Life Story of Adin Ebed Brown by Mabel Brown Blacker

Edited by Ruth Blacker Waite

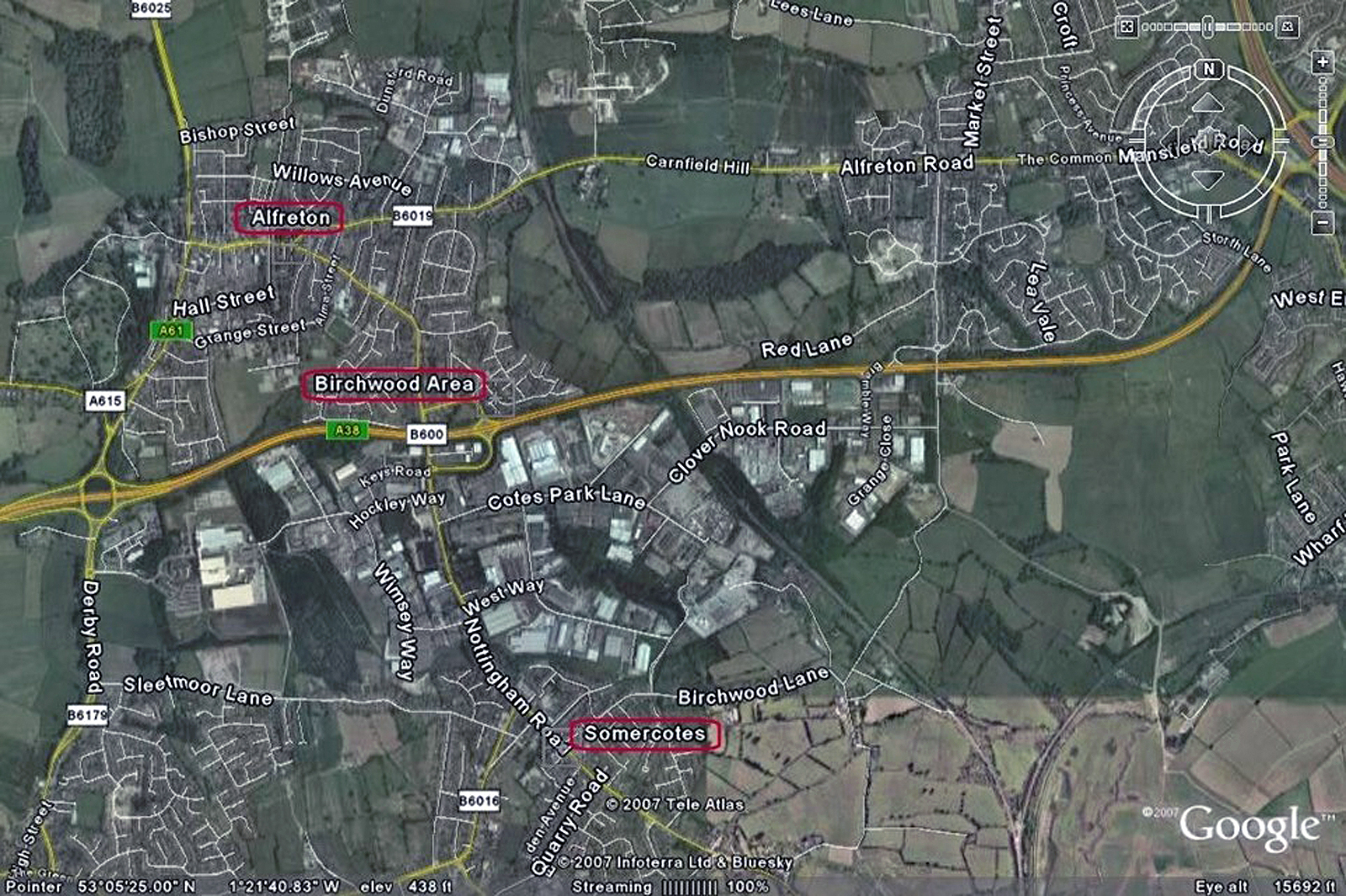

As I sit here, pencil in hand, pensively meditating as to what to write about a grandfather I never knew, only as I have met him in the picture stories told to me by his children and friends, I have before me a few dates and facts concerning his life, but the information is indeed meager. But as I sit, my imagination, unhampered by bounds of time and space, soars from these snowcapped mountains across land and sea to the city of Somercotes, Derbyshire, England. It was here, December 19, 1854, that Adin Ebed Brown, my paternal grandfather, was born. I imagine that his birth brought an extra amount of joy into the home of William and Hannah Clark Brown, because of the death of their daughter, Ann.

Ann was born May 26, 1853 in Alfreton, Derbyshire, England and passed away March 31, 1854 in an area of Alfreton called Birchwood.

It was to this home that the Gospel was carried by missionaries from Zion. Is fervently wish that a record had been kept of the manner in which they heard of, investigated, and finally accepted the Gospel. He, with other brothers and sisters of the family who were old enough, were baptized by Elder Joseph Rawson and confirmed the next day by Elder George Lake. The parents had been baptized twenty days previously. So at the age of sixteen, my grandfather became a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. The spirit of gathering to Zion must have been heard and promptly heeded, for in November 1871 the family left behind kindred and friends and sailed for America on the steamer, Nevada. They were thirteen days on ship. After landing in America, they came west to Utah, staying for a few weeks in Coalville. Then, I presume, because employment could be found in the mines at Almy, Wyoming, the family moved there, and spent the most of their lives there, the father and mother being buried there.

Harriet Hannah Bowers was born Sep. 23, 1855 in Brinsley, Nottingham, England to William and Martha Davis Bower. Her father was a coal miner who had first gone into the coal pits at the young age of seven. He had become interested in the LDS Church when he was seventeen and joined at age nineteen. He worked faithfully as a missionary and held many positions, traveling from branch to branch, walking many, many miles, speaking, passing out tracts, and helping the church grow in that area.

He and Martha were married the 26th of December 1853, and their first child, a little girl they named Penenniah, was born 23rd of September 1854, but sadly died soon after and was buried on the 11th of October, the same year, being just a little over two weeks of age.

Their second child, was our Harriet Hannah. Ten children in total were born to the couple in England with six passing away at very young ages due to various diseases. These were Penenniah, William, Leonard, Christopher, Lucy and Elizabeth. After coming to America, William and Martha had five more children, Rose Ellen, John, Samuel, Martha Elizabeth and Heber Henry. Rose Ellen, Samuel and Heber Henry died as infants.

We know little of her younger years, though her father, William, recorded many of the family's important information in a diary he kept. We do know that Harriett was baptized into the LDS Church at the age of nine or ten, December 31, 1864. William said that because of the persecution of this religion in England at that time, the baptism was held at midnight in order to escape the trouble that would be caused by non believers.

At the age of fourteen, Harriett was put into "service" as a hired servant. He recorded that on June 26th 1869, Harriet entered into service in Nottingham for 1 shilling 6 pence for the first month. Then July 24, 1869, he went to see her and to arrange for her wages at 2 shillings per week. Usually, as children went to work, most of their wages went to help the family. Then on Oct 25, 1871 she went to work for Mr. J.S. Smith, Esquire, in Chesterfield at 1 pound 2 shillings per week.

The area in Derbyshire, England where Adin was born. Brinsley, Harriet's birthplace

is about 4 miles southeast of Somercotes.

The area in Derbyshire, England where Adin was born. Brinsley, Harriet's birthplace

is about 4 miles southeast of Somercotes.

The decision was made to leave England behind, partly because the economy of coal mining was bad. Many mines were closing because the veins of coal were running out. It must have been hard to leave other family members and those six little graves behind, but the rest of the family immigrated to the US , leaving Liverpool, England June 12, 1872 on the steamship Manhattan and arriving at Castle Gardens, New York June 26. On the ship was a group of LDS members traveling together. William's and Martha's living children were Harriet, age 16, Alvin 11, George 4, and another William listed on the ship's manifest as an infant. They stayed the night there, and next day at 1:00 they crossed the Hudson into New Jersey and got in a railroad car for the trip west. They arrived in Almy, Wyoming July 4, 1872 where there was work for William in the coal mines. They probably moved into a company house, and joined with other members of the LDS church and began life in America.

We don't know the details of how Harriet Bower and Adin Ebed Brown met in Almy. It is possible the families knew each other in England as they were from the same areas.

Aden Ebed and Harriet were married Sunday, September 28, 1873, at Almy, by Elder Samuel Pike. During the next nineteen years, they had ten children born to them six sons and four daughters, namely, Martha, William, Herbert, Ann, Maud, Adin Ebed, Jr., Frank, Charles, Harriet, and Lyman.

Because of Harriet's experience working in homes of well-off people in England, she knew how to manage a beautiful home, and was able to fill it with beautiful things. A relative reprted, "Cleanlyness and things in order was the way she lived and a perfect seamtress."

Her sugar bowl and butter dish

Her sugar bowl and butter dish

In 1899, she and a friend, Mary Morris from Evanston, decided to take a trip back to England to visit family and friends. They had a wonderful time, and Harriet purchased a beautifully carved rocking chair to take back to her home.

On August 26th 1899 the two friends boarded the ship, City of Rome, and sailed from Glasgow, Scotland with 1,300 people on board. The trip was uneventful until on August 31, 1899, the ship entered a very cold, extremely foggy area just off the coast of Newfoundland. Lookouts were doubled to watch for icebergs. Just before 6:00 that evening, the ship was hit by a berg with a loud crunching sound. The ship actually slid up onto a part of the berg, throwing people to the floor. Of course, panic ensued and for a time the captain told the passengers they could either get into lifeboats, but with the extreme cold, they would surely perish, or they would have to go down with the ship. Harriet and Mary went to their cabin and locked themselves in, rather than face the prospect of getting into the icy water. They prayed for protection and worried about their families at home.

Also on the ship was a group of LDS missionaries returning home. One, who had served in Scotland, called for all Church members along with anyone else who wanted, to listen. He told them the ship was on an iceberg, and that the captain was making emergency preparations. He told his listeners not to worry as they "were in the hands of the Lord." Soon with a great noise and shaking, the captain was able to back down from the iceberg. After an examination, it was discovered that though the ship was damaged, it was still seaworthy, and able to continue on its way to New York. Later, Harriet and Mary found out that the missionary was David O. McKay, who would later become an Apostle and the president of the entire Church.

The City of Rome

The City of Rome

Read the newspaper article in the New York Times here.

New York Times, 26 August 1898

The City of Rome in Collision with an Iceberg

It is only by the grace of God that we are here, safe and well, after having been exposed to one of the greatest dangers of the sea--a collision with an iceberg."

This was the opinion of the 1300 men and women who arrived on the Anchor line steamer City of Rome from Glasgow yesterday. Off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, 1,000 miles from New York, the great ocean liner ran into a great berg, stuck to it for a few seconds, and then tacked off. The shock of the collision threw persons on deck from their feet and caused intense excitement on board.

In ten minutes all the flurry was over, but in that short space of time many of the passengers were frightened badly. Some fell to their knees and prayed, others sought life preservers. But through it a11 the officers and crew acted gallantly, and finally succeeded in calming the fears of the frightened ones.

TWO PASSENGERS MADE INSANE. Two passengers, who had been i11, were temporarily insane. After the few minutes' experience with the big berg, the City of Rome steamed on her way and arrived in port yesterday, little the worse for her encounter.

The City of Rome, commanded by Captain High Young, sailed from Glasgow on August 26, with an unusually heavy passenger list, Besides the crew of 297 men, there were 450 first cabin, 230 second cabin and 322 steerage passengers. The saloon passengers were for the main part persons returning from summer vacations abroad---among them a score of Scotch Presbyterian ministers on the way to the Religious Congress in Boston.

The voyage was uneventful until the afternoon of Thursday, August 31. The weather was exceeding chilly, and a dense fog hung over the sea. For this reason most of the passengers were in the saloons below deck. Captain Young remained on the bridge, without even going below for his meals.

On Thursday afternoon, the fog became denser than ever. The chill of the atmosphere increased to biting cold, and this, together with floating particles of ice in the water, told that an iceberg was near. On this account the City of Rome's engines were reduced to a nine-knot speed, and the vigilance of the lookouts was increased.

A TREMENDOUS SHOCK. At ten minutes before 6, while those who dined at the first table were seated at dinner, a crunching noise was heard. Next, a tremendous shock was felt, and the big ship staggered for an instant, trembling from stem to stern, The waiters in the dining halls were thrown from their feet and went crashing to the floor. All thought that the ship had struck another vessel, and the first impulse was to rush out on deck.

In cabins and staterooms, some men and women fell to their knees and prayed, others rushed for life preservers, and one passenger, who had become mentally unbalanced through illness, became violent through the excitement. He got a knife and flourished it above his head, threatening to kill himself and others. He was overpowered and kept under guard for the rest of the voyage.

The Rev. Father L. Dubois of Sa1t Lake City, Utah, was among the passengers. He was in the cabin at the time of the collision. "There was considerable excitement,"he said, "and I think it must have been worse below than it was on deck, Those who were in their staterooms ran out to the cabin and on deck, their faces blanched with fear. Many dropped to their knees and prayed, while others swore."

But even in such times of supposed peril something ludicrous happens. Many of the passengers rushed for life preservers, and the most had them on any way but the right way. One man ran out on deck, carrying a heavy valise in each hand, as though he thought he would be allowed to take his baggage with him it if was found necessary to take to the boats.

SONGS BY PUGlLIST'S PARTY. Frank Craig, the negro pugilist, known as "The Harlem Coffee Cooler," was among the passengers, with his wife and child, as were the members of a theatrical company which he heads. He was on deck at the time of the collision, and the first thing he did was to run below to their state room to look after his wife and child. When he was told that there was no danger, he and the members of his company sang "coon" songs and did several "buck dances"to calm the passengers.

CITY OF ROME, FEELING HER WAY IN THE MIST, CLIM8ED UP AN ICY LEDGE, POKED HER NOSE BETWEEN TWO PEAKS AND SLIPPED OFF IN SAFETY. PASSENGERS FRIGHTENED BUT NOT HARMED.

The figurehead of the gigantic single-screw Anchor liner City of Rome, representing a Roman gladiator, exhibited a crushed forearm when the vessel reached New York yesterday, and the short dagger which the right hand had held was missing. The left hand, which had grasped a shield, was amputated at the wrist. The mutilated figure was the sole evidence above the water line of a collision between the City of Rome and a big iceberg off Cape Race last Thursday and the peril to which the nearly 1,300 persons on board had been exposed.

The prudence and skill of Captain High Young, the steamship's commander, in stopping the engines at the first sight of ice saved the liner from quick destruction and her passengers and crew from death.

The City of Rome left Glasgow on August 26 with 671 passengers in the saloon and second cabin and 322 in the steerage. Her crew numbers 300, so there were 1,293 persons on board. She made the usual stop at Movi1le and then steamed on into the Atlantic to face a high westerly wind and sea. This the big vessel buffeted until August 31, and at 3 o'c1ock that afternoon she entered a fog belt that closed around her to thickly that double lookouts were posted on the forecastle head and another in the crow's nest on the foremast.

CLOSE WATCH FOR ICE. Speed was reduced to eight knots, and the lookouts were warned to watch for signs of ice. Captain Young himself took charge on the bridge with Chief Officer Blakie and Third Officer Doctor beside him, and the liner crept for nearly three hours through the ever thickening mist.

As 6 o'c1ock drew near, the saloon was illuminated and the long rows of tables rapidly filled with passengers for their dinner.

Suddenly the air grew cold, and Captain Young knew he was near ice. A second later he sighted a hummock twenty feet high and twice as long off the port bow. The signal to stop rang in the engine room and the helm swung to port, The liner veered to starboard and the ice hummock floated past on the port hand.

It had hardly reached the stern when the form of a berg 175 to 200 feet long and fully forty feet high loomed up directly in the steamship's course. The lookouts and the officers on the bridge saw it at the same moment, and the signal, "Reverse full speed astern," was followed by the churning of the big screw as it strove with a11 its power to avert the collision.

HER BOWS ROSE IN THE AIR. But the vessel's headway was too great to prevent an impact. Her bows suddenly appeared to rear in the air as she struck the ledge of ice that projected under the surface from the base of the berg, and then a series of mighty vibrations shook the vessel as she crunched her way up the slippery incline until her bowsprit poked over the top of the berg between two peaks, one of which towered twenty feet above the Rome's bows. She had struck the berg fairly in the center.

At the first crash the tables in the cabins were emptied of dishes and food, while broken crockery and glass were hurled through the air and the diners were sent sprawling among the debris The vessel rang with the screams of women and children who were sure the City of Rome was sinking. In a moment there was a rush for the main companion way as the passengers surged toward the promenade deck. But there were met by officers who calmed their fears. The truth was told at once and the voyagers were assured that no harm had been done.

The big engines did their work and the steamship slowly backed away from the berg for fifteen feet and then the great ice ledge under her bow snapped off and the City of Rome floated, with a thousand tons of ice under her starboard bilges, which gave her a list of fifteen degrees to port.

CAPTAIN SAW NO OTHER ICE. "It could not have been helped," said Captain Young yesterday. "We had stopped the engines the moment I saw the first bit of ice and that hummock was the first, and the iceberg the last we saw. The berg was in latitude 48.30 and longitude 48.44. "When the steamship slipped off the ice we steamed slowly ahead for two hours to get away from the neighborhood of the berg. It disappeared a moment after we left. When we had put sixteen miles between us and that berg the vessel was hove to until it fully cleared, at 12:30 o'clock Friday morning. Then full speed was resumed.

"I do not think the fore peak plates below the water are damaged, but a diver will take a look at them. All of our compartments, even No. 1, which is directly ahaft the fore peak, are tight. We have not taken in a drop of water as a result of that bump,"

The voyagers expressed their appreciation of the skill and care of Captain Young in a set of resolutions adopted on Friday.

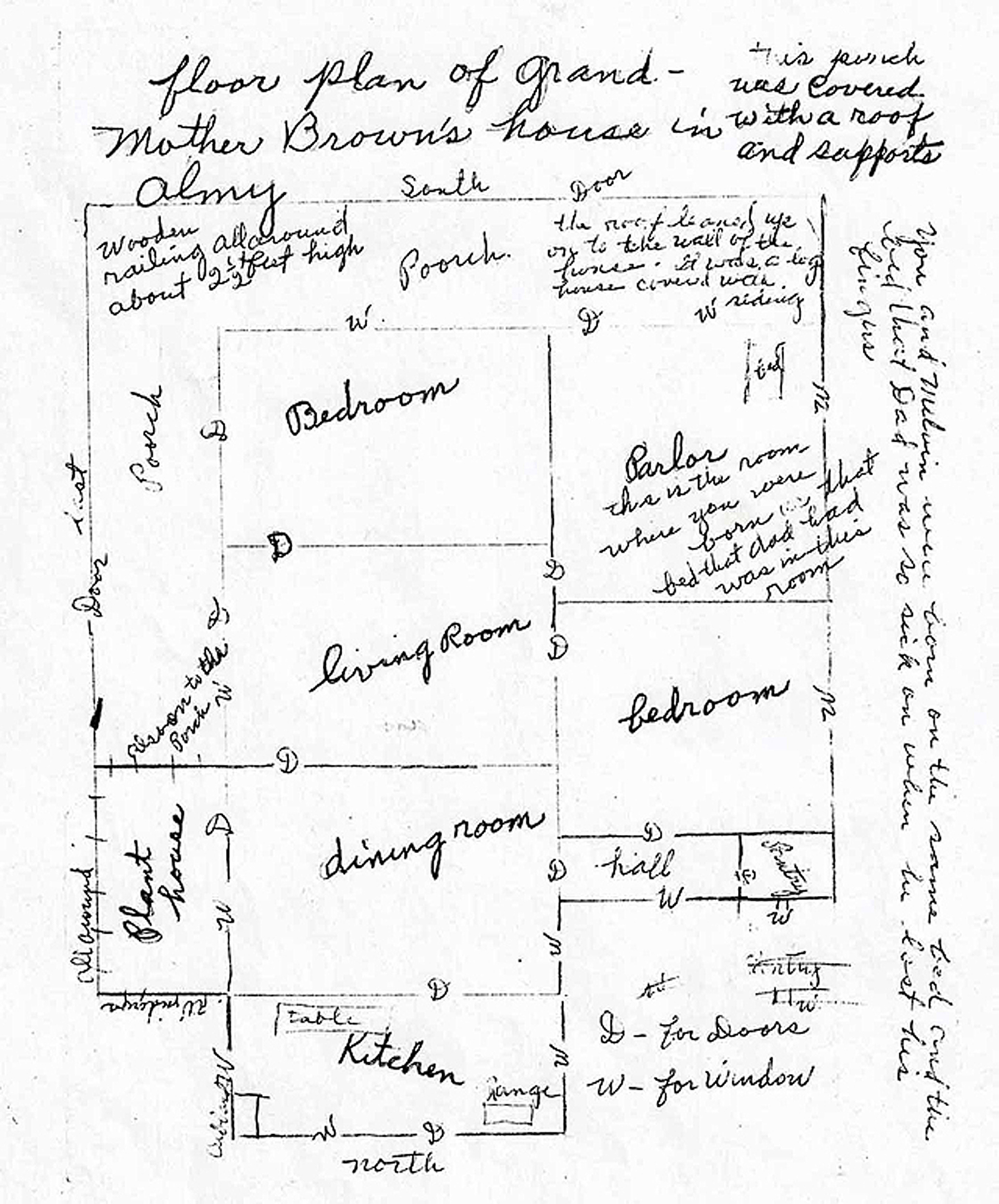

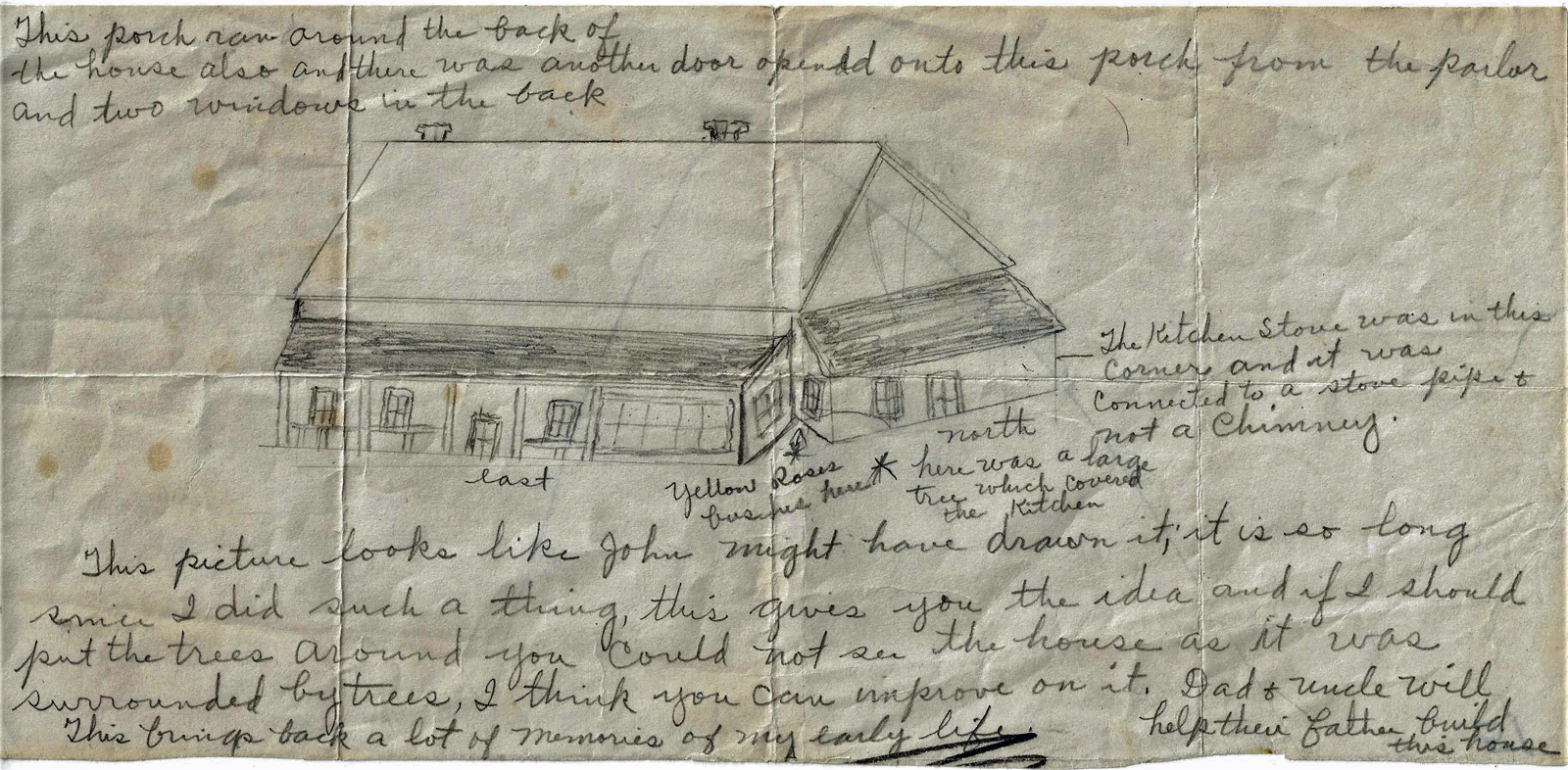

Looking through a record book wherein he kept the vital statistics of his family, I found this entry: "This is to certify that I, Adin Ebed Brown, this 15th day of February, 1876, filed on one quarter section of land". It was on this land that he proceeded to make his home and through the industry and resourcefulness of he and his wife, they made it a very attractive and comfortable home. I have heard that it was one of the most beautiful homes in Almy. As a little girl I remember admiring the lawn, shade trees, and flowers, as well as the garden. There are several things that appealed to my childish eyes. The one in particular was the chandelier that hung in the living room. It I thought it the most beautiful thing as it glittered int he light, reflecting as many colors as the rainbow, and the other was the big heating stove through which the fire could be seen through the front.

The floor plan of Adin's and Harriet's home in Almy

The floor plan of Adin's and Harriet's home in Almy

A drawing of their home

A drawing of their home

In September, 1878, they went to Salt Lake City, and on the 26th in the Endowment House, were sealed for time and eternity.

He was called to be Superintendent of the Almy Sunday School and was set apart June 18, 1882, with Edward Burton and Joseph B. Martin as counselors. This position he held for eighteen years. He loved children and had an influence for good upon their lives. I've been told that at celebrations such as 4th and 24th of July, that he could be seen beating a pan, and followed by all the children at the celebration.

All of his children tell of his observance of the principles of the Gospel, and of the high standards he desired that they should keep. It is said that he never allowed anyone, not even strangers, to smoke in his home. He loved his family.

He worked for many years as clerk in Blyth and Fargo store in Almy and recently I heard of the manager of the same company praise his honesty and integrity.

Harriet and Adin with children.

Harriet and Adin with children.

I have no record of dates, but he also homesteaded 160 acres of land at Hilliard, and helped in making a ditch from Bear River in order that water could be obtained for the land. This was the second ditch in that community and now its the largest and the company is now known as the Bear River Canal Company.

In 1900 he fell into a hole at Spring Valley, Wyoming, and was in it for about seven hours, being unconscious when he was found. As a result of this injury, his heart was permanently dislocated and he was never really well again. This accident was the cause of his death four years later.

He was set apart as counselor to William Beveridge of the Almy Bishopric, May 25, 1902, under the hands of Charles Kinopton, of the Woodruff Stake Presidency.

He died June 30, 1904, at his residence in Almy, Wyoming, and was buried July 3, 1904, in the Almy Cemetery.

His death is covered in more detail in the history of his son Herbert, called "Within the Walls of Home".

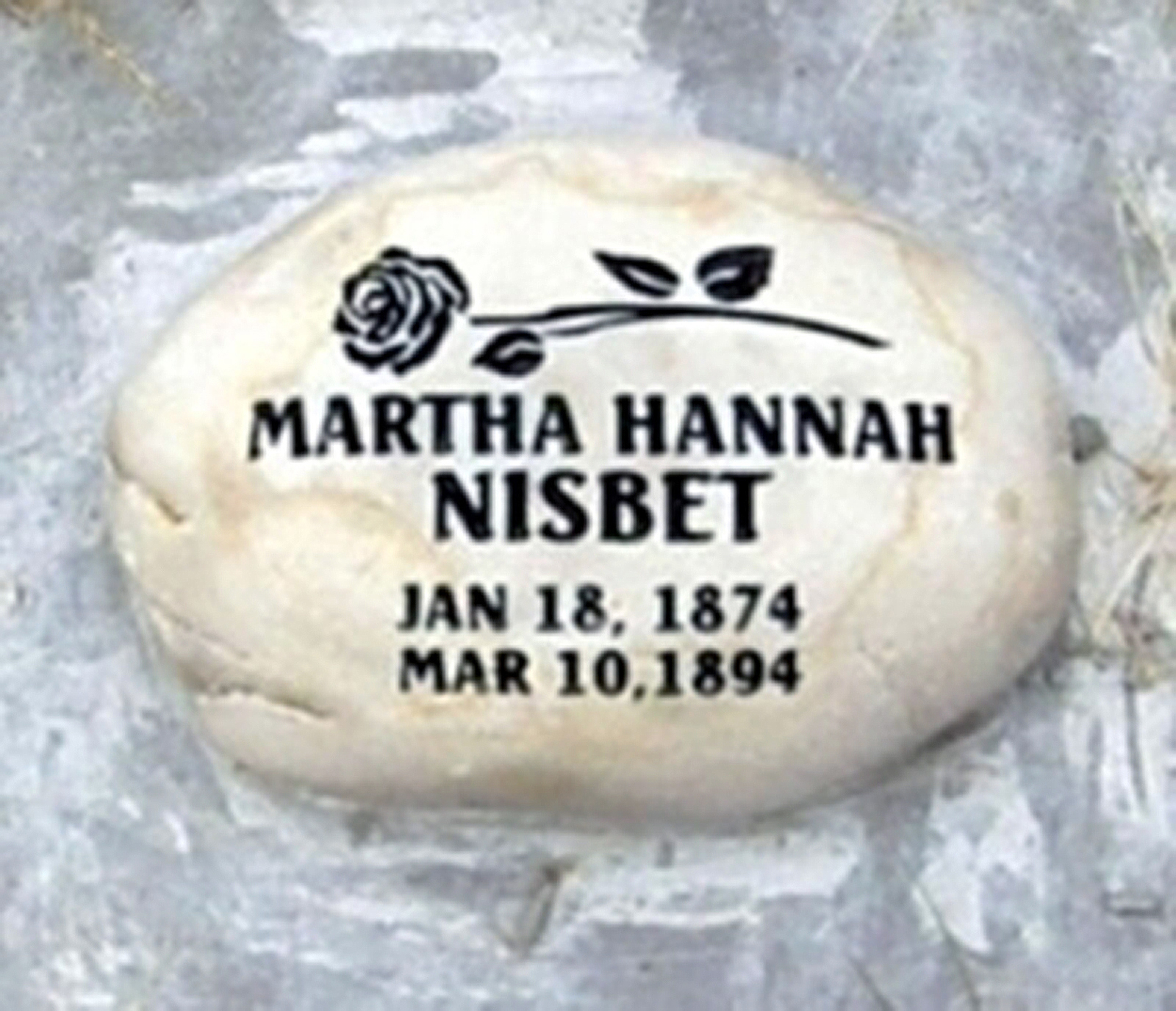

Much information concerning my mother's history of Adin Ebed and Hannah Hariet Bower Brown, is included in her history of their son,and her father, Herbert Brown, entitled Within the Walls of Home. However, at the risk of duplication, I feel some of this information should be repeated, in order to round out this very short history. At this point, while talking about their children, it should be stated that they lost some of them through death. Their fifth child, Maud Mary, died August 21, 1881, when she was about six weeks old, and was buried not far from their first home, which I understand was built near the road. Hers was the first grave in what is now the Almy Cemetery. Not long after, her grandmother, Hannah Clark Brown was laid to rest near her. Adin's and Hannah's oldest child, Martha, married William Nisbett but sadly died March 10, 1894, just after the birth of their first baby, Harriet Isabella. About two months later on April 7, 1894, the baby also died. William Nisbet married another young woman, who also died at the birth of their first baby, and they are buried next to Martha.

Adin Ebed Jr., suffered from a serious heart condition all of his life. One night, when about seventeen years of age, he was staying the night with his friend, a Titmus boy in the loft of the Titmus barn. The other boy was asleep, but Adin had been reading by the light of a lantern. When he reached to turn the lantern off, he saw a well-dressed man climb up the ladder from the floor below, who was also reaching for the light. In his fear, Adin remembered the counsel of his mother, and rebuked the personage in the name of Jesus Christ, and commanded him to depart, which he did. He told this account to his parents, and some time after on July 7, 1900, he died from what the family considered a shock to his heart. He was buried with his sisters, niece and grandmother in the family plot.

When coalmine # 5 exploded, killing many of the miners, one of the dead was Adin Ebed's brother, Willard, who left behind a wife and seven young children. Many of the deceased were buried in the cemetery, which started as a place for the family to lay their loved ones to rest, but soon became a community cemetery.

His brother, Frank, died from a disease, as a young married man, 22 years of age, on February 16, 1906, and was also laid to rest in the family cemetery.

Ruth Blacker Waite