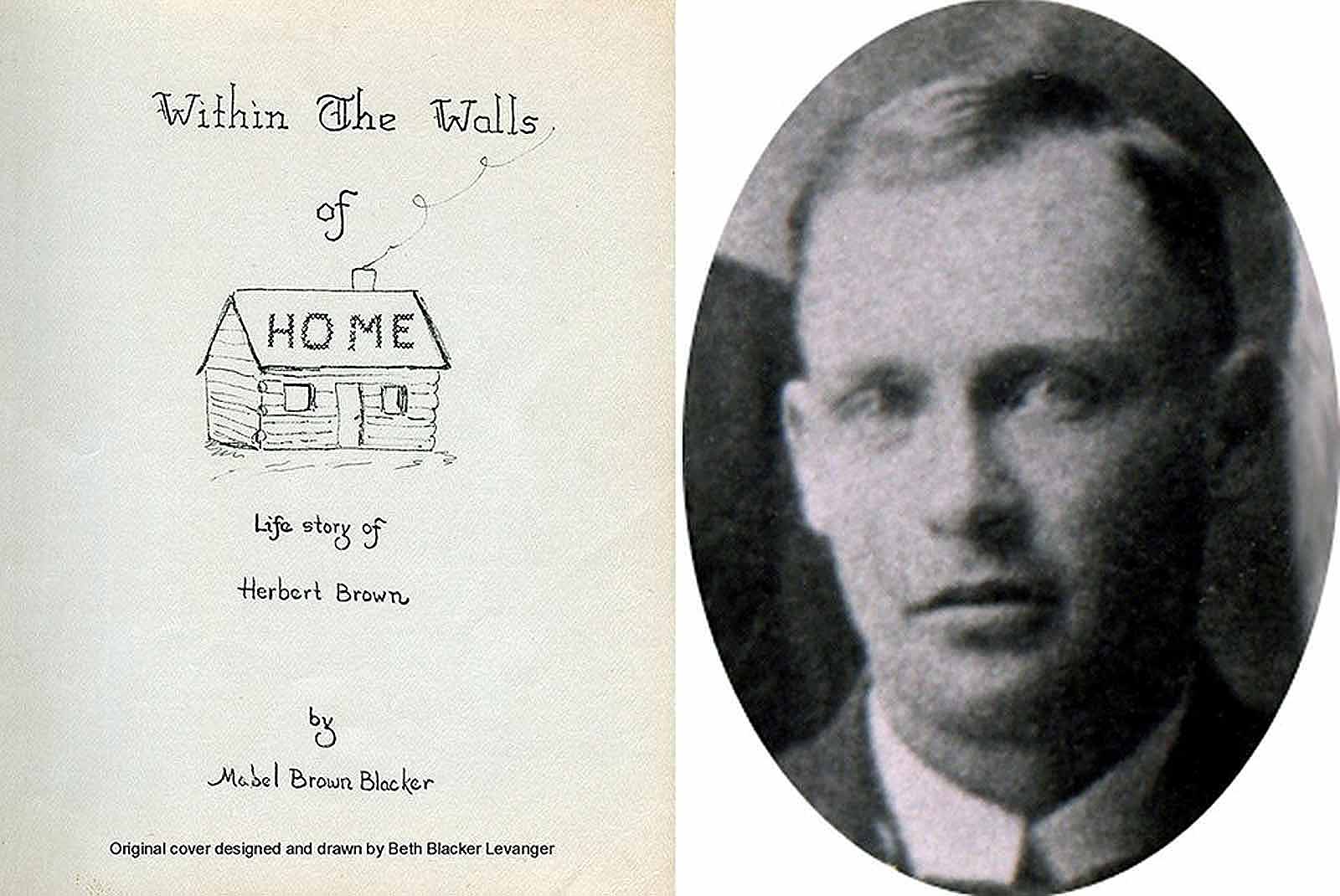

THE LIFE STORY OF HERBERT BROWN

By Mabel Brown Blacker

Edited by Ruth Blacker Waite

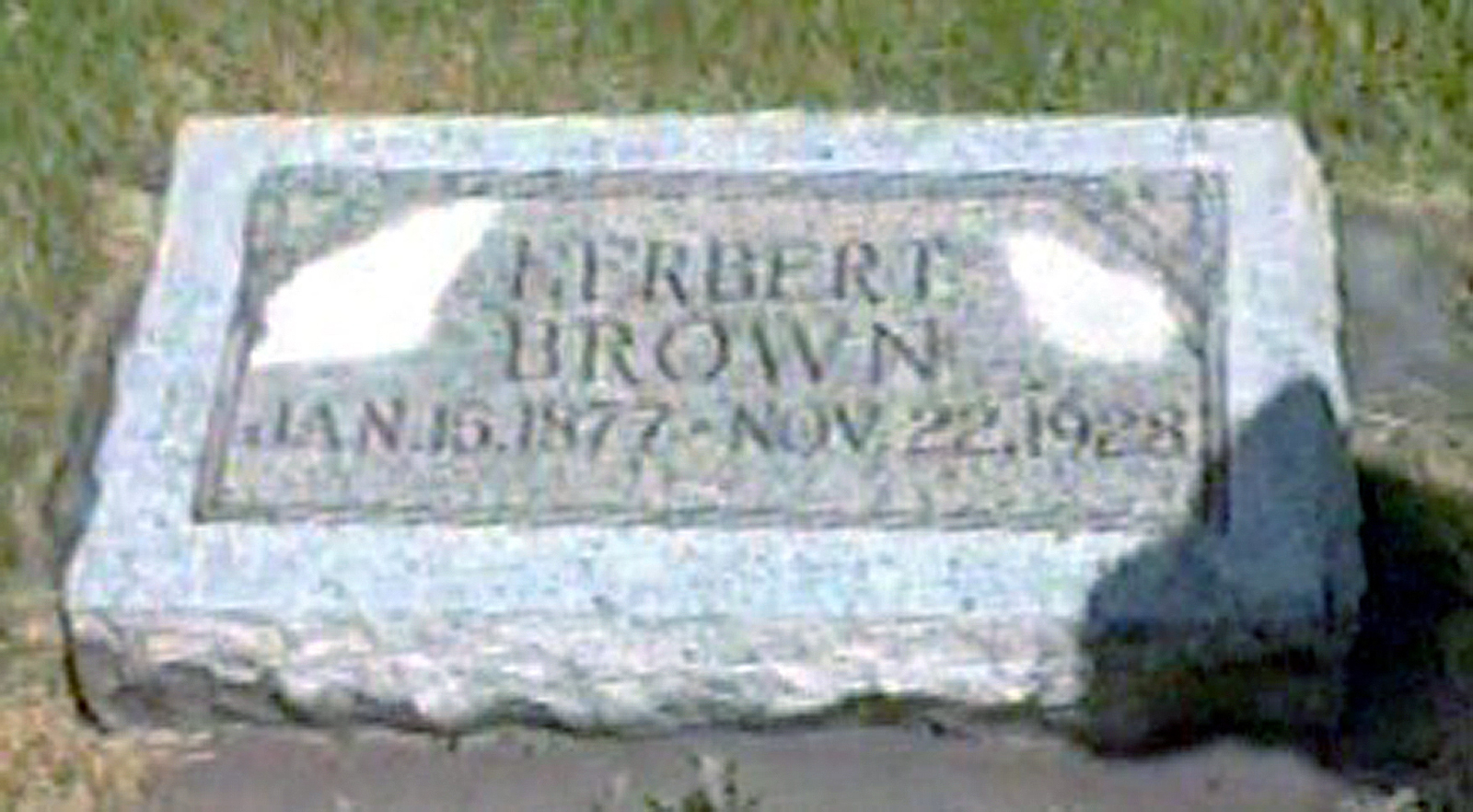

It was the 15th day of January 1877. The place was Almy, Territory of Wyoming. Most important of all, a baby was to be born. The warning signs had begun and preparations started for the event.

One of the grandmothers arrived after an urgent call and she took over the supervisory duties, capably and yet fearfully. She was well aware of the problems of birth. The bedroom was warmed, the bed prepared. The little gowns, shirts, binders, diapers and blankets were all taken from the dresser drawers, where they had been placed after lovingly being prepared for the occasion.

The doctor came in a horse drawn sleigh, carrying his usual black bag. Soon after his arrival the baby was born - a little blond boy with blue eyes.

As Harriet Bower Brown cuddled him in her arms, he looked up to see if he was welcomed. He was a beautiful child. He was hers to love and cherish, and indeed, he was welcomed!

The father, Adin Brown, was proud of this third child and second son. Little Martha, aged three, and William, one and a half, were excited about the baby. As they gathered around the mother's bed, they decided to call him Herbert.

That eventful day, closed as the winter night darkened on that little four room home - a home nestled in the mountains of western Wyoming in the valley of the Bear River.

That night could well have been one of those sublime winter evenings, seen so often in the West. The whole earth was white with snow; the sky a deep blue filled with many twinkling stars. As the moon arose over the eastern hills, the snow glistened like diamonds in the near-day brightness of moonlight. The lamplight streaming from the windows of the little house, and the smoke curling from the chimney portrayed a beautiful picture of home. Inside was love and peace. A baby had been born and all was well.

This was the home which welcomed our ancestor, Herbert Brown. It was the mountain home of his parents, Adin and Harriet Brown. All her life in England, Harriet had been told by her parents, "Someday we'll go to Zion - we'll have a mountain home."

Adin had also been born in England, but he didn't have the dream of Zion or a mountain home, for he hadn't joined the LDS Church until he was sixteen years old. Perhaps, however, when he was down in the dark coalmines where he had worked since he was nine years old, he had often wondered if there was a better life, and for this he had longed. Then his family joined the Church, and Zion and America became realities for him. This was to be for both of them. Their land, their home, their family and their Church! Their all, but far removed and so unlike their homes in England where they had lived all their younger lives.

England was old - old in history, towns, cities and government. Centuries had come and gone since the first people had arrived in England to live. Houses, ancient churches and cathedrals had been built and repaired, or built again with the passing of years. Farms and factories and mines had been begun and operated by men long buried in the churchyards they had made for their ancestors. This was true of the cobble stone streets and stone fences and walls. Their ways and traditions and methods of living had been the same for years upon years.

Almy, as all of Wyoming, was a new land, part of that west that had been almost wholly uninhabited except for bands of roving Indians and wild animals. Centuries had passed away since the land had provided homes, towns and farms for people long since gone. Perhaps during the short summer months, wandering Indians had visited the valleys, hunting in the hills and fishing in the creeks and rivers.

Buffalo herds, deer, wild horses, bear, wolves, mountain goats, and other wild animals had wandered over the countryside free and unmolested, except for Indians and the hostile association of each other. Smaller animals, beaver in the streams, squirrels, rabbits, skunks and all such animals, had all lived and raised their families and died. Coyotes had stood on the hills and had broken the night's silence with their cries, as they stood silhouetted in the moonlight.

Century after century had passed away as seasons had come and gone. In the passing years nature had religiously followed her regular pattern, despite the fact that no man was there to regulate or attend.

Finally, in the providence of a wise Father, the time for the populating of the West was to begin and the events leading to it started to happen.

Activity in the early West was slow at first, as a few hunters, trappers and explorers ventured further and further into the great, unexplored West. Years later, wagon trains followed the trails made by the explorers. Some were seeking for land and gold in California and Oregon, and then came Mormons, fleeing persecution to find peace in a new land, first by wagon trains and handcarts, and finally by the railroad.

As the Union Pacific Railroad gradually worked its way westward, their own explorers were sent in search of coal as fuel for the engines. Coal was discovered in two separate areas; one in what later became known as Rock Springs in Wyoming, and the other a little further west in Almy. Deep down in the earth, beneath the bare and desolate surface of the hills, treasured, black, carbonized, combustible coal was found.

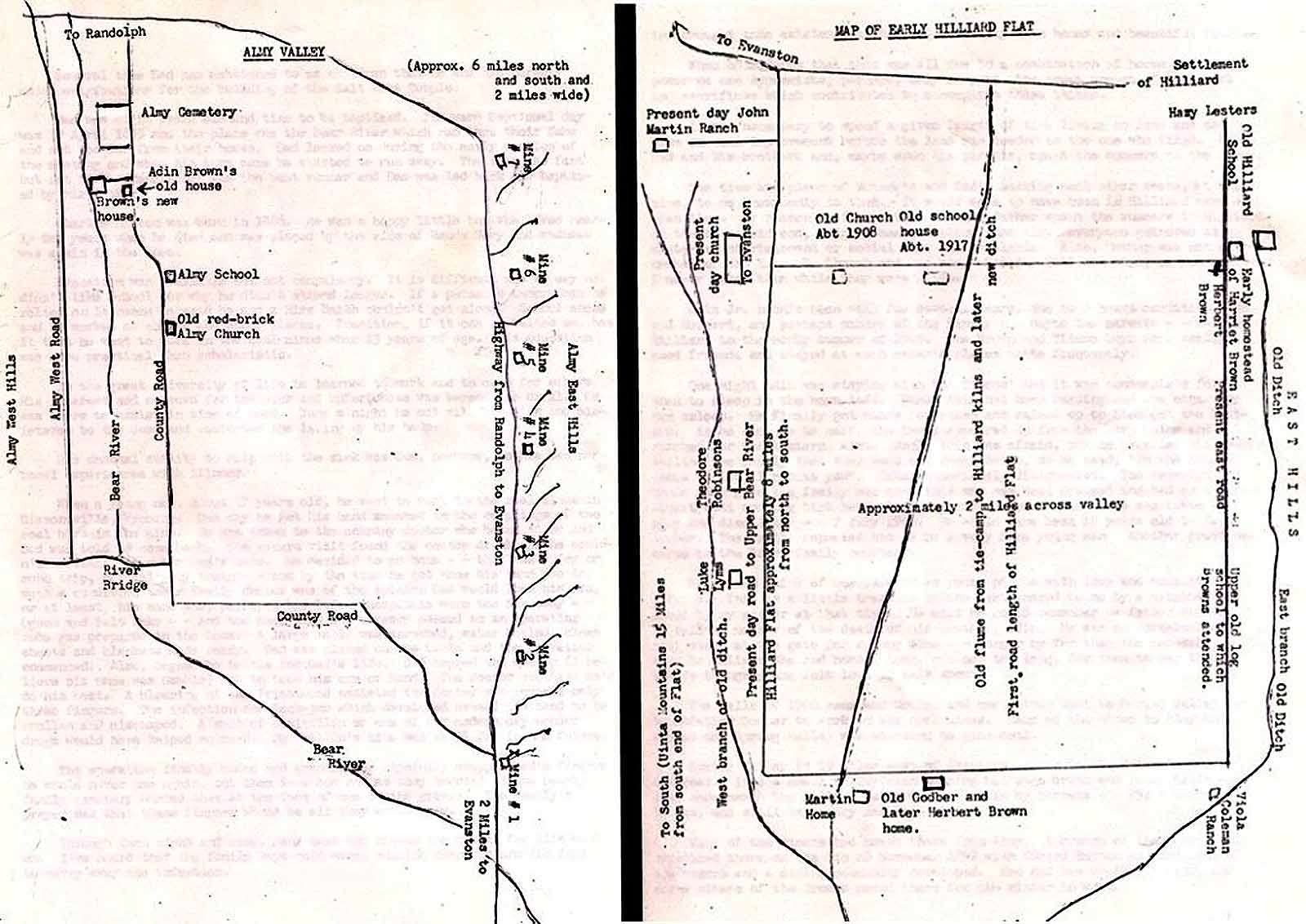

In 1868 in Almy, four or five miles north of what later was to be known as Evanston, coal mine #1 was opened. The place was named Almy for a railroad official, one Thomas J. Almy. Evanston became a railroad center eventually, with a roundhouse in which engines and rail cars could be turned about face, and thus Evanston and Almy became an important junction for the U.P.R.R. Both places were outgrowths of the railroad and each contributed to the growth of the great West.

The first coalmine was operated by the Rocky Mountain Coal and Iron Company. Most of the miners were LDS Church members newly arrived from Great Britain and northern Europe, who had joined the body of the Mormon Church and who were needing work. True to Church policy, as early as 1870, the Saints met in the "Old Wyoming Camp", and by common consent, appointed John Jolley to preside over them in a Church capacity. In 1871, Samuel Pike was officially called to preside over the Almy Ward at the time the ward was organized. At that particular time, Almy became the largest LDS ward in Wyoming. Evanston was organized as a branch of the Church in 1872.

Hannah Clark Brown

Hannah Clark Brown

The Browns and Bowers were in England preparing to leave for America, and Almy was ready to receive them.

Now to England to meet the family of William and Hannah Clark Brown, actually to the county of Derbyshire and to the ancient town of Alfreton, and within its confines to a hamlet called Somercotes. Here were our Browns and Clarks.

In May of 1870, William Brown, his wife Hannah Clark and his oldest children, including our ancestor, Adin, had joined the Church (Mormon). Twenty years before, the Clarks, excepting Hannah, had joined - one wonders now of the reason why she hadn't when other members of family did.

William and Hannah were the parents of nine children when the decision to immigrate was made. Martha Clark, Hannah's mother, and Martha and George Woodhouse, Hannah's youngest sister with her husband, also decided to come. Two of Martha Clark's older sons, Samuel and George, had been in Utah for many years.

Several years ago - 1976 - we visited Alfreton, Somercotes, and nearby places, and while there asked myself, "What made my people leave this beautiful place?" I was so entranced by its beauty, its grass covered green hills, its beautiful flowers and trees, its ancient quaintness and aged protection and security. "Why would they leave all this and travel far off to an unknown country?" Here was their home, their loved ones and friends and a way of life they had always known that gave them security and peace.

Alfreton Countryside

Alfreton Countryside

No doubt Hannah's brothers, Samuel and George, had encouraged them. Martha longed to see her sons and grandchildren whom she hadn't seen for a long time, or whom she had never seen in the case of some of her grandchildren. There was also the urge to "gather to Zion." Perhaps also, they desired a better life for their children.

Still, their roots were deep in England's soil and the "pulling up of those roots" wasn't easy - in fact, it hurt.

Hannah's trials began when she started to break up her home. What could she take with her? Just the bare necessities, just what she could cram into their trunks. The other things she must either sell or give away.

On that last night in England, the lamps burned late as friends and relatives came to wish them well, or to express doubts as to the wisdom of their venture. Many tears were shed by loved ones - mingled with their own. Surely, in this life they'd never meet again. The chains of love were strong, and their leaving left many aching hearts and lonely, empty homes.

Thus ended their life in England. The next day they rode the train to Liverpool, where the Church-charted steamship was waiting for them.

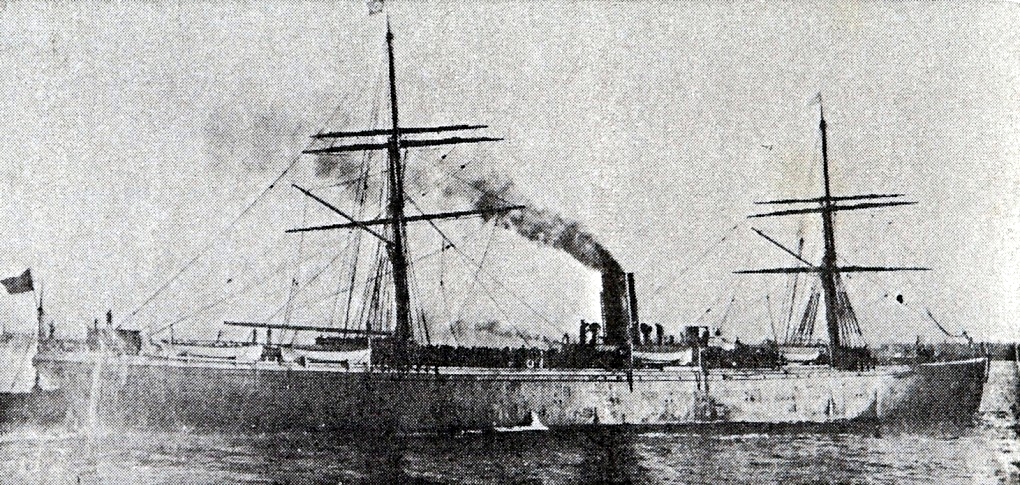

Wednesday, October 18, 1871, the Nevada sailed out into the Atlantic Ocean. Three hundred saints, under the direction of George H. Peterson, were on board including the Browns and relatives. England, which had been their home with her castles, churches, cottages and grand cathedrals, green hedges, rolling hills, cobblestone walks and streets, the mild, blue skies, their homes and friends, almost their all, faded slowly away in the distance. This great adventure had begun.

SS Nevada, Guion Line

SS Nevada, Guion Line

The crossing must have been an exciting, and never to be forgotten, but I have found no indication of a record of it. Church chronology states that the Nevada arrived in New York Harbor the 1st of November 1871 - making of it a journey of about thirteen days.

New York was the beginning of their railroad trip to the West. This must have seemed to them a big country, as day after day they passed towns, cities, and farms into the great plains of the midwest. Omaha, Nebraska, was not the end of the line for them as it had been for so many previous early pioneers. Our families continued westward on the shining, new rails of the Union Pacific. Soon, the snow capped peaks of the Rocky Mountains could be seen in the distance, and later, even the ground on the sides of the railroad tracks was white, as the train was to enter into the mountains of the west. This was the Zion for which they had left their all.

The train arrived in Utah the 11th of November 1871. From Liverpool to Utah, the trip had lasted twenty-four days. Compare that time to the time it took this writer, a great-granddaughter and granddaughter respectively to the heads of the families involved, just twenty-four hours to cover the same distance - this in 1976.

It is not known just where the travelers were met in Utah by their sons and brothers, but undoubtedly, it would have been at Echo or Croyden, up Weber Canyon. if not in Salt Lake City itself. We can but imagine that the reunion of Samuel and George, who had their homes in Utah, with their mother and sisters, was joyous. Undoubtedly, they had endured fears, doubts and periods of loneliness, but surely their meeting brought comfort and peace to their new homes.

My grandfather, Adin, left a few notes of his life, and among those notes he said they lived in Coalville, Utah, for six months - this would have been thru the winter of 1871-72. George Clark had settled and lived in Alpine, Utah, and Samuel lived in Coalville.

Six months later, the Browns learned that coal mines were starting to produce in Almy, Wyoming, and that miners were needed. Seemingly, it was an answer to their prayers and they moved to Wyoming. Great-grandfather William gathered together all his earthly possessions - mostly his family - and boarded the eastbound train for the short ride to Evanston. This must have been in late May or early June of 1872, for that would have been the six months Adin wrote about, since they arrived in America.

The train stopped at the small, new, frontier town of Evanston. Father William, mother Hannah, and all nine children stepped off the train. There stood our immediate ancestors, just themselves with all their worldly possessions in the trunks beside them. A few minutes later the train again started, whistled, gained speed and was out of sight around the bend of the track. The Browns were alone in a country so unlike their dear England so far away. Did they wish they could return? We don't know, for there was no use looking back with wishful thinking.

Their destination was to the Almy coal town about three miles away. There was a job for the men, a company house they could rent and a company store where they could purchase their needs. This was to be their home. Now, to the Bowers back in England. William and Martha Davis Bower had been born and spent most of their early lives in Brinsley, a small place in the parish of Greasley in Nottinghamshire, not more than five to seven miles from Somercotes.

William was seventeen years old when he first heard the Elders of the Mormon Church. He became interested, "took in the Millennial Star", a Mormon British publication, attended the meetings and was baptized the 12th of April 1852, at the age of nineteen years, nine months. The Church had been in England for only thirteen years when he first heard of it.

William kept a diary and I have copied parts of it for a separate story, but shall take the liberty to refer to part of it here.

He was very active in the Church doing missionary work and traveling from branch to branch. He married Martha Davis on the 26th of December 1853. Their first child, a daughter, was Penennah, who died as a baby. The next child, Harriet Hannah, was born the 23rd of September 1855. Harriet was to become our ancestor. After William and Martha were married, she accepted the gospel and was baptized by her husband before Harriet was born. As can be seen, this branch of our ancestral family belonged to the Church rather early.

This part of England belonged to the Nottingham Conference, later known as the Nottingham District and subsequently, the Nottingham Stake - the latter not for well over a hundred years from the times of William and Martha.

As William traveled from branch to branch and to the Conference meetings, he mentioned walking to hear the General Authorities who were in England during those years-Orson Pratt, Brigham Young Jr., Amassa Lyman, Charles C. Rich, Ezra Taft Benson, etc. He writes: Saturday, October 19, 1861, "I went to Codnor to a suppering of the Brethren. Ten of us sat down to a leg of mutton."

A very interesting sideline is that at one time in his traveling he went to Somercotes, Derbyshire, and traveled in his preaching with George Clark and James England. (others of our ancestors) He often mentioned the good times had as he met in the meetings.

During the years in England, he continued to work in the mines. He moved from Nottingham to Stavely in Derbyshire in December of 1851, and was called to preside over the branch there.

While in Stavely, he joined with others in forming a union for the protection of the miners. The mine owners objected and ordered all those who were active in the movement, to leave the company houses. Note his report on the occasion: Friday, November 16, 1866, "Started with 17 others with a wagon load of furniture from Stavely bound for Ilkeston (24 miles) drawn by human strength. We were ejected from our homes."

They stayed with relatives for months, but afterwards had to return to Stavely - "labor having surrendered to capital". Also added, "Brought my household furniture back and had a son born 1½ hours after we arrived".

During the same time, two of their sons, William, a few months short of four years of age, and Leonard, six months of age, died a month apart of scarlet fever, and were buried in Stavely. George and Alvin, other sons were ill for a long time, but survived. (In the original history, written by my mother Mabel Brown Blacker, she stated that the two children who died, were Christopher and Leonard. While looking over the family group sheet, I noticed that William and Leonard, died a month apart in 1864, but that Christopher, died in 1870 at age five. I believe this was a simple case of mixing up two of the children. RBW)

Harriet was baptized by her father at midnight, the 31st of December 1864, and confirmed the same night, which would have been the 1st of January 1865, by Thomas Saxton. Most baptisms were performed at night to avoid trouble.

During the summer of 1865, William went to night school, while Martha, his wife, never went to school and could never read nor write.

Now, in our story, twenty years had passed since William had been baptized, and those years were rich, productive years for the family. They had responded to the call of the Church, had married and had ten children while living in England, but had been called to part with six of them. These six were Penennah, William, Leonard, Christopher, Lucy and Elizabeth; each having died under the age of six. William had walked many miles preaching the gospel, singing and filling Church assignments. Martha was more of a homebody, but had also taken part, if only by her support. The family had longed for years to gather to Zion. Like the Browns and so many other families, the departure was not easy. Martha's parents were both dead, but Grandmother Bower wept bitterly - "I'll never see these grandchildren again."

William closed his diary thus: "Laboured well until my release on the 9th of June to emigrate to Zion with my family. We will set sail on the 12th day of June 1872 on the steamship 'Manhattan'. Landed at Castle Gardens on the 26th. Stayed there all night 27th. One o'clock in the next day crossed the river to Jersey where we got on the railroad cars for the West."

Family history states that they arrived in Almy, Wyoming, the 4th of July 1872. Church history, however gives the date of the arrival in Salt Lake City as that same day. In spite of this small discrepancy, the Bowers' trip from New Jersey by railroad, ended in Evanston. They then traveled those few miles on to Almy, where William started work in the mines.

Early Almy LDS records give this interesting information dated 9 July 1972: "William, Hannah, Adin, Alfred and Lydia Brown were rebaptized." Later entries tell of William Bower confirming some who had been rebaptized. (Rebaptism was a common practice in the early history of the Church. Ruth Blacker Waite)

The following was copied from this same record: "Minutes of a teacher's meeting of the Almy Branch at the school house held 2 Nov 1873: Elder William Bower opened the meeting. He and John Barton represented the first district and reported all well and the Saints were trying to live their religion".

Both the Brown and the Bower family records show the following: "28 September 1873, Adin Brown and Harriet married Sunday afternoon by Samuel Pike, branch president." Harriet was five days over eighteen years of age and Adin wouldn't be nineteen until December. Thus began a new generation of our ancestral family in Wyoming. No doubt the romance had begun in England at some conference or Church gathering there.

True, they were young in years, but life had taught them to assume responsibilities and they were prepared to cope. No doubt they rented a house from the coal company and started married life.

A few years later, their family consisted of two children, Martha and William. As the family started to increase, Adin and Harriet wanted to own a home of their own. They followed out their desire and Adin recorded in a notebook:

"This is to certify that I, Adin Brown, filed on one quarter section of land on the 15th day of February 1876 on the Bear River."

Land! Almost free for the asking - land no one had owned for centuries. How proud they were - poor coal miners from England! Now a few years later, they were citizens and land owners in America. The "magic wand" of the gospel had indeed enriched their lives.

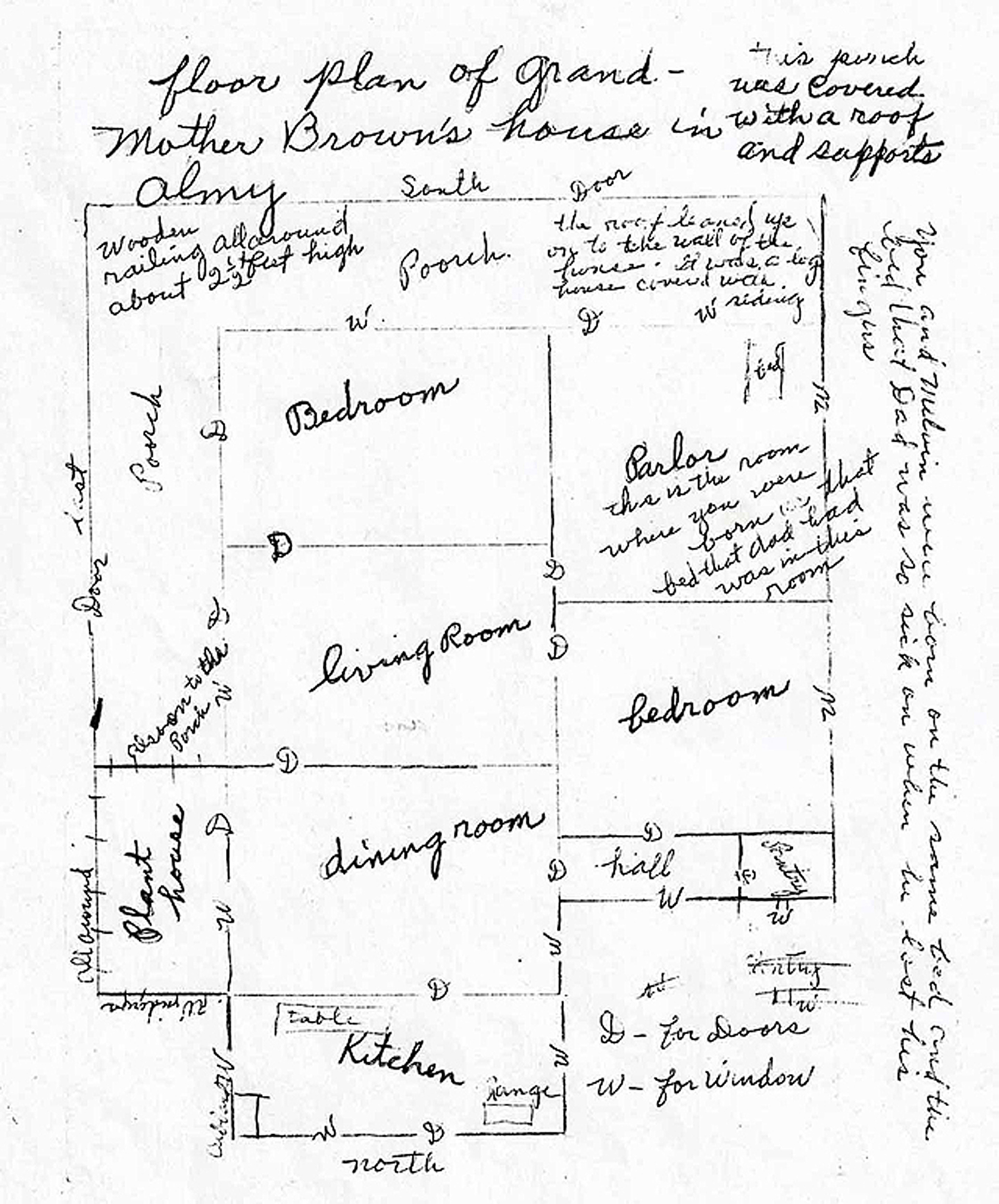

Family tradition states Adin bought and moved onto his land, a four-room house with a porch on the side. He placed the house by the side of the road and farthest possible from the Bear River. This was their mountain home where the family was living when their son and our ancestor, Herbert, was born.

Adin and Harriet had been married in a local church ceremony, but as the years passed they desired to be sealed for eternity. This desire was realized on the 26th of September 1879 in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City. Adin and his brother, Orson, took their wives, and according to the records were sealed by Wilford Woodruff, then a member of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, but who subsequently, on 7 April 1889, became the fourth president of the Church.

Ann Elizabeth Brown was born two and a half years after Herbert, and he lost his place as the baby of the family. The children laughed and played as happily as children always have.

The fifth child, a little girl, Maude Mary, was born. She came to bless the home for six weeks, and then she died leaving an unhappy and heartbroken family. Wanting to keep her close by, even in death, the parents chose a spot of ground on their own property, not far from their home, for her burial place. The grave was dug. Grandmother and others dressed little Maude for the last time in her best clothes, and placed her in a little casket. There was a little church service and the baby was buried. Often the parents would stop in their work and look at the little grave with tears in their eyes - this was in August 1881.

Hannah Clark Brown's broken headstone, repaired since this picture was taken.

Hannah Clark Brown's broken headstone, repaired since this picture was taken.

Fall came and Christmas passed and a new year came which brought another sorrow to the Brown family. Hannah Clark Brown, mother of Adin, died January 25, 1882. She was a young woman, not yet forty-seven years old. She was the mother of thirteen children - twelve still living to mourn her passing. Her oldest, Ann, who had died and was buried in far off England, was to meet her on the other side. Hannah had brought nine of her children to America and had given life to three more here. They would have greater blessings and opportunities than she had ever had.

The family decided to bury her close by Maude Mary. The snow was shoveled away, a grave was dug in the hard frozen earth, and Great Grandmother Brown was sadly, but lovingly laid to rest.

This was the beginning of the Almy cemetery. This place became dear to the hearts of the Brown family as one by one, in the years to come, others of the family would be laid to their final rest to await that beautiful morning of the distant future. The family continued to grow as Adin Jr. and Frank came into the group. A large family is usually a loving family, one that learns early to love and care for each other and to assume responsibility. Early these children were taught to work, and Dad (Herbert) was always busy.

Adin and Harriet Bower Brown Family, 1890 Back: William 15, Martha 17 Middle:

Harriet, Adin Jr. 9, Frank 7, Adin Sr. Front: Ettie 6 mo, Annie 12, Herbert

14 (This is probably the last picture taken of Herbert with all fingers on both

hands)

Adin and Harriet Bower Brown Family, 1890 Back: William 15, Martha 17 Middle:

Harriet, Adin Jr. 9, Frank 7, Adin Sr. Front: Ettie 6 mo, Annie 12, Herbert

14 (This is probably the last picture taken of Herbert with all fingers on both

hands)

I recall him saying his mother had him help with the laundry. She had one of the push-pull machines and he'd work at that until he was tired. Then he'd have one of the other children take his place and his mother would say, "While you're resting you can tend the baby." There was always laundry and babies. Herbert learned to care for chickens, gather the eggs, carry water in and out, bring in coal and wood, and carry out the ashes. As he grew older, cows were to be cared for, including the milking, and there were horses to care for. Grandfather Adin had a religious home. The family was always active in the church. It is reported that if a boy started to smoke (women didn't in those days) Grandpa would say, "Let's you and me go outside for a talk or a walk." Several times Dad has mentioned to us children that he and his parents made contributions for the building of the Salt Lake Temple.

Dad was eight years old and it became time to be baptized. The ward baptismal day was 19 April 1885. The place was the Bear River, which ran thru their farm and not too far from their house. Dad looked on during the early portion of the meeting, and when his turn came, he started to run away. The race was fast, but not far. Grandfather was the best runner, and Dad was led back and baptized by his father.

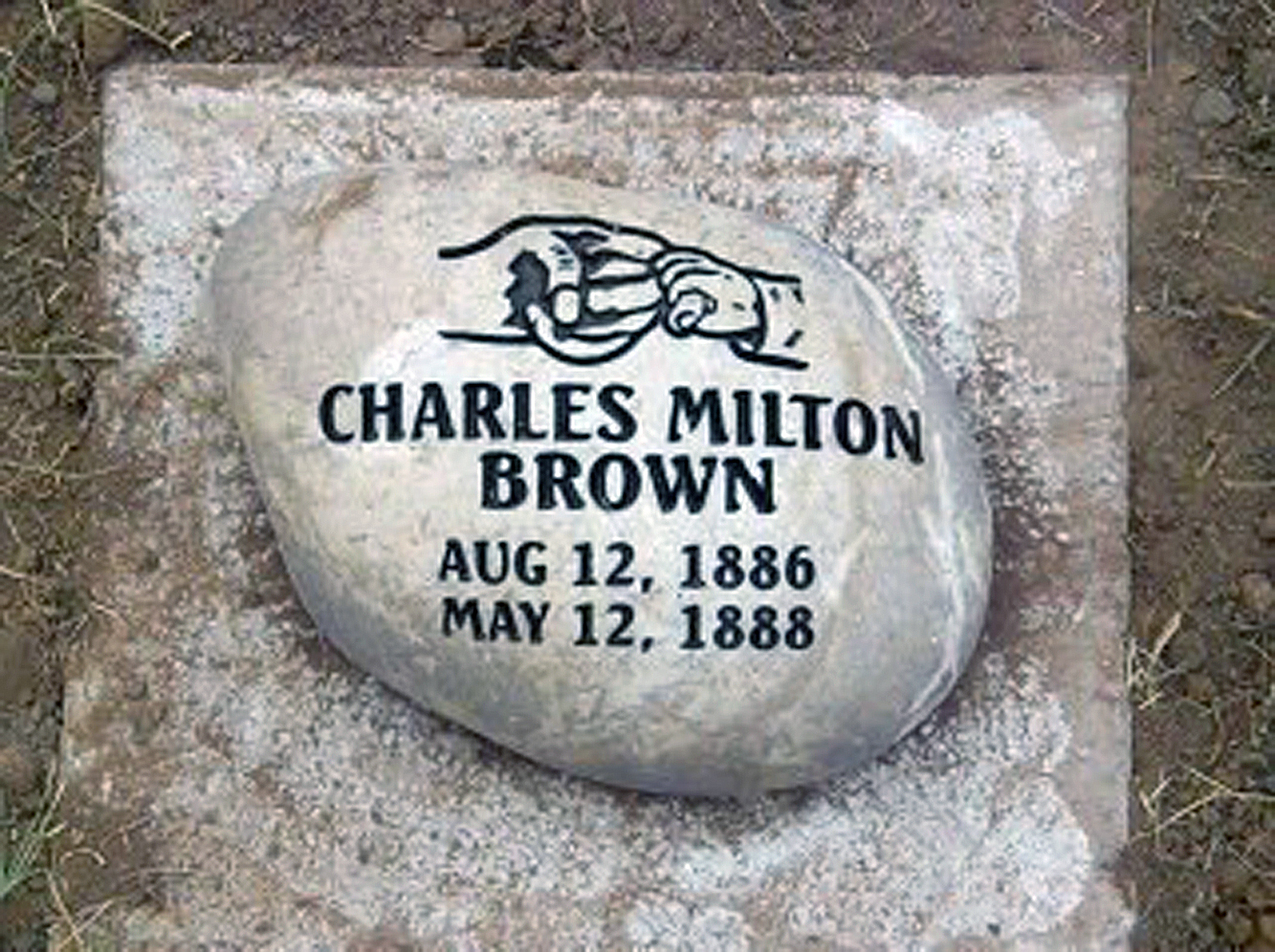

Charles Milton was born in 1886. He was a happy little boy who lived nearly two years, when he died and was placed by the side of Maude Mary, and sadness was again in the home.

Education was available, but not compulsory. It is difficult now to say why he didn't like school or why he didn't attend longer. If a person's memory can be relied on, it seems he said he and a Miss Smith couldn't get along. School ended for him, and he worked at chores and in other places. Tradition, if it can be relied on, has it that he went to work in the coal mines when thirteen years of age. His education was more practical than scholastic..

In the great university of life, he learned to work and to care for others. His interest and concern for the sick and unfortunate was beyond the usual. He was there to assist in time of need. Many a night he sat with the sick, ministered to the dead, and comforted the living by his help.

Herbert Brown

Herbert Brown

His unusual ability to help with the sick was due, perhaps, to his own personal experiences with illnesses.

When a young man, about seventeen years old, he went to work in the coal mines in Diamondville, Wyoming. One day, he got his hand smashed in the couplings of two coal cars in the mine. He was taken to the company doctor who bound it up, and Dad was told to come back. The return visit found the doctor drunk and he couldn't or didn't take care of Dad's hand. Dad decided to go home - this was a day or more trip, partially by train - and by the time he got home, his hand was in such a condition that their family doctor was of the opinion Dad would lose his arm, or at least, his hand and perhaps, his life. Hospitals were too far away - Ogden or Salt Lake - and too much time had already passed, so an operating room was prepared in the home. A large table was scrubbed, water boiled, clean sheets and blankets made ready. Dad was placed on the table and the operation commenced. Also began the battle for Dad's life. Dad begged the doctor (I believe his name was Gamble) not to take his arm or hand. The doctor promised he'd do his best. A blessing of the Priesthood assisted the doctor who removed only three fingers. The infection and the lock-jaw which developed, caused the hand to be swollen and misshapen. A shot of penicillin or one of our modern day wonder drugs would have helped so much. Penicillin's time was still far in the future.

The operation finally ended, and grandmother carefully wrapped Dad's fingers that he would never use again, put them in a box, and hurried to the nearby family cemetery, where they were buried at the foot of one of the graves. The family's prayer was that these fingers would be all they would bury.

Through that night and many, many days and nights, the battle for life went on. I've heard that the family kept cold water running down his arm for days, to carry away the infection.

Glove knit for Herbert Brown by his mother Harriet

Glove knit for Herbert Brown by his mother Harriet

The family's prayers were answered, but the adjusting commenced and went on for years. Tears of gratitude - and tears of regret and sorrow were shed by those who loved him then. Those of us who loved him later saw not the disfigured hand, but a hand of love that guided us along the path of life. One of my choicest possessions is a knitted glove made by my grandmother to keep his hand warm in the cold weather.

Living close to the river, Dad and his brothers learned early to swim. A swimming hole close to the Brown home was used by all the boys in the neighborhood. One summer day Dad and his father were hauling hay from the field, and some boys were in the river shouting and playing. Suddenly Dad became aware that the sounds had changed to alarm and he said to his father that he thought the boys were in trouble. His father didn't think so, but Dad finally ran over to see if all was well. As he arrived at the river, he saw three or four boys trying to help one in the river. Dad dived in and soon had the boy on the bank, and he and grandfather were able to get the boy breathing again. We kids would have Dad tell us this story many times. To us he was a real hero. One day, years afterward, when Dad had passed away, Mother and I met this boy, now a grown man, of course. He took our hands in his, and with tears in his eyes, thanked us over and over again for Dad saving his life. He said, "I was going down for the last time and I knew I was drowning. Then this young man pulled me out and saved my life."

Two other children joined the family. Harriet Helen, who was called "Ettie", and Lyman.

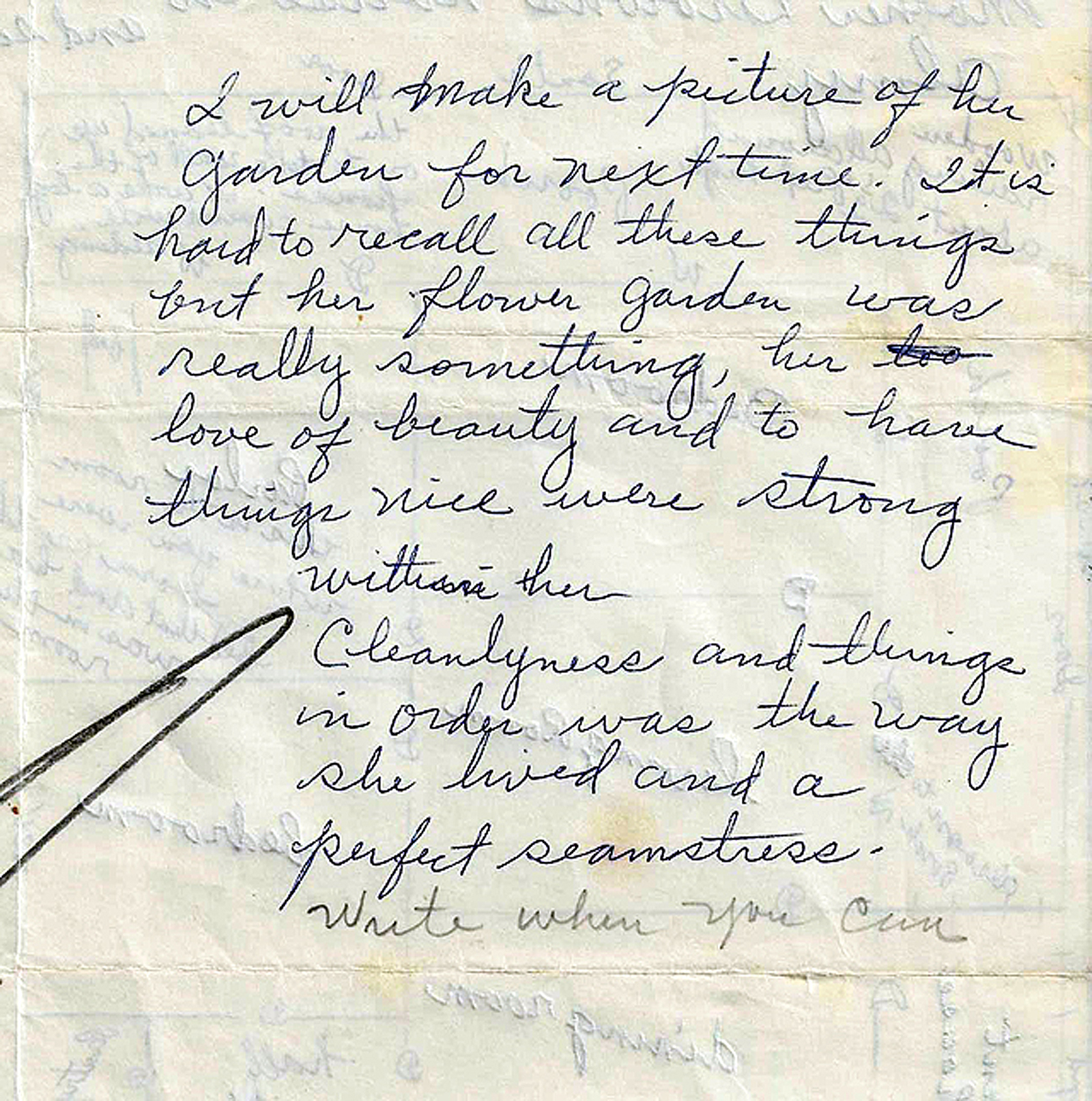

The years passed, the family continued to grow, and the small house wasn't large enough for them. Grandfather decided to build a larger house, closer to the river and further from the county road. This was a beautiful and spacious house and was built mostly by Grandfather and his sons.

Grandmother Harriet had been apprenticed to a well-to-do woman in England, and had learned to be a good housekeeper and to like lovely things. I recall the home years later, surrounded by green lawn, which was closed in by a white picket fence, flowers of many kinds and bushes of yellow roses. I see this lovely home in my memory. There was a little stream of water running about halfway through the lawn with a little arched bridge over it.

Grandmother loved flowers and she had one room on the east side of the house where she grew her beautiful houseplants. The living room was beautiful, as I recall, the most beautiful place I'd ever seen until then. There was a floral carpet on the floor, pretty curtains at the windows, and hanging from the center of the ceiling was a chandelier lamp with long glistening prisms. When the lamp was lighted, they glowed with all the colors of the rainbow. The coal and wood heating stove, with its isin-glass window, showed the red flames glowing inside. It was altogether really something to be admired. (Isin-glass was special glass that could withstand high temperatures, or perhaps, thin, transparent sheets of heat-resistant mica. Ruth Blacker Waite)

I realize that from the time Grandfather started to build, that years passed before it was the beautiful home that I knew as a little girl. There was a special bedroom with a really beautiful, hardwood bedroom set. This was special for occasions when they had special guests, births and serious illnesses.

During the years, many of the family first opened their eyes and saw the light of this world, while others closed their eyes for the last time, to be opened in the light of another world.

The house became a home by daily living. Joys and sorrows came to those who lived there - life isn't always easy, but it is beautiful. Laughter of children and grandchildren echoed through the rooms and hearts. The growing boys and girls dreamed the dreams girls and boys dream, as they prepared for parties, dances, dates and life. Prayers were said, the gospel taught, instructions and corrections were given as needed. Each child leaving the home left an emptiness, that seemed to bless and sanctify the home.

A picture on the wall of one room in the house always intrigued me as a little girl - one Man walking on the water, and trying to help another man who couldn't. This home was like all good homes - a haven on earth for all the family.

Martha Hannah Brown Nisbet oldest daughter of Adin Ebed and Hannah Harriet Brown

who died just short of age 20 at the birth of her first child.

Martha Hannah Brown Nisbet oldest daughter of Adin Ebed and Hannah Harriet Brown

who died just short of age 20 at the birth of her first child.

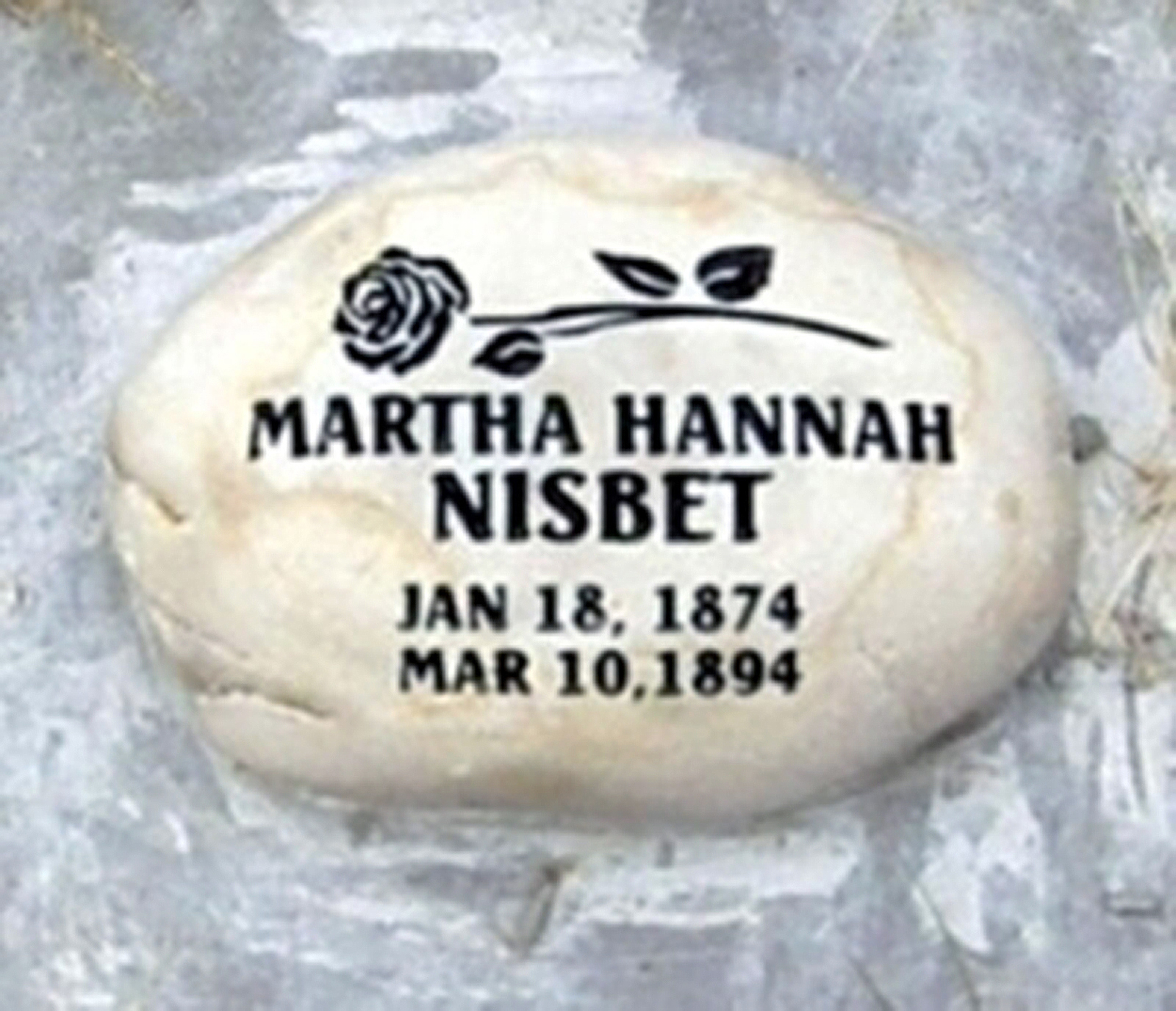

Martha Nisbet's Tombstone

Martha Nisbet's Tombstone

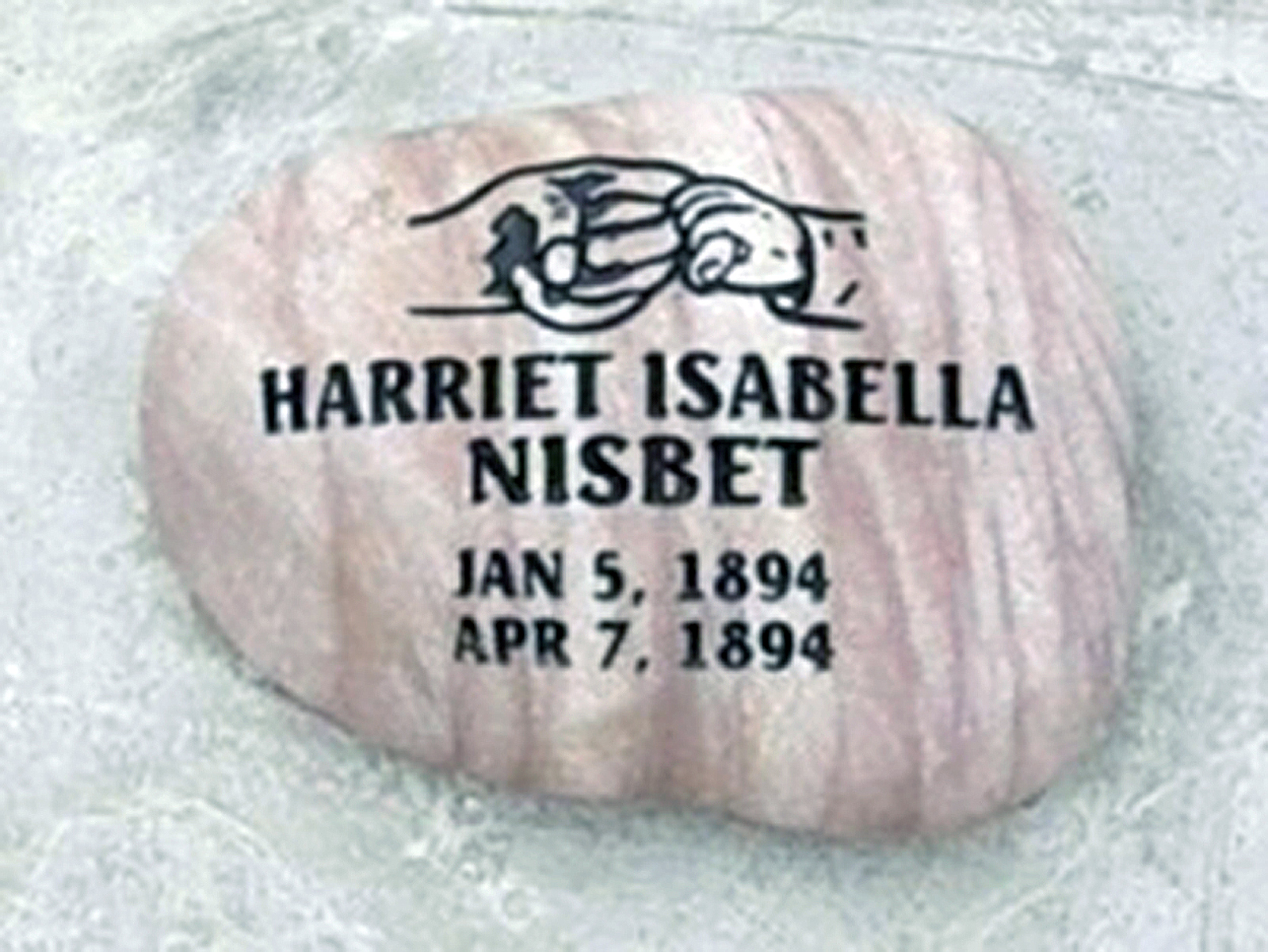

Martha's Daughter's Tombstone

Martha's Daughter's Tombstone

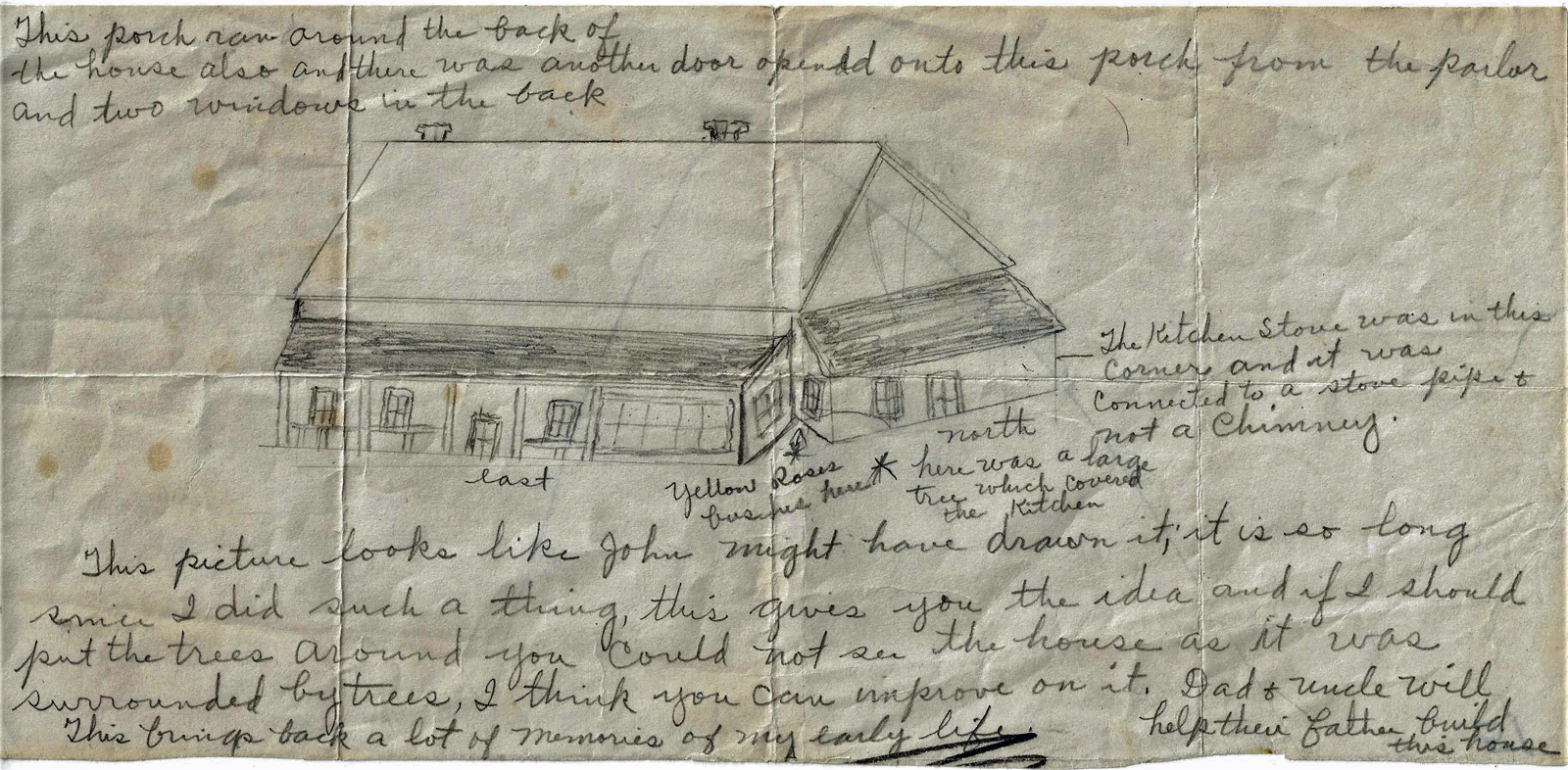

Martha had grown into a beautiful, quiet and charming girl. She was the first to leave the home. She married William Nisbet in the Logan Temple on the 29th of March 1893.

Life seemed to offer so much for them as they anticipated a happy life together. Their baby daughter was born the 5th of January 1894, and was named Harriet Isabella for both of her grandparents. The price of the baby was high - the mother's life. Martha never recovered from the baby's birth. She died the 10th of March 1894, two months less than 20 years of age.

Martha's death almost overwhelmed the family. She had been a second mother to all the children - her brothers and sisters - and she was her mother's right hand. Another grave was added to the little cemetery and as they gathered around her for the last time, they wondered why anyone so young and lovely should die. Another sorrow came less than a month later, when the baby joined her mother. She died the 7th of April 1894. Another little grave added to the family plot.

Almy had grown to be a community of coal mines numbering from Mine #1 to Mine #7. It appeared to be a prospering community and had an excellent future, with over 5,000 people living there. Then disaster struck on the 20th of March 1895. Mine #5 exploded at about 5:45 pm. The normal routine of the mine was broken by three blasts, which caused flames and dust to be shot out of the mouth of the mine. The blasts sent out timbers and boards and caused a great amount of damage on the outside of the mine. All the men who were inside the mine were killed. The explosion came but a few minutes before the day crew was to leave the mine, and prior to the time the night crew was to enter. Many and many are the stories told of the catastrophe, including the reports that some of the usual day crew had felt impressed to not work that day, or of how some had left early.

Few families in the community were not affected. I don't know where my father or his father and brothers were at the time, however, Uncle Willard Brown (Adin's younger brother) was one of the sixty-two casualties. He was a young man and left a family - a wife and seven small children. As soon as the mine was considered safe, volunteer miners (I believe my Dad was one) went down and brought out the dead. The coal company provided caskets for the dead and prepared the bodies for burial and then the dead were taken to their homes to await the funerals. Such was the common practice during this period of time. Some of the dead were shipped out of town, some to Evanston, and to other places for private funerals.

Funeral services were held in the Almy Ward red brick church house for thirty-three Latter-day Saints.

From the Deseret News - the Church Salt Lake newspaper - of that date I copied a little information. Wilford Woodruff was president of the Church, and Joseph F. Smith, Franklin E. Richards, Seymour B. Young and Edward Stevenson were sent to the funeral to represent the Church. Before 2 pm the caskets began to be brought into the (then) large meetinghouse. The caskets were followed by the respective mourning families. The people were seated in rows outside and the doors of the church house were left open.

Bishop James Bowns conducted the services. President Cluff, stake president, and the General Authorities who were present, sat on the stand. The choir leader was James Hood. In song and sermon the sorrowing Saints were comforted as best as possible. In one song which was sung, "God Moves in a Mysterious Way", the last verse answered in part the "why":

Blind unbelief is sure to err

And scan His words in vain.

God is His own interpreter

And He will make it plain."

After the services, the caskets were again placed in the wagons and taken to the waiting graves, most of them being in the Almy cemetery. Willard Brown was placed close by the grave of his mother who had preceded him death. Sorrow and sadness again was with the Brown family.

Adin Brown had filed on the land in Almy in 1876, and had made his home on it. Their boys were needing to find employment, and the fear of the mines may have made our grandparents seek more land. Some of their friends, especially the Birds and Titmuses, were homesteading land thirty miles south of Almy at Hilliard. The Browns filed on one hundred sixty acres in Grandmother's name. This was situated on the east of the Hilliard valley on the north-south road, where the church and school were later built.

The land went from the road back to Sulphur Creek. Herbert filed on land from Sulphur Creek up on the hillside. A nice, log house was built close by the road, with barns for the horses and cattle. A nice garden spot was set out, and of course, rocks and sagebrush were cleared to produce the hay and pasture lands needed.

The first Hilliard ditch carrying water from the Bear River up at the top of the "flat", as the area was called, had been dug, but the water rights had been for only a certain amount of water. That amount wasn't enough to carry the additional water, which this group of new homesteaders needed. The new people formed a new ditch company known as the Bear River Canal Company. The earlier ditch company was the Hilliard West Side Ditch Company. The first ditch, thru the years, became known as the Old Ditch and the last was known as the New Ditch.

The records of the Bear River Canal Company yield this information: "15th September 1898, Adin Brown and Joseph Bird surveyed the canal from the Bear River down to the acres of land the canal would serve." The records also state that on July 9th, Adin was a Notary Public and treasurer of the company. On the entry for the 11th of January 1900, Adin, Harriet and Herbert are listed as stockholders. Herbert and Harriet continued holding stock for several years until other people bought their holdings.

My grandfather, James Godber, had assisted in making the Old Ditch and my father, Herbert, had assisted in making the New Ditch, both of which carried the life-giving water to the dry lands, which within a few years of their construction, brought into existence a thriving community with homes and beautiful fields.

When considering that this was all due to the combination of horse and manpower we can appreciate, perhaps, only in part, the great amount of hard work and sacrifices, which contributed to the accomplishment of these things.

It was necessary to spend a given length of time living on land and to make so much improvement, before the land was deeded to the one who filed. Hence, Dad and his brothers, and maybe even his parents, spent the summers on the ranch.

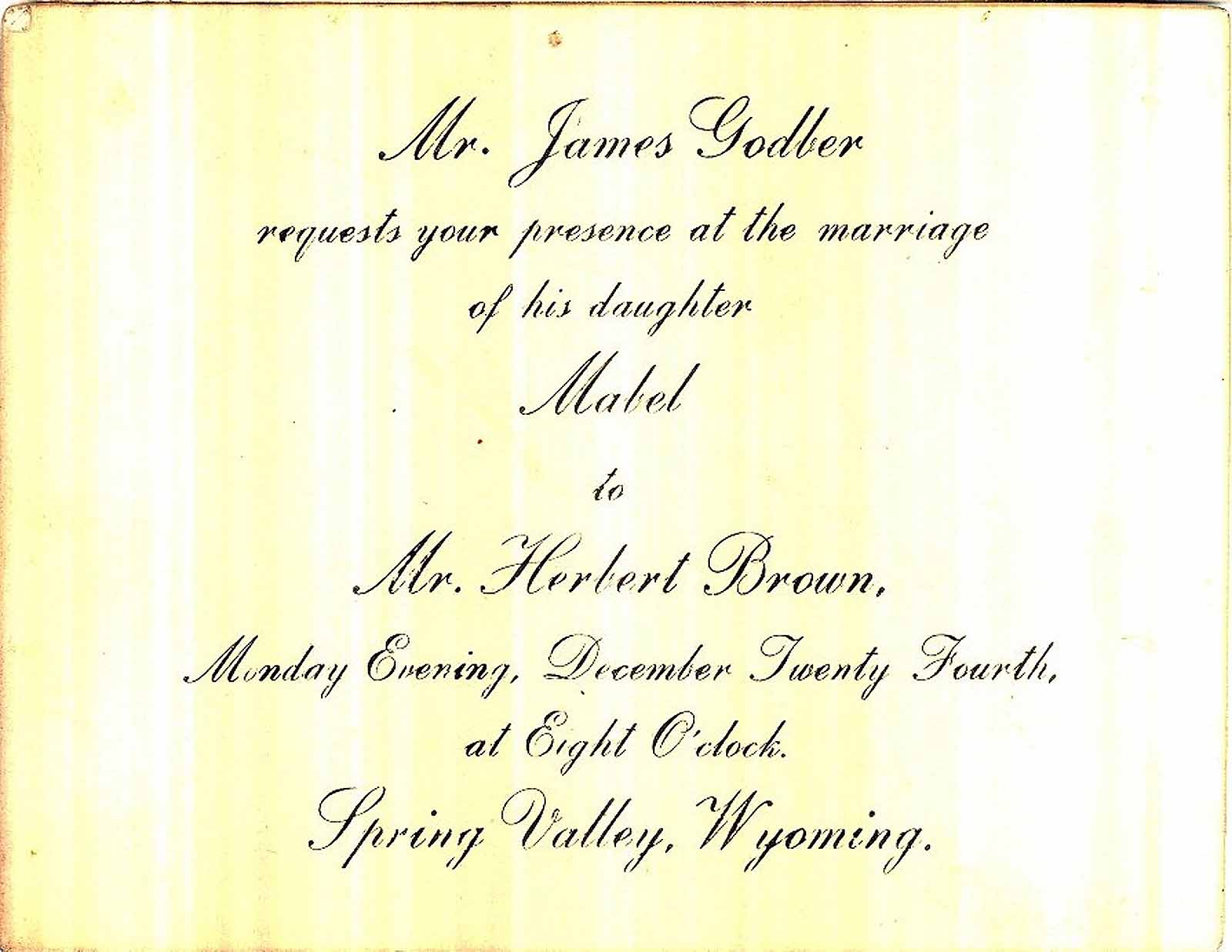

The time and place of Mother's and Dad's meeting each other seems, at this time, to be known only to them. It would seem to have been in Hilliard more so than Almy. My reason is that Mother and her father spent the summers in Hilliard on the homestead, and because it was a smaller place than Almy, everyone gathered at whatever entertainment or social that was available. Also, Mother was not a member of the LDS Church and Dad was. Someday I'll ask them, or you can. I never asked them while they were alive.

Adin Jr. hadn't been well for several years, due to a heart condition. He and Herbert, and perhaps others of the family - maybe the parents - were at Hilliard in the early summer of 1900. The Brown and Titmus boys were really good friends and stayed at each other's places quite frequently.

Adin Ebed Brown Junior

Adin Ebed Brown Junior

One night Adin was staying with the Titmuses, and it was commonplace for them to sleep in the barn loft. Uncle Adin had been reading and the other boy was asleep. He finally got ready for sleep and raised up to blow out the lantern. As he did so, he said, the Devil appeared up from the barn below and reached for the lantern, also. Uncle Adin was afraid, but he recalled his mother telling the family that you need not fear Satan, so he said, "In the name of Jesus Christ, I rebuke you." Satan immediately disappeared. The description Uncle Adin gave the family was that this man was well dressed and had on a Prince Albert coat and a big tall hat. This experience upset Adin so much, that he was taken to Almy and died later -7 July 1900. He would have been eighteen years old in September. The family reported him to be a very fine young man. Another grave was added to the Brown family cemetery.

We seldom think of our parents as young people with love and romantic affairs. This is a little treasure of the past shared to me by a neighbor, who lived by my mother at that time. He said he could remember my father coming to tell my mother of the death of his brother, Adin. He was on horseback, and they stood at the gate for a long time - longer by far than the time necessary to deliver the sad news. Long, but not too long for them to say the little things young folk love to talk about.

The fall of 1900 came, and Mother and her father went to Spring Valley for Grandfather Godber to work in the coalmines. Many of the mines in Almy had closed, and Spring Valley was starting to mine coal.

Spring Valley is nineteen miles east of Evanston, close to the Union Pacific Railroad. It's a small valley with nothing but sagebrush and rocky hills with coal underneath them. Water was hauled in by barrelsat the cost of twenty-five cents a barrel. It was, and still is, a dry, desolate place.

Many of the miners had moved there from Almy. A branch of the Church was organized there on the 8th of November 1899, with Edward Burton as president of the branch, and soon a mining community developed. Dad and his brother, Frank, and maybe others of the Browns moved there for the winter to work.

This new mining community was known as Spring Valley. New buildings, such as houses and "out-houses", which were the outdoor "plumbing" of the day, were being built by the coal company, for the use of their employees.

Dad and Mother made plans to be married in December - 1899. Grandpa Brown went to visit his sons in Spring Valley, and to assist with the plans for the wedding. One evening he visited Mother and her father there. The night was dark and he wasn't fully aware of his way back to his sons' place, due to the changed environment. He had a serious mishap of falling into an unfinished hole, injuring himself and losing consciousness. It was later determined that he had been in that state for about seven hours, before he was found the next morning. When he hadn't returned, the family went searching for him. He had been seriously hurt. Their account of him was that "his heart had been permanently 'dislocated'." He was never well again.

Mother and Dad were married Monday evening, December 24, 1900 at 8 o'clock, by the presiding Elder of the branch, President Edward Burton. Mother had a beautiful, long, blue satin dress with a high neck and long sleeves. The dress was trimmed with white braid and ruffles. Grandfather Godber had a dressmaker in Evanston make it. With her dark hair, she was a beautiful bride. Dad always liked nice clothes and in his new suit he himself, looked handsome.

They had a reception and received some lovely gifts - some of which are yet in some of our homes. Mother kept a piece of their wedding fruitcake in her trunk, which, as I recall, was as hard as rock, years later.

Dad and Mother lived in Spring Valley for a few years after they were married. Alice and Violet were both born there. Dad has said he made more money in Spring Valley mine than anywhere else, but the coal gas was so intense, that he suffered from severe headaches and sometimes had to go to bed for relief.

Alice once told me about what she could remember living of in Spring Valley. The folks would take the train, which stopped there, and go to Evanston to shop, or to visit the family in Almy. Alice said, as they got off the train on their return trip, they would walk a short distance up the hill to their home. She would carry a few packages, for she was a little girl of four or five. Dad would carry the suitcases and whatever else, and Mother carried baby Violet. As I recall, they left the mines each summer to return to their ranch in Hilliard, which they were developing.

Surely these were years of happiness and rich experiences for Dad and Mother but, because I know so little, I write but little.

Grandmother Brown's folks, the Bowers, lived in Almy for a few years for two more of their children, Rose Ellen and John, were born there. They also lived in Croyden, Utah, to be near their good friends, the Hopkins, whom they had known in England. In Croydon, three more children were born, Samuel, Martha Elizabeth and Heber Henry.

Martha, the youngest of Grandma Brown's brothers and sisters - fifteen in all - often visited us in Ontario, Oregon, and told us so much of the Bower's life in Croyden. Typically true of the English, the Browns and Bowers were very superstitious. William Bower's mother was very sad when he left England with his family. She wept bitterly and said, "I'll never see any of my dear grandchildren again." She never did.

Aunt Martha, who married Joseph Garner, told me this story of her mother's experience upon returning home one evening just before dark. She saw a woman that reminded her of her mother-in-law. She was some distance and couldn't see the woman's face. The woman knocked at the front door and as no one was home, no one answered. The woman went to the back door. Great-grandmother hurried as fast as she could, but when she got to the back door, no one was there. Several weeks later, word was received from England that great-great-grandmother Bower had died and counting back to the unusual appearance of the strange woman, they decided it was the night she had died and that she had come to see them. You may draw your own conclusions.

Great-grandfather, William Bower, wasn't as faithful as he had been in England, so far as the Church as concerned, after he came to America. Before his death, he decided to repent and go to the temple - but time for that has passed. In those inactive years, some of his children wandered away from Church activity also - some still aren't in the Church. My only reason for mentioning this - from activity to inactivity - is for it to be a reminder - and perhaps a warning - for us all, me especially; for several times in my life I've made a hurried retreat back to safety. It's easy to find excuses and blame others and maybe others are to blame, but the results are ours to regret. I'm not aware of all his problems, nor do I know the people nor the conditions, so I'm not in a position to judge.

He was a good man and she was a good woman. Their lives had been hard and difficult, and yet, not knowing our way of life, they were happy. They brought part of our line of ancestry to America and set our feet on the right track.

He died on the 21st of July 1890 of a fatal heart attack, as he went out to feed the pigs. He was buried in the Croyden cemetery beside two of his children. Great-grandmother spent much time with her daughter, Harriet, in Almy. Some of her sons, George, William and John went to Lava Hot Springs to live. She died there on the 16th of May 1908, but is buried in Croyden.

Several years ago, in the twilight of an autumn day, we - my husband, Loyn and children, Mary and John and myself - visited their graves on the hillside outside the town of Croyden, Utah. Parking the car by the gate to the cemetery, we entered and searched among the graves for the Bowers. We could hear the motors of the passing cars on the highway about a mile away.

Finding the graves, we stood in silence and as we were standing there, a big jet airliner sped across the sky far overhead. These were sounds that, in their lifetime, they never heard. Their graves were well kept and well marked. The sun was going down behind the hills, and in the oncoming darkness, the cooing and chirping of the birds added to the peace and quiet of their graveyard sleep. As we left their little cemetery, closing the gate behind us, I felt, for the first time, a closeness to them I had never felt before.

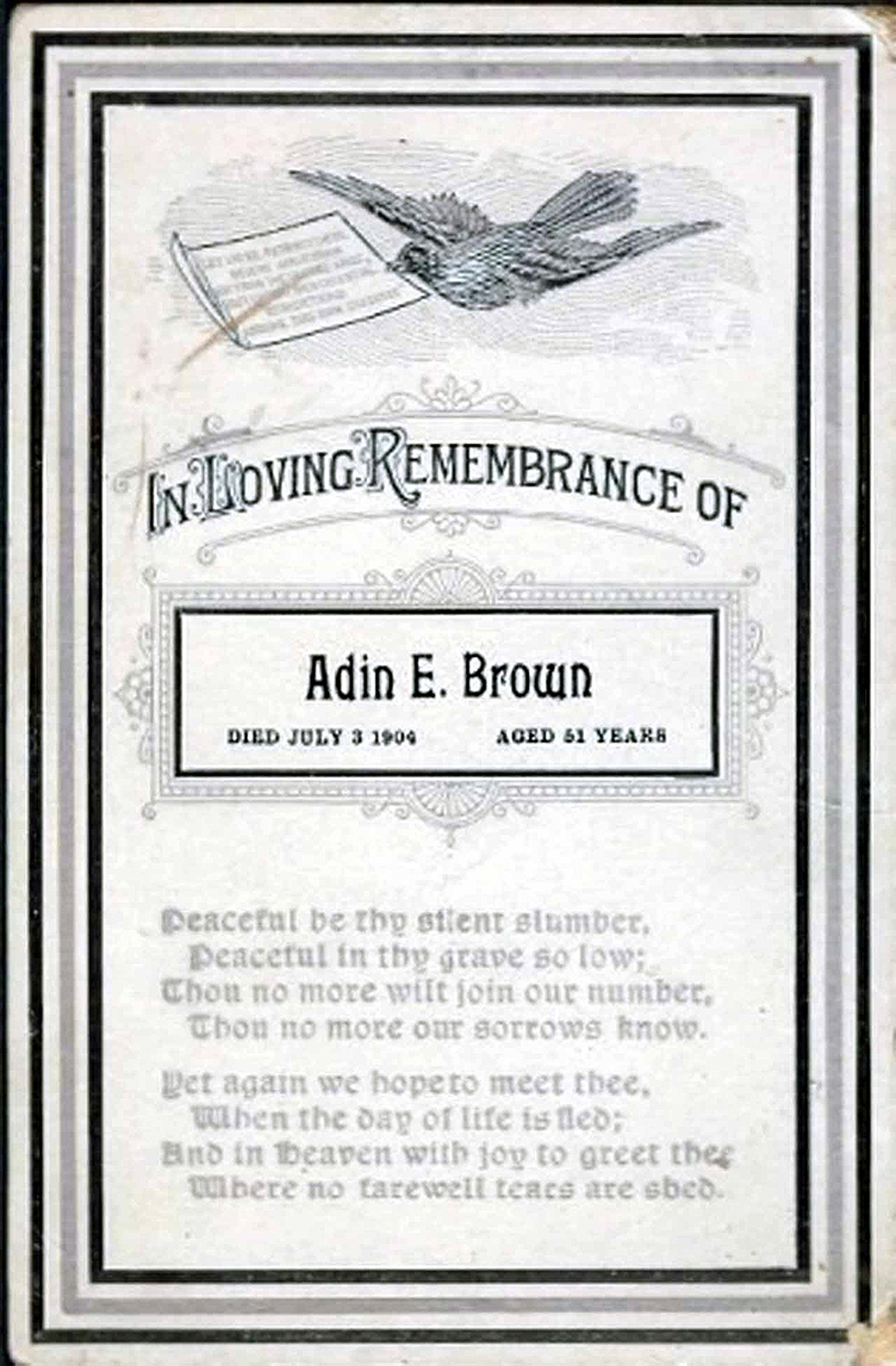

Grandfather Brown had been ill since he had been hurt in the late 1900. He had by 1904, been in Almy for thirty-three years. These had been rich and growing years. He had married, raised a family, made a home, taken his place in building the community and served in the Church he loved. He reported serving as president of the Young Men's M.I.A., in the Elder's quorum presidency, and as a teacher in the Sunday School organization. Years ago someone gave me the date of 18th June 1882, as being when he was set apart as superintendent of the Almy Ward Sunday School, which position he held for eighteen years. His counselors were Edward Burton and Joseph B. Martin. He loved young people!

I've heard that a familiar sight on the 4th and 24th of July celebrations, would be Grandfather at the head of a march. He would be pounding on a tin can or a bucket as the children lined up to get their customary sack of candy, nuts and an orange. About 1902, he was set apart as 2nd counselor in the Almy Ward bishopric, by Charles Kingston of the stake presidency. William Beveridge was bishop.

As the years went by, since he had been hurt, he grew steadily worse. All these years he had suffered great pain. At last he became bedfast, and being a large and heavy man, it was difficult to move him. An apparatus was fixed so he could move himself. He was cared for by kind, loving members of his family and by good friends.

It was in the latter part of June 1904, that Dad and others were staying with him one night. Grandmother was resting in another room. The night wore on, and Grandfather became worse and told Dad and the others that he was dying. Hurriedly, Grandmother was called and she urged him not to leave her. Because of his efforts, and the administration of the Holy Priesthood, Grandfather rallied, but he gently chided her and the others, and begged them not to hold on to him for he was ready to die and felt he could endure the pain no longer.

The family including Grandmother, yielded to his desire, realizing death was the only cure for his pain, which he had so patiently endured. A few days later - 30 June 1904 - he quietly left this mortal life.

His body lay in peace for a few days in his beloved home that he had built and made a place of beauty. Family and friends gathered for his funeral, which was held in the red brick Almy church house he had also, helped to build, and which had become a part of his life. Words of comfort and praise were given to this great man, still young, not yet fifty years old. A horse drawn hearse carried his body to the cemetery. Nearly twenty-three years before, he had dug a grave on this very site for his baby daughter, which grave was the commencement of the Almy cemetery. The tears shed now were not his, but for him. This was the 3rd of July 1904.

Grandfather, in this life, I never knew you, but I'm proud to be your granddaughter. I shall love to meet you some day.

Grandfather Brown's illness and death called for the help from their married children's families, and it has been reported that Dad and Mother always helped Grandmother. No doubt this is the reason Dad and Mother spent the summers at the Hilliard homestead. Dad also had his own land close by.

Alice told me once that they lived the summers at Dad's and Grandmother Brown's places at Hilliard. She said there was a nice house and barns and that the land had been cleared so there was a garden and some meadow.

I've never tired of hearing the folk tell of being in Almy at Grandmother Brown's, and on returning back to the Hilliard house finding that lightning had struck it, and if they had been home, they would have been killed. A lot of damage was done to the house, but there had been no fire. It seems there had been either several shafts of the lightning at once, or the house had, otherwise, been hit twice. One shaft seemed to have come up from the floor, for it laid parts of the floor on the bed and blew out some windowpanes and laid them unbroken several feet away from the house. Another shaft seemed to have come down the chimney - the stove lids had been blown off - with one lid having flown across the room and hitting the side of the cupboard with such force that it left a permanent imprint on the cupboard. The nails that held the cupboard shelves all melted, and the contents were on the bottom together. Soot from the stove and chimney was all over the house. Cleaning up was a job, and perhaps, this is one reason Mother was so afraid of lightning. Grandfather Godber, still alive, of course, had been in Almy with them.

Spring Valley closed in 1905 and in the fall of 1905, the folks, Grandfather Godber, and Uncle Frank Brown and family went to Glencoe to work in the mines for the winter. Glencoe was a mining town between Kemmerer and Cumberland. The town is no more. The men worked in the mines and all seemed well. Grandfather Godber became ill in January and pneumonia developed which resulted in his death the 30th January 1906, as he was sitting propped up in his beige rocking chair. He had seemed to have been improving in the morning, but during the day he became delirious and thought himself back in England and was talking to family and friends he had known so long ago. Before evening, he had gone to join them on the other side. What a reunion that must have been as he was reunited with his wife and seven children and other dear ones that he had been parted from for so long. All the heartaches and longing loneliness was over for him, but for Mother and Dad and his two grandchildren it had just begun. His body was shipped from Kemmerer to Evanston, for burial in the Evanston cemetery by the side of his brother, Isaac.

One of the many legacies left to us was how he would often repeat to his daughter, "Mabel, just don't murmur."

The funeral over, Dad and Mother returned to Glencoe to finish the winter work only to face another problem. Uncle Frank, Dad's brother, was ill of typhoid fever and died the 16th of February 1906, just over two weeks following the passing of Grandfather Godber. Uncle Frank was a young man, not yet twenty-two years old. He and Aunt Elizabeth (Boam) had been married when he was only seventeen years old. He left his wife and two sons, Raymond and Adin Brown. Another trip to Evanston, and on to the Almy Cemetery. with another grave in the Brown Family plot.

Spring came and Dad and Mother returned to Hilliard from Glencoe. The trip in the wagon had been long and the roads no more than trails over rocks, along ruts and thru the sagebrush. The wagon contained all the furniture, clothes and dishes they had used during the winter. The small, unfinished, log home, which Grandfather Godber had built, stood silent and deserted. This was the place where Mother and her father had lived and made their home, and as she turned the key to open the door her father had locked months before, she was welcomed by the memories of their earlier lives together, - a sad day for Mother, as she loved her father so much. Alice, several times, has told me that she remembered how Mother cried.

Frank Brown

Frank Brown

It was also a sad time for Dad, as he and Uncle Frank had spent much of their lives together. Dad seemed to love his brothers and sisters and loved to visit them. The time for sorrow however, was past - the future must now be faced. There were decisions to be made, problems to be solved and lives to be lived.

Grandfather's house was too small for the folks, so in time another house was started, but when the well was dug, the water didn't have a good taste. Another location was chosen and on it was built a two-room log house, a large kitchen and a bedroom. A well was dug by hand and rocked all around. The water here was clear, cool and had a good taste. A wooden frame was built around the well, so whoever was drawing up the water by rope and bucket, wouldn't fall in. A little house was built over the well to protect it, and to keep kids and animals from falling into it. In later years, if a child was ever lost, the first place we looked was down the well. Milk and butter were kept cool in the summer when placed on a rock shelf a little way down the well. No refrigerators in those days!

The summers were spent clearing the land - digging and burning sagebrush, hauling rocks, making ditches, planting grasses and clover as the land was cleared. I believe Grandfather had planted some grain and alfalfa, and Dad did also, but those didn't seem to produce successfully, so clover and timothy were planted which grew with the native grasses. Grandfather had used a scythe to cut his limited crops. I still recall it hanging on the wall of the barn. Dad used it to cut weeds or small amounts of hay, but he bought a mowing machine and a rake, and progressed from hauling by wagon to the derrick, and then to a stacker.

Great-grandfather, William Brown, died the 10th of July 1906, in Almy and was buried by the side of his wife, Hannah, who had died twenty-four years before. He had lost in death six of the thirteen children. Five had died as adults, leaving small children. He had remarried, this time to Mrs. Abigail Scothern, and lived a short time in Providence, Utah. They were later divorced and he finally moved back to Almy where he lived with his son, Uncle Orson, until he died at about seventy years of age. I wish I knew more about him, but I realize his life wasn't very easy. He brought his family to America so we could have a better life than he had known while in England, and, perhaps, than he had known while in America. I love him for that great sacrifice for and in behalf of his posterity.

The Almy cemetery, which had first started when Maude Mary was buried, and added to when Hannah Clark Brown died, became, as the years went by, a burial place for the community. In fact, Grandfather Brown deeded it to the Church for that purpose.

Graves were dug by the families and friends of the deceased. Dad was helping dig a grave for someone, and as of now, I'm not sure of the date, nor the name of the person for whom it was being dug. When nighttime came, the grave wasn't finished, so Dad agreed to finish it as there wasn't much more to be done. In order to do so, he arose early the next morning while it was yet dark and went with a lantern to the cemetery to finish it.

Soon he heard a loud sizzling noise and looking up out of the grave, which was being illuminated by a big ball of light, which lighted up the sky. It came from the west and disappeared over the hills to the east. He finished the grave and returned to the house. I have loved to hear Dad tell this story and marveled at his bravery. His daughter wouldn't have been there in the first place. I do not remember that we ever learned what the falling object was that crossed the sky - probably a bright meteor or falling star as we call them.

The folks spent the winter of 1906-7 in Almy, for Dad to work in the mine and to help Grandmother Brown. Mother had been interested in the LDS Church for several years. She had attended the meetings and had associated with its members. She had read the Book of Mormon, believed it to be true and desired to be a member. Although it was wintertime and the river was frozen over - there was no indoor baptismal font in those days - Mother wanted to go ahead. A trail was made to the river, which was close to Grandma's house, the snow tramped down, a fire built and a hole cut into the ice. Family, friends and Church officials gathered on the banks of the Bear River. Two little girls watched with concern as their mother removed her coat and shoes, and walked toward the river wearing only her dress. She continued right into the water as she was lead into it and put under the water by Uncle Oscar Sessions. It was a relief when Mother came up from the water and was back on the bank where Dad had warm blankets to wrap her in and take her back into the house. Baptisms are always special, and for the family, this baptism was no exception. Alice and Violet, and I suspect to the rest of us who were not yet born, it was an extra, extra day for now we would have the privilege of being Latter-day Saints. And this was not only for us, all of Dad's and Mother's descendants, but, also for her ancestors for none of them had the privilege of hearing the gospel in their lives. Mother had a very special mission.

I joined the family in Almy in Grandmother Brown's extra special bedroom on the 20th of May 1908 and was named Mabel May Brown. Two years and a week later, Dorothy was born in the little house at the end of the lane - this in Almy, also, the house where Dad was born 30 years before. Dad now had a ranch and four girls and he needed a boy to help us.

Early recollections of our home are dear to us. As I recall those early years, I know that our lives were very simple. Perhaps by some we were considered poor. There is no doubt of that by the standards of today - 1982 -, but we always knew we were loved by our parents. Dad spent time playing with Dorothy and me and I'm sure he had done the same for Alice and Violet years before. We rode many a mile on his foot as he sang to us. One song I recall, "If I'd Be Jock Tampson." He made tops for us from Mother's empty spools of thread, and would cut willows with lots of leaves for the tails of the stick horses, which we actually "rode" for many miles. From green willow branches, he made real whistles, which would work when we blew on one end. He also made molasses candy for us. We would ride on his back when we persuaded him to get on his knees, and he would buck us off when he got tired. After so much of this fun he'd put us to bed.

Mother always cooked and sewed for us and took special care of us when we were ill. She was always concerned and worried about us. They both had but a very limited schooling and their desire was that we have a good education. This desire almost became an obsession with them. We had to go to school, and no foolishness nor misbehavior would be tolerated. They made many sacrifices so that we could have opportunities and they were distressed when we didn't do our best.

Dad was very good in times of sickness and death. Many times he would sit up all night with sick folks - doctors and hospitals were unavailable so many times. Many times he would help prepare bodies for burial. He was concerned about people. He would have been a good doctor if he had the opportunity. We liked to have him be with us when we were sick.

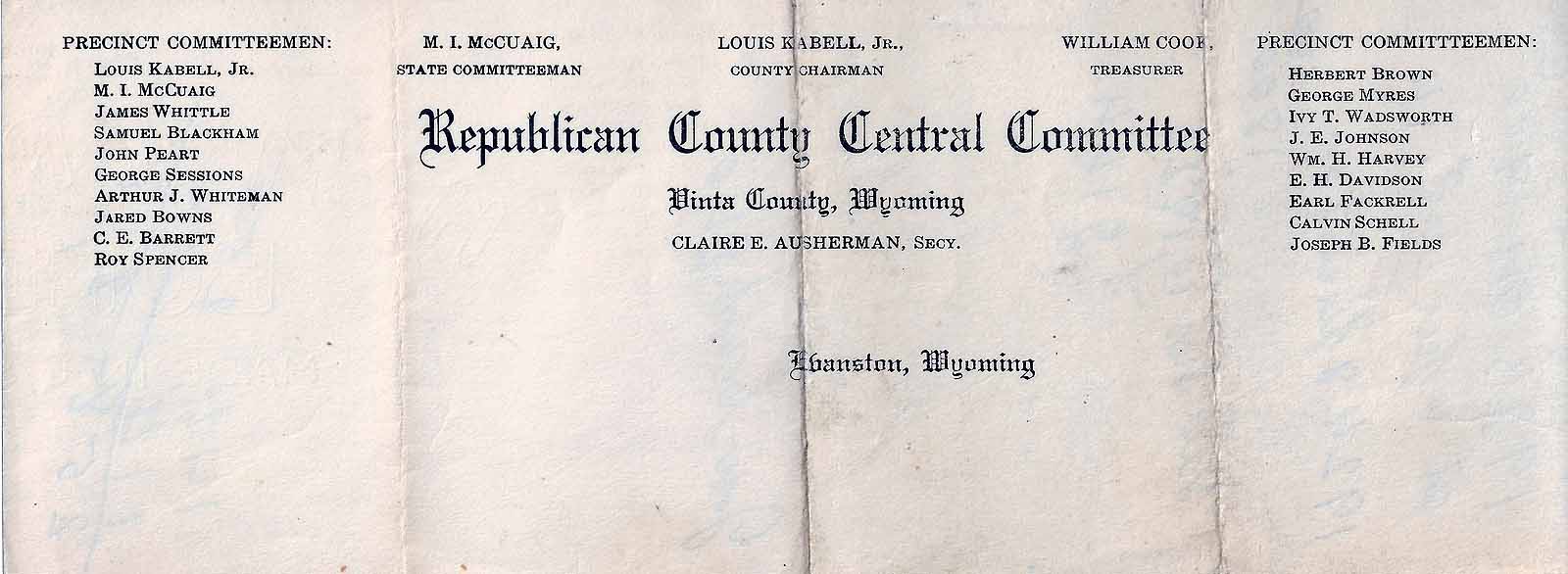

Both Dad and Mother were always active in politics. They were Republicans, like their fathers. But Dad's mother, brothers and sisters were all Democrats. A story has it that Grandfather Adin Brown was the candidate on the Republican ticket for road supervisor and Grandmother refused to vote for him. Dad always worked at the elections and many times he would go to Evanston to get the ballot boxes. He would then return them with the election results, which required two round trips for a total of eighty miles traveled for each election. In those days, most of the traveling had to be done by horses.

Letterhead of Republican Central Committee showing Herbert Brown as Precinct

Committeeman

Letterhead of Republican Central Committee showing Herbert Brown as Precinct

Committeeman

He also served as precinct committeeman for the party. Those were the days when politicians visited all the precincts. Dad would have charge of the Republican one, so quite early we got involved in political rallies and elections. Those were the days when electricity was not yet available to us, so kerosene lamps were used. I can still see Mother preparing the lamps we would take to the rally. The politicians would expound long and loud on the campaign issues. Afterward there would always be a dance. A luncheon, provided by the women would be served - sandwiches, cakes and cocoa, usually. The issues and the politicians have long been forgotten, but the memories of those political rallies in the old Hilliard Ward church house are still dear to my heart.

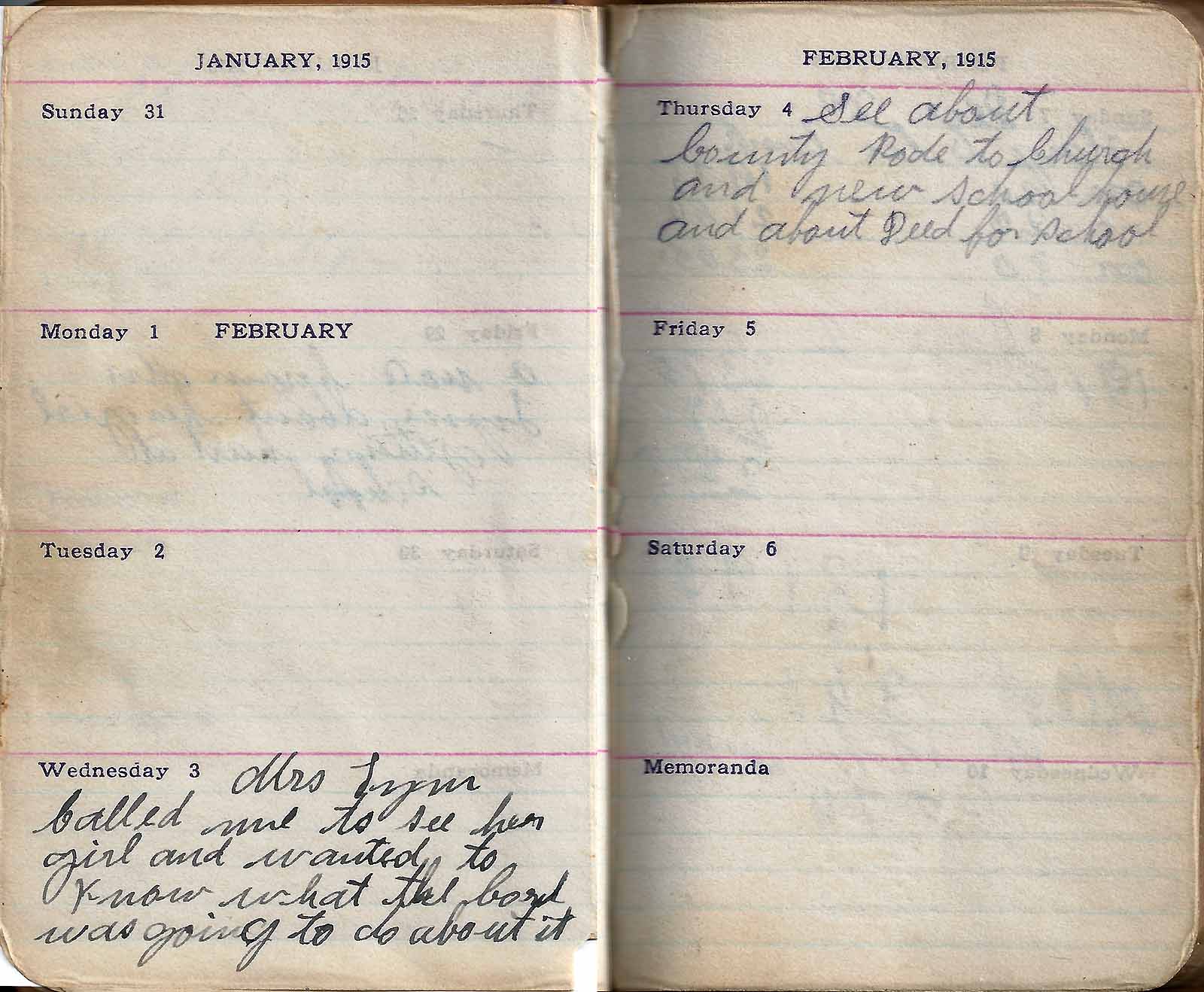

Dad always attended annual ditch meetings, and he and Mother supported the school board meetings. District #1 was a large district and many and loud were the opinions voiced. He also served for many years on the school board.

Harriet Brown center, left son Lyman, right grandson, Adin Benjamin

Harriet Brown center, left son Lyman, right grandson, Adin Benjamin

In 1913, Grandmother Brown went to Superior, Wyoming, to spend Christmas and the New Year holiday with Uncle Will, who was working in the coalmines there, and also with friends who had once lived in Almy. The time was spent in visiting and Grandmother liked to do that. New Year's Day and evening had been especially festive, but it was too much for Grandmother who had suffered a stroke several years before. During the night she became ill and died before morning - the 2nd of January 1914. We didn't have a telephone, but one of our neighbors did and we received the news of her death from them. Dad wasn't at home - he and two other neighbors were baling hay some miles away. He came home upon receiving the news and we left for Almy. The trip in the sleigh was long and cold and it was way into the night when we arrived at Aunt Ettie's (Harriet) and Uncle Oscar Session's. They were living in the house at the end of the land - Grandmother's early home. Aunt Ettie came out to meet us and I can still hear her sobs mingled with my father's.

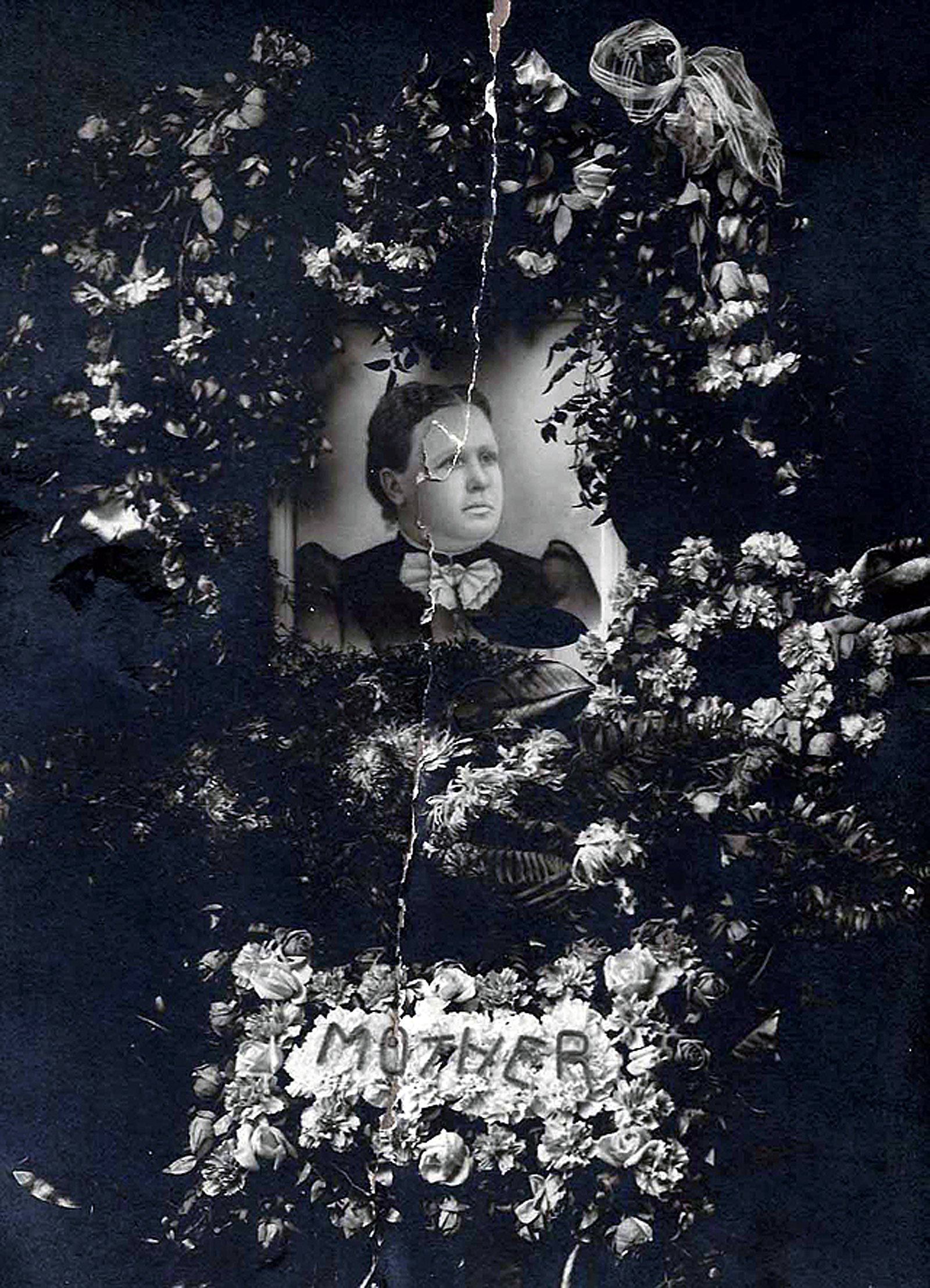

Harriet Brown Funeral

Harriet Brown Funeral

Late the next afternoon, Grandmother's body was brought home in a sleigh from the railroad station, accompanied by Uncle Will and family. I stood holding my Dad's hand as the sleigh was driven up to the house, and the men of the family carried Grandmother's casket into the home she had loved so very much. Family and friends came, and there was much sadness and many tears displayed. Grandmother had been the president of the ward Relief Society for seven or eight years, and had been living in Almy for forty-three years, so she had a lot of friends and had made herself a part of the community.

Dorothy and I, with the rest of the cousins our age who were not old enough to go to the funeral, stayed at the house at the end of lane. We watched the sleighs carrying Grandmother's body, followed by the many families and friends, as they passed on the way to the church. Afterwards we watched them come to the cemetery, which was just down the road a ways from the house we were staying in. An open grave was awaiting the body of Grandma Brown. Nearly thirty-five years had passed since she and Grandfather had buried little Maude Mary. During those years this spot of ground had been watered many times with her tears. Undoubtedly, that day, she had tears of joy as she mingled with her loved ones on the other side. For the living, life would never again be the same without her.

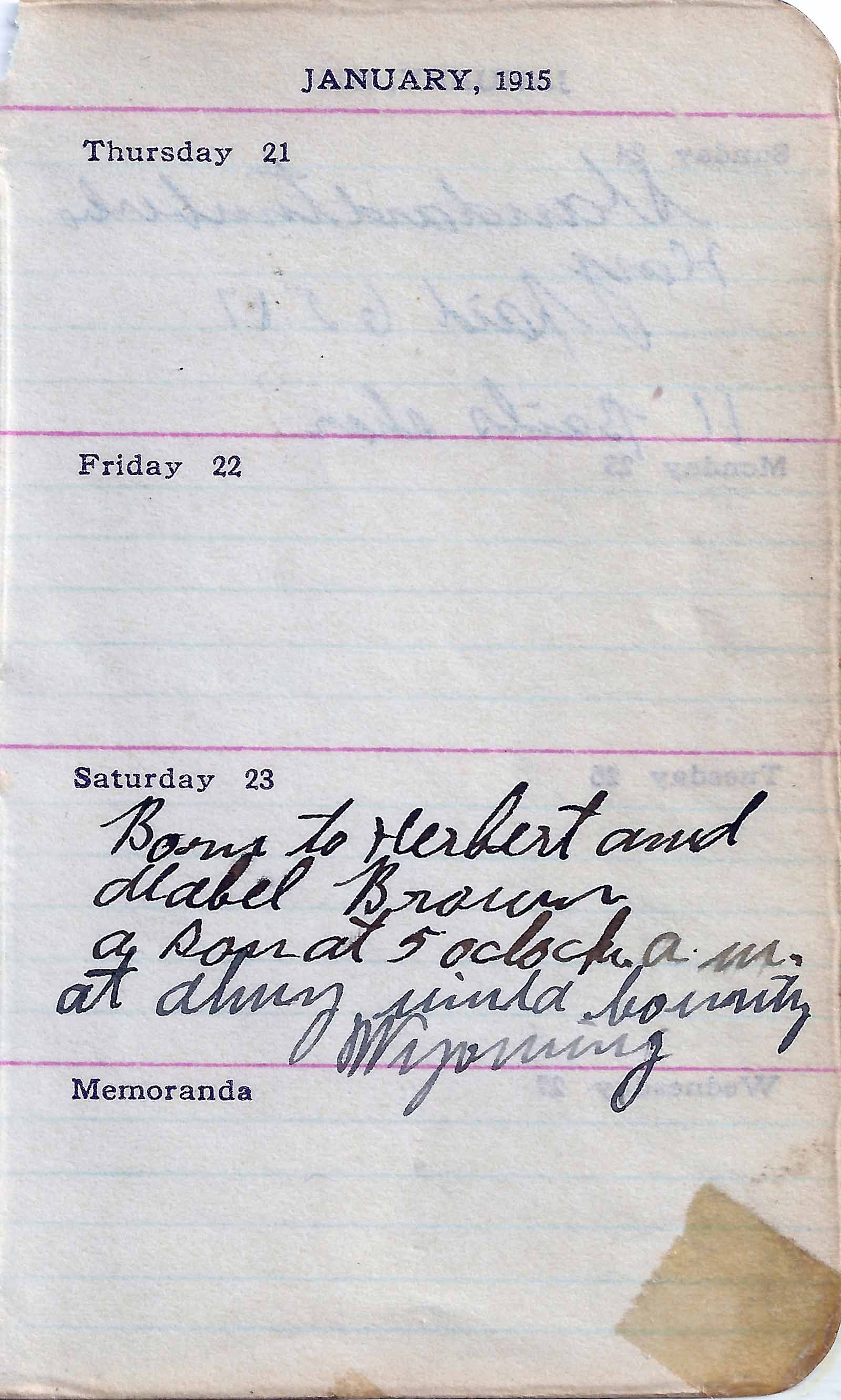

A year after Grandmother's death, Mother and Dad went to Almy for the birth of another child. They took Alice, Violet and me to school in the sleigh, and then went on to Almy. It was the 14th of January 1915. I was six and in the first grade and I remember wanting to go with them and Dorothy. The sleigh box was piled with hay for the horses and Mother and Dorothy were wrapped well in quilts, with the usual hot rock in the gunnysack to help keep them warm.

Several days later, Dad returned and told us we had a baby brother. He had been born in #3 mining camp in Almy, where Uncle Oscar and Aunt Ettie were then living. The baby was named James Herbert, but we always called him Jim.

No story of Dad's life would be complete without telling about Dick. Dick was a horse- a beautiful bay with a star in his forehead and white on some of his feet. He had been born and raised on the ranch and was a very intelligent animal. He had a dual personality. He was very good most times, but other times he would try Dad's patience to the limit. I can see Dick yet, running free, head up, mane and tail flying in the wind. He loved to do that and when in this mood was a beautiful creature.

Dad had taken us to school one spring morning in the sleigh. There had been a lot of snow during the winter, and now as the warm weather commenced, the snow melted and the water gathered in the swales and low places. The ruts in the road had been made hard by winter traffic and were holding the water on each side of the road back, until enough water had accumulated to break through the road. The schoolhouse was not far beyond this particular swale, and we arrived at the school in safety. As Dad drove back over the road, the snow collapsed under Dick, who was on the right side of the road nearest the dammed up water. The snow and water were deep, and Dick was in danger of being drowned. Dad, with the help of the older boys of the school attempted to save the horse. Dick was patient, realizing he was being helped. Some of the boys held his head out of the water, while Dad unhitched Nell, the other horse, and tied her to Dick and pulled him out of the water. If either horse had become upset, the horses, Dad, and some of the boys could have drowned. All I did was watch and cry. Before night the water had broken through and we could get home safely.

Dick could be the most exasperating animal. Dad used to say that if Dick was in the right mood he could pull the load and the other horses, but other times he wouldn't pull Dad's hat off. All of us learned that Dick knew how to work, and that he knew his way home in storms or dark nights. Dick would always get us home. We loved him. Dad would say after Dick had been acting up with one of his bad behaviors, that when the army horse buyers came around he'd sell him. During World War I, the army would come around buying horses. Now, I know Dad would never have sold Dick. He loved him, too. Dick lived longer than Dad.

Making a living was hard work then, with so much of it manual. Dad and our two neighbors, Mr. Lym and Bishop Martin bought a hay baler and would bale hay for others, and sell their surplus hay not needed for their own animals. The baler was powered by two horses walking around in circles. Mr. Martin would feed the baler (put the hay where it could be easily reached) and Mr. Lym would push the hay into the baler. Dad would see to it that the blocks, which divided one bale from another, were placed into the baler, and then he'd tie, weigh and stack them.

One winter, they were working for a man and were living away from home. They didn't return to their families at nights because of the distance. One of Dad's teeth started aching and he'd been nearly crazy for several days and night.

The doctor had told him when he had lost his fingers years before, that the medicine he had given Dad would ruin his teeth and also shorten his life. It was winter and Dad was thirty miles over bad roads from a dentist. At last, after suffering terribly with no sleep, Dad agreed to let Mr. Martin pull his tooth. A piece of wire was tied around the tooth, but as Mr. Martin started to pull the tooth, Dad got up and started to follow him around the table, which stood in the center of the room, with the kerosene lamp on it. They made several trips as Mr. Lym sat watching. Finally, he grabbed Dad and held him, while Mr. Martin kept on going. Dad gave a yell, but he slept that night in peace. I've now had tears come as I write this. Poor, dear Dad!

Not only did they bale the hay, but they would either haul it to Evanston or to the Tie Camp. The Union Pacific Railroad had hired men to go into the mountains, cut down trees and make them into railroad ties, and to float them down the Bear River in the spring high waters. There was quite an operation up in the hills for several years. Houses were built for the loggers and a store for supplies was there. Horses were used, so hay was needed.

Dad and Mr. Martin would load up one day, either on the sleigh or the wagon, and then leave early in the morning. If possible, they would return late in the evening. It was a long hard day for Dad as well as for the horses. It would be dark, especially in the wintertime, before Dad would get home, and we'd all be concerned about him. Chores would be done, and after supper we'd do school work or other things, but always waiting for Dad to come home. Mother or one of us would go outside every once in a while to listen for some sound of a team approaching. In summer, the rattle of the wagon wheels, or the neighbor's dogs barking, as a team went by, alerted us. In winter's cold air, we could hear in the nighttime silence, the sounds of Dad coming home. We'd be so glad to have him home. After he'd eaten supper and had told us all he'd done, and in turn, we had reported our activities, he would maybe pass out a little candy or something he had brought home, and then we would all go to bed. Dad was home and all was well.

There were other things to be done beside baling hay, such as the rooms needing new wall paper. Dad was good at this job and so was Mother. People would sometimes hire Dad to wallpaper their rooms, however, this was one job Dad and Mother could never do together. Many times I've seen Dad finally pick up his hat and go out doors to do something else, while the tension wore off.

Work was essential for their survival, but they also had many enjoyable activities - they, too loved to have a good time. Visits were made among relatives, where family affairs were talked about as they relived the past. Neighbors would drop in for an evening and local events were discussed, and also religion. These were the days long before radio and TV. Newspapers were either weekly or old editions delivered by horseback. Gradually, the mail became better, and telephones were installed by some families. The Church, also, was part of their lives. World problems were followed as much as possible. Sunday School and Sacrament Meetings were held on Sunday afternoons, one following the other. Our sources of transportation were either the buggy or sleigh as weather conditions required. The teams of horses were either tied to the fences or unhitched and tied to the buggy or sleigh. The horses would be tired of standing - cold in winter and hot in summer. This was also true for those of us attending meetings in the church building. Many times in cold weather, the building would get warm by the time we were to go home. Many times we went from a cold building, to a cold sleigh, warmed only by the spirit of the meetings.

The meetinghouse was built in 1908 by the people of the community, to be used as a public meeting place. Most of the people were Latter-Day Saints, but the building was never dedicated. School meetings, ditch meetings, and public meetings of all kinds, socials and dances, as well as church activities were all served by this building. This was a one- room building with a stage at the end opposite the door. There was an organ on the stage, and chairs, and a table served as the podium. A large heating stove was on the main floor at the bottom of the stage. Many a tale this building could have told of the people whose lives revolved around it.

The MIA, then as now, focused on recreation - plays, programs and dances were presented. One play I recall by name only, "Ten Nights in a Bar Room". From all I remember, it was exceptional.

Winter house parties were another source of entertainment. Before the long winters had drawn to a close nearly every home had had its party. Usually, the parties began early and lasted till early in the mornings - dancing, games, songs, and stories. Some of the men would play card games. The women talked, and the young folks usually danced. The furniture was taken from one room to provide for the dances, and then put back before the party was over. At midnight, refreshments were served - always sandwiches - roast beef or some other kind of meat, cakes, cocoa and coffee in the homes of non-members or the not-so-active members. After this break in the activities they began again with more of the same and many times, some of the most active stayed for breakfast of bacon and eggs or what-not. One time I recall, we got home just as it was getting light. Dad and I went and fed the cows and did the morning chores, before we went to bed. Mother and the others had already retired.

Dad loved to fish, and in the summer always had his fishing flies and line in his hat - fishing licenses hadn't come into existence yet. Also, several times we went on fishing trips with neighbors, taking a lunch for the day or staying overnight, sleeping on the ground under the stars and eating the fish and other food as it was cooked over the open fire. Dad would sometimes go by himself for an hour or so of fishing. Seldom did he come home without enough for supper.

World War I changed our little world as the whole world was involved in war. For a while, the United States did not get involved. President Wilson's campaign slogan for his second term was "Peace With Honor - He Kept Us Out of War". Conditions changed and on the 6th of April 1917, war was declared against Germany.

War then, as now, was expensive. Not only in lives, but also in money and food. Every effort was made to obtain them. The government declared meatless, wheatless and sugarless days, substituting beans, rice, honey, cornmeal, fresh vegetables and other foods.

Patriotic rallies were held to inspire people to buy bonds. Patriotic speeches and singing of old and new war songs. Several of the new songs were, "Over There" and "Till We Meet Again" and in school we sang "Canning the Kaiser" to the tune of "Marching Through Georgia". The main slogan of the war was to "Make the World Safe for Democracy."

The hardest part of the war effort was to supply the manpower - young men at first and then the married men were to register for the draft, and many of them were drafted into the service. Dad registered, but we kids were glad he had a bad hand.