What an interesting story it would have been had we been able to have included a relatively detailed account of the long, but undoubtedly interesting, journey from mid-eastern Illinois to the west across Iowa, Nebraska, and all of Wyoming excepting five miles from its western border connecting Utah! So far as we are aware, not a single person of the three generations involved, grandparents, parents, nor children left a word in writing of this experience, nor are there amongst us, their descendants, anyone who recalls anything that any of them related specifically about the journey.

Their story could have told us the number of days and nights spent on the swinging and swaying cars, connected with the constant rumbling of the iron wheels as they contacted the hard iron track, just under the floor of the coach they were walking on, or supporting the chairs they were sitting and sleeping on. By this early period of railway history, George Pullman probably did not have too many of his but lately designed and famous Pullman cars on the road. Even if those modern sleeping cars were on this train, it is most likely these traveling families would not have been able to have afforded them. Certainly Pullman's dining cars had not yet been designed, so their eating would have had to have been from previously prepared lunches or, perhaps, some food-stuffs which they might have been able to purchase at various stopping places while the locomotive was taking on water and/or coal for another leg of its journey.

Undoubtedly the older children, Uncle George, then ten, Aunt Sarah Ann, a little over eight years of age and Aunt Mary, five years old, would have found this a joy-ride - part of the time - but Tom, just three and baby Maria were yet at an age where extra entertainment may have been required.

Considering the early years of the railway system, could one 'guesstomate' three days may have been pretty well used up - probably two nights - before Evanston was reached? A written account at the time may have reduced the three days to two, but be that as it may, the party undoubtedly reached their destination. After they reached Evanston there was yet another approximately five miles in team and wagon to reach their to-be homes in Almy. What previous arrangements they may have made to have someone meet them or to have arranged for their homes or, perhaps, a place to stay until they could make arrangements for a home we do not know. It seems we shall continue to wonder about these matters until we join them over yonder.

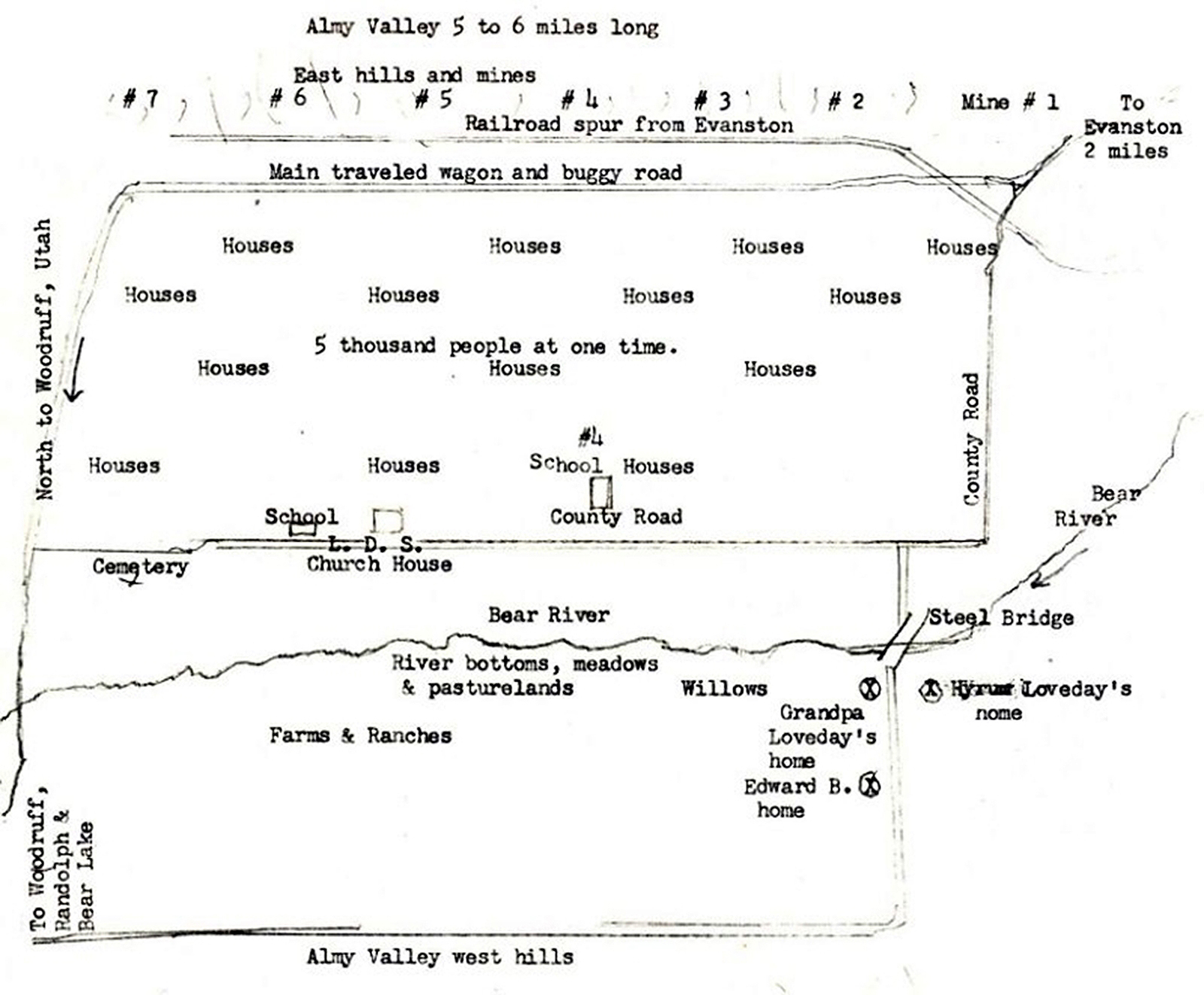

Coal had been discovered in Almy about 1867 or 1868, this prior to when the railroad had become transcontinental after which the demand for coal increased. Not only was there need for the locomotives but also the growing industry and the heating of homes required coal to be shipped. Almy became a busy, small metropolis. About two miles to the north of Evanston, a vein of coal was discovered which became known as Mine #1 and eventually seven mines were dug into the little valley's eastern hills, covering a distance of five or six miles. Not all were put into operation at once, but as the first ran out of coal, the system was extended and a new mine was dug. A spur of the railroad was extended from Evanston to the mines and parallel to the spur was a road for wagon and buggy traffic. Facing the road, houses were constructed as homes for the miners and their families and behind them streets or access roads were extended toward the west and bottom of the valley until literally hundreds of houses were eventually built and occupied. The little valley was - and remains - approximately two miles wide with Bear River running to the north away from Evanston, about a mile from the mouths of the mines. At one time, practically the entire area between the river and the eastern hillside of the valley was covered with homes and extended north and south perhaps five miles, enough to house approximately five thousand people.

Now, back to the newly arrived immigrants: Unquestionably the real reason for their migration was to find a way to sustain and provide for themselves and families, particularly so the Edward Blacker family whose numbers were increasing and whose needs were multiplying. There was coal mining to be done here in Almy, and Edward knew little other than coalmining. But the Lovedays: Grandpa Loveday was a farmer by trade and at heart, but his previous farming experience seems to have always been for the other fellow - he had been but an agricultural laborer. Surely, Almy was not the best place in the world for a to-be farmer. The 7,000 feet elevation and the rocky soil was not overly conducive to farming - more for ranching. Grandpa Loveday ended up on what is known as meadowland which calls for many acres for any great production. Too, Isaac was over sixty years of age - not an ideal age for heavy work with the soil. His family had grown up and had left home excepting for his youngest living son who was 21 or 22 years of age. We can contribute the Loveday's reason for coming to Almy was to be near his family, particularly his daughter, Althera and this proved to have been the wise thing as we shall see later.

The coal companies, as was customary even in England, provided housing for the majority of their employees. The houses were known as 'company' houses which were leased to the workers and the rental was deducted from their pay-checks. Also, the company often had grocery businesses and offered credit to the miners and their families to be paid for at the end of the months, also from their checks.

The county provided the schools which naturally were paid for by the workers by way of taxes. Various churches provided facilities for their memberships with expenses and upkeep paid by voluntary contributions. It so happened there was a strong Mormon element amongst the families of the community and the Almy ward at one time became the largest ward in the entire surrounding area. As early as the 1870s the members of the Mormon Church met in the so-called Old Almy Camp at Mine #1 a couple miles north of Evanston and by common consent, appointed John Jolley, one of their members to preside.

With the railroad reaching transcontinental status in 1869 at Promontory Point at the north end of Great Salt Lake, the possibilities for shipping coal greatly increased, which in turn, brought a great influx for needed miners, and the population at Almy almost overextended itself. Before 1870 had come to a close, the Mormon Church advised President Budge, president of the Bear Lake Stake with headquarters at Paris, Idaho, to include this Western Wyoming area in his stake and officially organize a branch at Almy, which was done. Woodruff and Randolph, Utah, were already new wards in the Bear Lake Stake which, itself was also relatively new.

At about this time, the Almy branch built a new branch chapel down on the County Road about a mile across the new housing addition directly west of Mine #5. The distance of approximately 70 miles over dirt roads with a difficult canyon road into Laketown on the south end of the Bear Lake, prompted a transfer of the western Wyoming branches of Almy, Evanston and Rock Springs to the Summit Stake with headquarters in Coalville, Utah, a close distance by approximately 40 miles. In 1877, Almy was made a ward with Bishop James Bowns as its first bishop and he was serving in that capacity when the Loveday and Blacker families moved to Almy.

Again, returning to our families, there is little to report excepting eventually, they became settled in their respective houses. How it was done we don't know, but three houses became available in a single neighborhood. As one follows the sketch of the area shown above, leaving Evanston, the road to Almy is picked up in the bottom right hand corner which first leads to Mine #1. Leaving the main road and turning to the west on the County Road for approximately one mile, the road makes a right hand turn toward the north. After approximately 1/4 of a miles, another road turns to the west and within another 1/4 mile one comes to a steel bridge crossing Bear River. Within one or two hundred yards of the bridge was the house the Lovedays moved into. Another hundred yards or so on the same side of the street became the home of the Edward Blacker family and back near the bridge, but on the south side of the road, was a home Uncle Hyrum Loveday and family moved into.

These houses were not company houses but privately owned. By the time of the 1900 census and the Lovedays still being there, the record reveals the Grandpa Loveday owned the home. The Blacker family did not remain in Almy that long, but we find no evidence in the county records of Edward owning property during the 1880s and 1890s. If we are not mistaken, Uncle Hyrum Loveday eventually ended up in the Montpelier area, with no record of his having owned the house in Almy.

So, before fall definitely, and probably as early as spring of 1884, these families became settled in Almy. Grandpa Edward and, undoubtedly, son George, found employment in the mines and apparently started working soon after their arrival.

Perhaps, before another subject of the family is entered into, the location of these new homes was originally pointed out to us by those who were there. Commencing in the fall of the school year 1937-1938, the writer started teaching in the Almy School where I taught for three years. Two of our children were born in the little teacherage which was located on the school grounds. On a visit by my parents, Thomas and Hettie, my father had me drive to the spot where their home once was. He was but four when they moved to Almy and the family left when he was 16, so there was no question in his mind, for the steel bridge - which when he was a boy seemed so large, was surprisingly smaller when he made the visit with us. The entire Almy area which was thickly housed when he was growing up had completely reverted to rural ranchland with very little evidence of their having been a town of a few thousand residents. The family houses just west of the river bridge had either been moved off or torn down, for by the time of our visit it was all in pasture land with no evidence, excepting clearings, where the houses once stood.

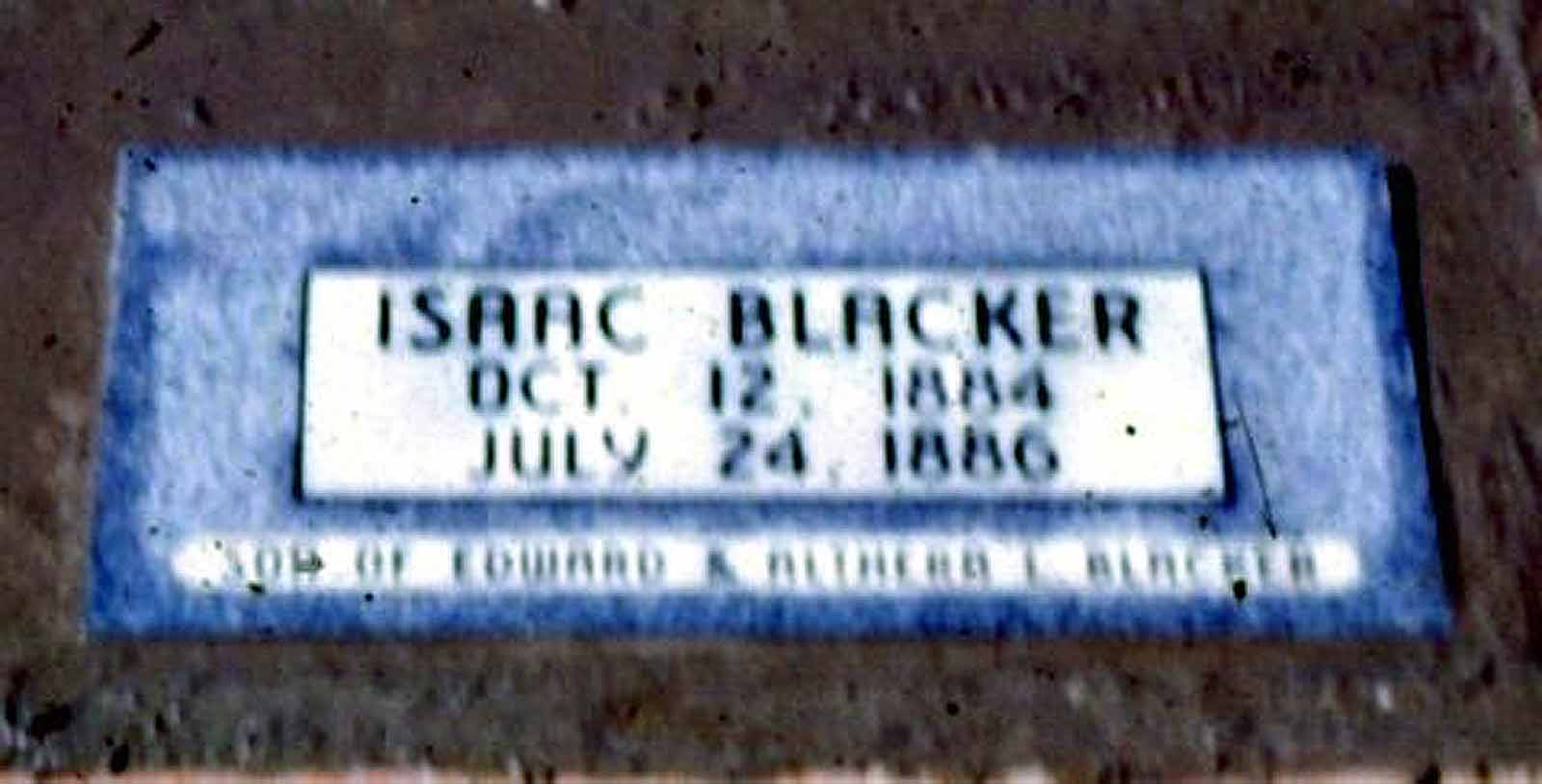

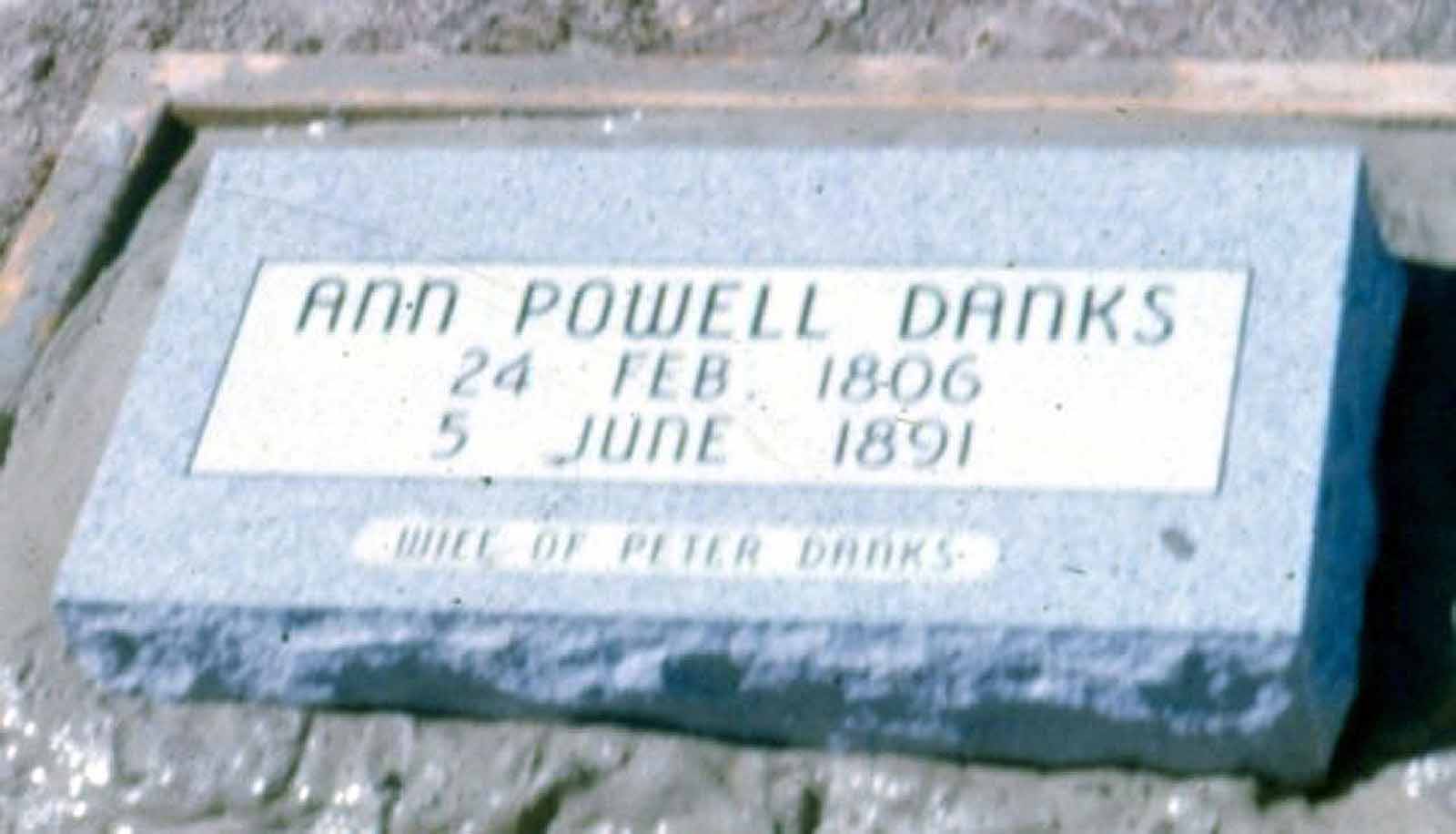

At one of the Edward Blacker Family Organization reunions held in September of 1966 in Evanston, two grave stones were placed in cement in the Almy cemetery. One was for baby Isaac, born to Edward and Althera Blacker on 12 October 1884 and who died on the 24th of July 1886. The other was for my 2nd great grandmother, Ann Powell Danks, born 24 February 1806 and who died on 5 June 1891 in Almy. She was the mother of Great-Grandmother Mary Danks Loveday - Isaac's wife, and wife of Peter Danks of our direct pedigree line. She had had a wooden marker at the head of her grave which had rotted off and fallen over, and after completing this work the family caravan drove up the County Road to the steel bridge which we crossed and parked on the road in front of where the homes of the Lovedays and the Blackers once stood. Uncle Will Blacker, who was with the group, pointed out the respective places where the houses once stood, and confirmed what his brother Thomas had pointed out nearly thirty years before. Uncle Will was born in Almy and lived in the house of his parents until they moved to Star Valley, arriving in Afton on Uncle Will's tenth birthday.

The amount of land connected with each of the homes is not known. Undoubtedly they were small acreages, but it seems questionable that any one of them would be at all sizable such as a meadow where hay stacks would become part of the operation. The Blackers had a team of horses, for Uncle Will often mentioned that as he was growing up as a young boy, he would drive the laboring portion of the family to work in a wagon or buckboard, and return home to go to school on foot. This was the impression that was was left.

It may not be unthinkable that the Blacker family may have had a cow to assist with the feeding of their growing family and that there was pasture enough for the horses and a cow, if they had one, for summer feed. Our father, Thomas, on occasion, referred to the fact that one of his boyhood chores was to cut willows and stack them for drying to be used for future kindling and quick fires. While we don't remember him saying as much, it would seem, with such a task as this, that it would be likely that he would go further afield than their own property and, perhaps, go at random along the river banks even were it was the pasture-lands of nearby neighbors. Dead and dry willows would certainly make far better kindling wood than green willows, even if they were allowed to dry for a season.

With the short seasons for growing gardens, a good garden would have become a challenge. Undoubtedly it would have been Grandpa Loveday who would have supervised the raising of gardens not only on his plot, but undoubtedly, would have given counsel with the Blacker garden. Only the hardy vegetables would have been profitable in Almy such as carrots, beets, onions, cabbage and other such mainstays in any garden and perhaps a few potatoes. The soil was rocky even along the river bottoms, but less rocky than the higher ground.

We are not sure but that Grandpa Loveday may have had short stints with work in the mines. While his nature and life style was not geared to mining, it would seem probably that a little of it may have been done to supplement family income. There undoubtedly, were a few farms and ranches left separate from the houses, on which, perhaps farm help was needed. There are a number of possibilities he could have turned to without going down into the mines. Some of these undoubtedly were resorted to.

We are aware that good health was a scarcity in the Loveday household. Particularly with Grandma Loveday. Due to her poor health, granddaughter, Mary Blacker, third child of Edward and Althera Blacker, became a permanent member of the Loveday household since her early childhood. In referring to Aunt Mary, Uncle Will said of her, his sister, "Grandma Loveday took her (Aunt Mary Blacker Wilkes) when she was a little girl and Grandma Loveday kept her most of the time. I always thought that Mary was Grandma Loveday's girl. Grandma raised her. Mother always used to tell us to never let such a thing happen in our families - that is, never let some one else raise one of our children". (A direct quote from a taped interview with Uncle Will on the 27th of July 1965. This interview is so pertinent to the subject at hand that parts will be copied here verbatim. Designating who is speaking the initials UW: will indicate Uncle Will Blacker. The initial 'L' will indicate the questioner, in this case, Loyn.)

L: Uncle Will, you were born in 1886 and your folk were in Almy?

UW: Yes, and I was the seventh child.

L: The seventh child in the family and four of them, Uncle George, Aunt Mary, Aunt Sarah Ann and Dad (Thomas) were born in the old country and Aunt Maria in Illinois before they reached Almy. If I understand correctly Grandpa Blacker came to this country first, is this correct?

UW: Grandpa Blacker and Grandpa Loveday came over first (Uncle Will was referring to his own father here and his Grandfather Loveday - his mother's father.) and left the women and children in the old country.

L: Where did they come to and how long were they here before having their families follow?

UW: I don't know that. They came to go to Pennsylvania. I don't know whether Dad's sister was in Pennsylvania or not. (He is referring to his Aunt Fannie who married Thomas Lewis in Wales and who came to this country. This was mentioned earlier in the story. L.B.) They went to Pennsylvania because there were coal fields there and they had been coal miners in the old country.

L: Did Grandpa Blacker and Grandpa Loveday go back to help their families come over?

UW: No. Grandma Loveday - I don't know how many children Grandma Loveday had with her - and mother came over together. They had a very bad storm when they were on the sea and it took them six weeks to come from England to this country. The ship lost its rudder and they drifted back and were buffeted by the storm and they never thought they were going to land. The sailors had to take turns working out on the deck of the ship. I have heard the folk say the sailors would run and hide and the officers would have to go down to their hiding places to make them go back to work.

L: Grandpa Loveday and Grandpa Blacker must have been in Pennsylvania at the time.

UW: I believe they must have been. I believe they went straight to Pennsylvania. I am not right sure.

L: Aunt Maria was born in Illinois. It is quite a way inland and her birth was not long after they came to this country. (Aunt Maria was born 25 May 1883 in Streator, Illinois. L.B.)

UW: Yes, it is. (Inland) I don't remember ever hearing the details of how they got to Illinois from Pennsylvania.

L: Was it their intention when they left England that they were going to come as far west as Wyoming?

UW: I don't know.

L: Anyway, they landed in Almy, Wyoming, for you were born in Almy. (Uncle Will was born 10 April 1886. L.B.)

UW: Yes. My brother Isaac, who died as a baby, was probably born in Illinois, I believe. (Isaac was born 12 October 1884. L.B.)

L: Our family records show that he was born in Almy, are they mistaken?

UW: They could be right. They probably are. Uncle Hyrum lived close by. They all lived close. Uncle Hyrum was one of Mother's brothers. We had a large house for the time. There were four, five or six rooms in the house.

L: Was it just a frame house?

UW: Just a frame house.

L: Was the house on the order of the old mining houses of the time which were owned by the Union Pacific Company?

UW: Yes. It wasn't a company house, however. It was on our own land and wasn't in the coal mining camp proper. We had to go about two miles, maybe further than that to take the men to work in the mines every morning. I remember when I was a little fellow, at times, I took the men folk to work and then I would bring the team back and then somebody would meet them at night. At that time they were working ten hours or more a day in the mines.

L: The location of the home was just across the river bridge where it presently is of this date of 1965? It is all meadow land now.

UW: Yes.

L: These three houses (Hyrum Loveday's Grandpa Isaac Loveday's and Grandpa Edward Blacker's) were all on the west side of the river?

UW: Yes, I wasn't born in the old family house. There used to be a concrete block house built right on the river bank just after crossing the river bridge. We thought then that Bear River was a very large river.

L: I've heard Dad talk about the big bridge they had to cross. This house you were born in - was it on your folk's property?

UW: Not on their property. I don't know whose property it was on. The folk told me that I was born in the concrete house and it was torn down. It wasn't there when I can remember.

L: It was probably a neighbor's home who could take care of Grandma.

UW: I suppose so. There were four or five families right in there - there was Reece Davis and there was a Bradshaw that had little places right in there - maybe seven or eight acres. I remember the time I was baptized, Bear River flooded. We had some low land and the water flooded the low land and I was baptized in this backwater from Bear River.

L: Was there any eventful thing when you were very young which you first remember? What are some of your first memories as you now look back?

UW: About the first thing I can remember is a time when I was sick, that would be when I was between five and six years old. I had what they called that time, inflammation of the bowels. They say now it is the same thing as appendicitis. The folk thought that I was never going to live. They sat up with me for nights and nights. I can remember that when I was getting better that I had a visit from a school teacher by the name of Luella Parkinson and she came to sit up with me. I remember one night as she came into my bedroom I turned over on my back and made out like I was asleep. I can remember she told Mother, "Will is having a little nap now and I won't disturb him", but I was there just playing possum. On my birthday, on the 10th day of April they had a party for me. Tom went down the string and picked up some of the neighbors' boys and girls and they had a birthday party. That was about as early as I can remember, because I remember that I had some presents on my sixth birthday. Some of them I kept. I think I may still have some of them yet for I cherished them all my life.

L: Now, you are up to when you were six years of age and time for you to go to school. The school house was how far away from your home?

UW: It must have been a mile or more away, you know, down to that old #4 red school house down there that they had in Almy. I don't know whether it was there when you were there or not.

L: No, I don't remember -. It wasn't as far down as the old red brick church?

UW: Oh, no. We used to walk, so it wasn't too far. We used to have a walking trail down the river - it was near where Uncle Ike used to live. I would say a mile away, maybe three quarters.

L: To the north but on the east side of the river? On what is now the old County road?

UW: Yes. Of course, at that time they had these little school houses - this school house was a pretty good size school for they had about three class rooms as I remember it.

L: Each mine had a school?

UW: I don't know about #7, but they had a school house down at #5 and #6. Like other coal camps, when the coal would run out, the camp would move away. There isn't anything there now but just a few farms.

At this point in the story let us put Uncle Will's verbal interview to the back burner, for there are other matters of importance which may be mentioned in an attempt to retain a degree of normal sequence.

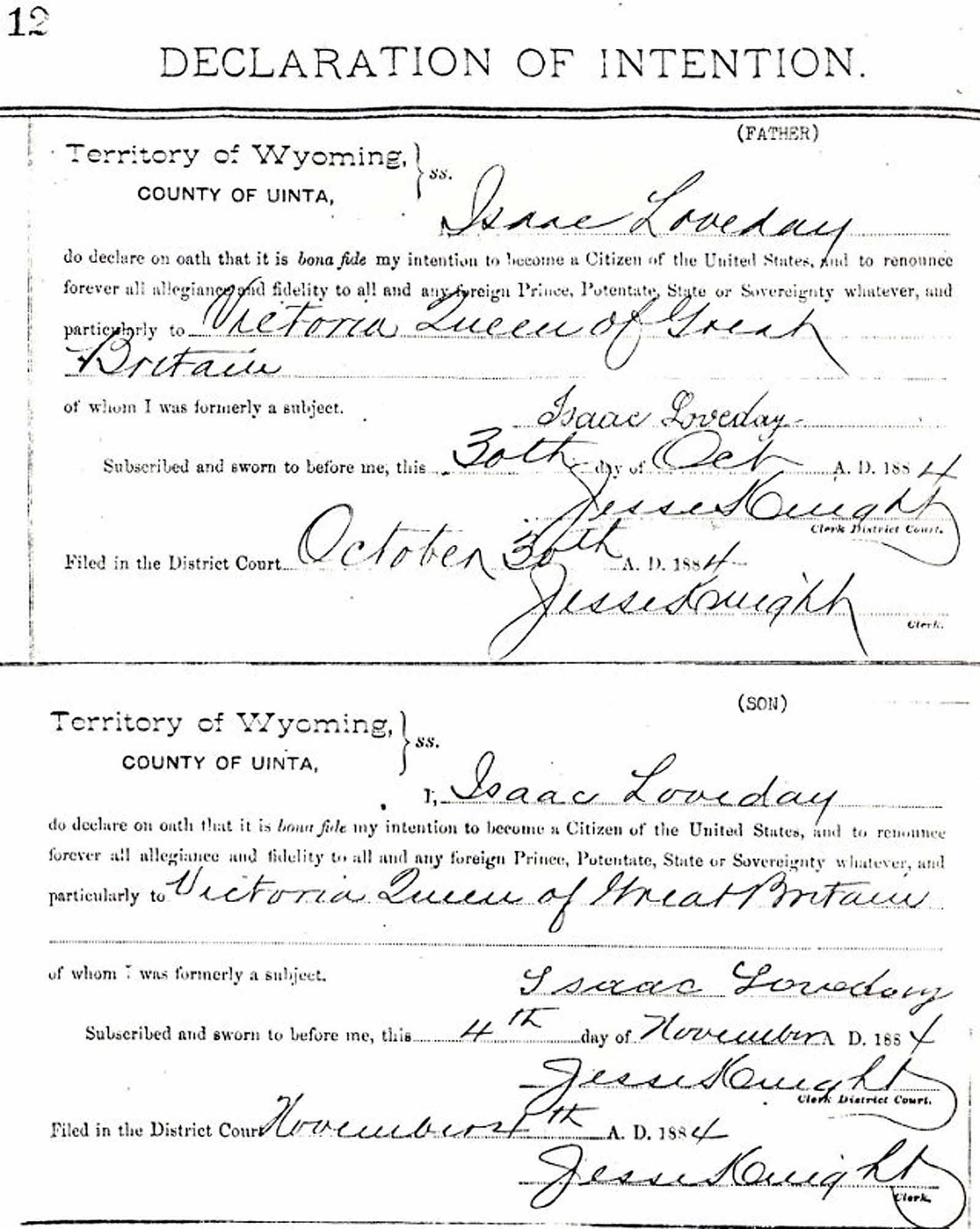

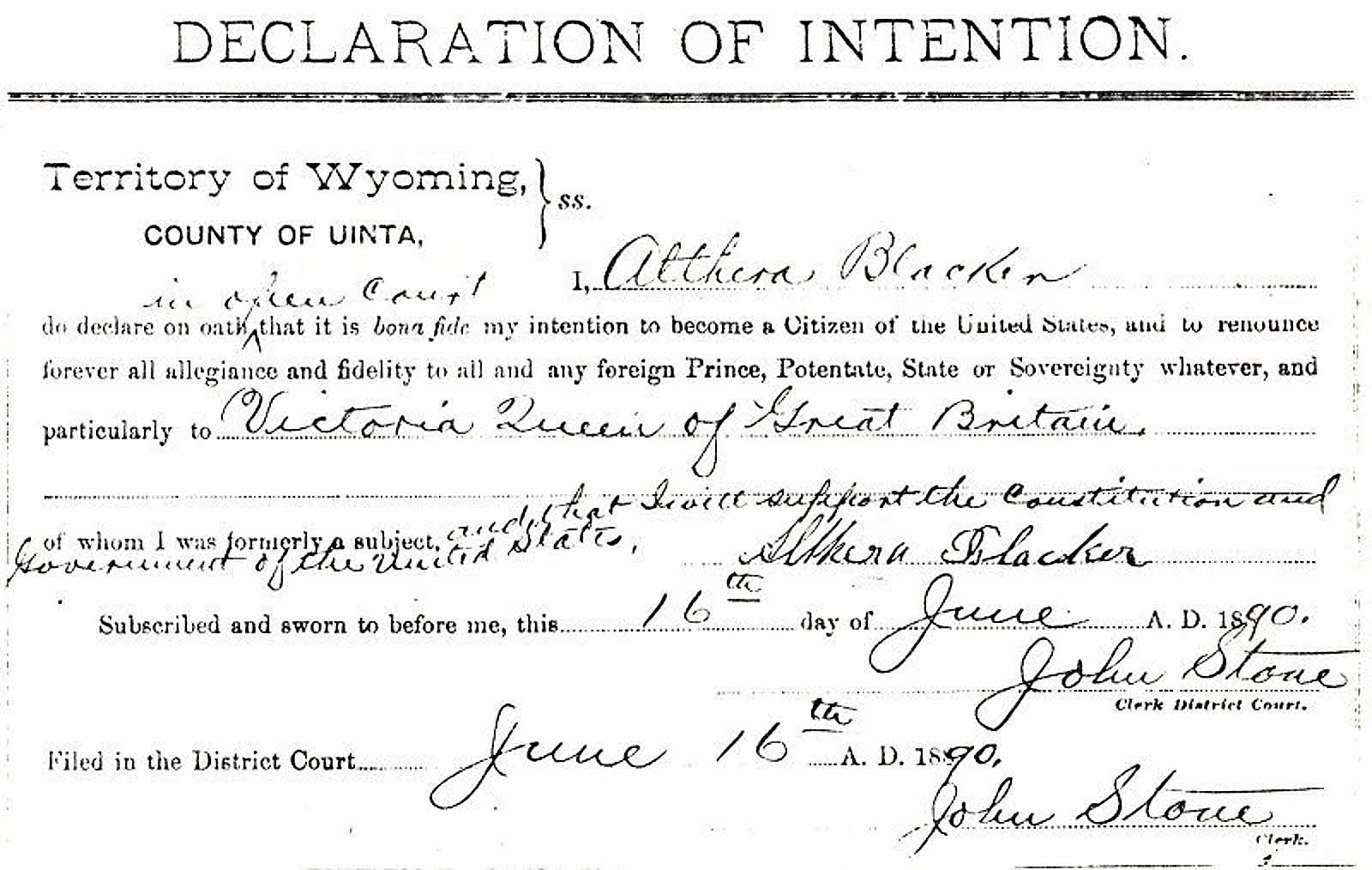

Of first importance may be confirmation of the fact that the families under discussion actually arrived in Almy. This can be done so far as the Loveday family is concerned. In an attempt to find confirmation, a visit was made to the Uinta County court house in Evanston in search of any type of affidavit to show if there were land records in the names of members of the families, and/or to determine if any attempt may have been made for a change of citizenship. Disappointment was the result so far as the Blacker family was concerned, but in the Clerk of Court's office, a record was found where Grandpa Isaac Loveday had declared his intention of becoming a citizen of the U.S. A photo copy of his declaration was obtained. This step was taken by him on the 30th of October 1884. Five days later, his two sons, Hyrum and Isaac Jr., on the 4th of November 1884, likewise, made similar declarations. There were no indications of their wives' intentions.

At a much later date, in fact, not until the 16th day of June 1890, this same request was personally made by Althera Blacker, but there seems to be no record regarding Grandpa Edward Blacker. We can't help but think there must be a record of such a step somewhere. If he made application while yet in Pennsylvania or even Illinois, there should be a record of finalization of citizenship having been eventually granted. This normally would have been processed in Uinta county, for it requires a period of a few years for citizenship to be finalized.

Isaac Loveday's declaration of intention to becoma a US citizen

Isaac Loveday's declaration of intention to becoma a US citizen

Althera Blacker's declaration of intention to becoma a US citizen

Althera Blacker's declaration of intention to becoma a US citizen

As to ownership of land in Almy, we were unable to find a record. After the family eventually moved to Star Valley, there is a record of him selling seven to eight acres, presumably this referred to his Almy holdings, and if this be true, it indicates, as earlier stated by Uncle Will, their farms in Almy were such a limited size.

Likewise, we found no record of Grandpa Loveday purchasing a home or land in Almy, but in checking the 1900 Census Record, the statement is made that he owned his home. There seems no reason to question the supposed fact that they settled with the intent of owning their property, but there wasn't room in their neighborhood for any sizeable acreage.

Their church activity was probably normal for the average family, particularly under the situation as existed in the Edward Blacker home. Grandma Blacker was the only member of the Mormon Church in Wales, and such was the status of the family when they arrived in Almy. Bishop James Bowns was the only bishop during the years of their Almy residence.

On the other hand, the Lovedays were all members, having been baptized while yet in Pontypool in Monmouthshire, prior to their moving to Mountain Ash. While we have found no record in Almy - the early records were burned - we have found a few occasions when Grandpa blessed and/or confirmed his grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren , as in the case of Uncle George's and Aunt Polly's older children.

Uncle George did not choose to be baptized until well after he and Aunt Polly were married - his baptism was in January of 1899, four and a half years after he was married.

The first Blacker baptisms in Almy were their two oldest daughters, Sarah Ann, when she was ten, and Mary, a couple of months prior to her reaching the eighth birthday. This family double-baptism occurred on the 19th of September 1886. Son Thomas, the first male Blacker of whom we have record to be baptized, was baptized on the 10th of September of 1891 on which same occasion daughter Maria was also baptized, a few months following her 8th birthday.

We are not aware what the final impelling or converting force was for Grandpa Edward to join the Church, but he was baptized on the 5th of June 1892. Uncle Will Blacker has advised us that even though Grandpa was not a member of the Church, he always attended meetings and always paid his tithing. Seemingly he was always an 'unbaptized Mormon' even before his joining. It simply is an impossibility for one to read and to listen with an open mind, having a desire to know the truth, to not become convinced that what the Mormon Church teaches is true. Facts are facts which cannot be long denied if one wants to know the truth. There is too much clear evidence that there has been a restoration for a knowledgeable person to deny it and, so, undoubtedly, long before Grandpa Blacker was baptized, he recognized the truth of the message.

In 1889 or 1890, the Almy ward building was burned to the ground with the cause of the fire not being known and a new rebuilding project was undertaken. We have not been told where the members met, but undoubtedly a hall of some description was leased until the new red brick building was constructed. This remained standing until the mid 1930s. By that time, the whole of Almy had become dismantled, so to speak, and when this writer appeared on the scenes, the ward had reverted back to branch status. The few of the branch were meeting in the small, two-room school house, rather than in the large, too expensive to maintain, brick church house. By 1937, the brick building had been completely leveled, with the materials of the building reused for the construction of new homes etc.

By 1900, the mines had all closed in Almy and a new mine or two had opened up in an area known as Spring Valley, about 20 miles east of Evanston. Some of the miners moved there, others to Cumberland, Sublett, Diamondville, etc.

The homes in Almy were either moved or torn down and the ground reverted back to pasture and meadows. So it has remained until the 1980s, when oil companies sent their vanguards in for oil finding in which, apparently they have been successful and the area is become again activated by those who are seeking another kind of 'black gold' from beneath the ground of Almy.

Again, let us return to the story of our family. Others of the living family may have known, but during the younger years of this writer's life it had not registered, if indeed I had heard that Grandpa Blacker had had a little experience in the political life in Almy. This has since been confirmed by Uncle Will Blacker.

Upon being accepted as the principal of the little Almy school in 1938, it naturally fell to my lot, when the keys were turned to me, to inventory supplies, books, etc. in the school's supply room. There had been a series of paper-back quarterly historical papers published by the State Department of History mailed to the schools for, particularly the teachers to become better informed on facets of the history of the state. They were under the title "ANNALS OF WYOMING". While I browsed through various numbers of the publication, there was little or nothing in them that was of value to the school children, so they were not put to use. It had to be at least a year later when one day, as I was glancing thru them, in noting the Table of Contents, I took note of a title, "Official Uinta County Visits Star Valley". The fact being that I was somewhat acquainted with Star Valley, for that was where I was born and lived my first twelve years, I turned to the article. To my great delight, I discovered some family history which I had not known. The portion dealing directly with Grandpa Edward Blacker will be copied verbatim:

"OFFICIAL UINTA COUNTY VISITS STAR VALLEY"

By John C. Hamm

At the first State election held under the Enabling Act on September 11, 1890, I.C. Winslow, John Sims and Edward Blacker were elected commissioners of Uinta County, Wyoming. John R. Arnold, present veteran jurist of the Third Judicial District, was elected county clerk, and the writer, John C. Hamm, was elected county and prosecuting attorney.

(By way of explanation, the date of the article was 1929, thirty-nine years after the event. Historically, thirty-nine years is a very brief space. To the youth looking forward, it is an interminable wilderness of time. When it is behind, we wonder at the swiftness of its passage. LB)

In those early days, Star Valley was an isolated frontier settlement of Uinta County in the first stages of subjugation by the hardy Mormon pioneers. No telegraph or telephone line had yet penetrated the primeval precincts of the lovely vale of Afton and Auburn, to apprize those quiet pastoral regions of the restless wagging of the outside world. No automobile had gotten beyond the fantastic vision of the early dreamers. The slow transport of the work team and the farm wagon was the vehicle of necessity. A spring wagon or a buckboard were luxuries.

No wonder those early settlers clamored for the improvement of their roads and bridges. Their butter and cheese and occasional meat products had to be brought to market over the mountain to Montpelier, then to Evanston, Almy and Red Canyon, - appalling distances when the means of transportation then in vogue are considered. There were no coal camps at Kemmerer and Diamondville, and the long hard drives over roads none too smooth, and fords sometimes dangerous, were tasks of real hardship.

So it was determined in the summer of 1891 that an official trip of investigation by the Board of Commissioners was necessary, and John Sims and Edward Blacker were designated to make the inspection with the cooperation of their clerk, Mr. Arnold.

There had arisen some dispute over the ownership of a calf in the vicinity of Afton, and the prosecuting attorney was called upon to investigate the affair in the local justice's court to see if a felony had been committed. Hence the all around utility and economy of the official visit.

This August representation of the dignity of official Uinta County, the first of its kind in the history of the valley, drove a team of cayuses hitched to a spring wagon They were piloted by Archie Moffatt, a noble son of that virgin land, who was returning to his home in the Valley, after having delivered a load of butter and cheeses to residents of Evanston, Almy and Red Canyon, who had become acquainted with the excellence of those products of the early valley days. On the trip, Official Uinta camped in the open, slept under the wagon or elsewhere, as suited convenience or necessity.

On the way out, the route chosen was up the Thomas Fork to determine whether this were the more feasible site for a county road into the valley. This route brought us out on the ridge at the southern extremity of Star Valley where we intersected the old Lander Trail at what was early called Sublette Pass." (Annals of Wyoming, Vol 6, No. 1 and 2, 1929. Pp. 192-3).

I was saddened the day I first read the article, but in the intervening time - nearly 45 years - I have been led to multiply my disappoint to where it seems a crime that Mr. Hamm failed to write on further word of their Star Valley experience, but rather, permitted himself to spend the entire balance of his article in reviewing - much imaginative - of what had earlier transpired at the historic spot he referred to, the aspen grove which surrounded the junction where the Old Lander Trail bisected the proposed road into Star Valley. The entirety of this story which was so interestingly started, resulted in what, in history past, his mind's eye could see. For our purpose here the writer tells us nothing further which could be applicable to our story. He leaves us at the verge of the Valley. Why his title? And yet, we are grateful for him having opened to us another chapter of Grandpa Blacker's life. We have learned enough that we, too, like Mr. Hamm, can use our 'mind's eye' in tying together the past with then, then, future. Well over ten years ago (1971) this writer had occasion to dwell upon the very subject at hand in writing "The Story of Thomas and Hettie Wilkes Blacker". Again is the copying verbatim:

"BORN OF GOODLY PARENTS"

It is interesting to note that the write (Mr. Hamm) mentioned the cayuses which nomenclature may not altogether fit the team of horses being used. As we now envision in our minds this trip, we can wonder whether or not the spring wagon and team of horses belonged to Grandpa Blacker. He had such an outfit and it seems more likely that one of the commissioners, if he had possession of such equipment and horses, would use it. Just a possibility.

The above quoted paragraphs of this historical visit can stir in our imagination, a dream that must have entered into the mind of Grandpa Edward as he viewed for the first time lovely Star Valley, which later was to become his home. Already he had tired of the mines, not only tired of them but, perhaps, more particularly saw the handwriting on the wall that he would soon be forced to leave his employment in them. Undoubtedly he dreamed of the day when he would be able to take his family, particularly his sons from the 'mines of death' that they would not have to spend their lives working in the dust of the coal pits.

Upon his return from this first trip to Star Valley, we can image the scene in the home of that family as they gathered that evening around him in the flickering light of the well-trimmed kerosene lamp. Grandma Althera was, that night, a relatively young 39 1/2 year old mother of eight, with her ninth to be born only five months later. All eight were not living, for sadness had come into their home seven years before, when her little two year old son, Isaac, just older than her then, three month old son, William, had died. He had been buried in a little grave in the newly purchased lot in the Almy cemetery some two to three miles to the north of their home.

Listening to the report of their father that night, were Edward George, age 17; Sarah Ann, age 15; Mary, not to be 13 for another five months (actually Mary may not have been home that evening for she was living with her grandparents, the Isaac Lovedays, nevertheless, she certainly belonged to the Blacker family); Thomas, 10 1/2; Maria, a couple months past eight;

William just past five and baby Merintha just at three years of age. Perhaps the two youngest found more interest playing on the board floor with their playthings, or perhaps, they had been put to bed by their older sisters, but undoubtedly, those from eight years and up were listening with eyes and ears wide open.

The first evening of this supposed home family meeting was too early for plans to have materialized. This was a night for dreams - for discussion - to see the reactions of family members who had no way of envisioning the Valley excepting seeing, in their minds, the picture Grandpa Edward could portray to them. The intent, at this point in the story, is not to cause the reader to think the family was ready to pick up everything and make the move to star Valley the next morning. This was not the case, but undoubtedly, was the beginning of planning for a future move. Actually it was not for yet another five to six years before the actual moving transpired." (Born of Good Parents, pp. 7 & 8).

Life, undoubtedly, went on much the same as it had since their arrival in Almy. Again we repeat that little Isaac, when but two years of age, passed away and was buried in the Almy cemetery in 1886. Nearly five years later, his great-grandmother, Ann Powell Danks, wife of Peter Danks who had been buried in Pennsylvania in 1873, was buried not far from Isaac's grave. After the Blacker family had moved to Star Valley, Isaac's grandmother, Grandma Mary Danks Loveday passed away 14th of April 1902, and was buried in the Almy cemetery next to her mother just mentioned, Ann Powell.

With Grandpa Isaac Loveday, having become a widower again, as just mentioned, this seems to be an appropriate place to copy, verbatim, the article relating to him in the book, "Progressive Men of Wyoming" referred to much earlier in this history. Actually, the representative of the publishing company who printed the book, the A.W. Bowen & Co., of Chicago, Illinois, apparently solicited the many subjects of the volume from over the entire state of Wyoming which, undoubtedly, was a business project. Undoubtedly, the purchase of the completed volume was a prerequisite to the luxury of having a biography included, and yet we are pre-supposing. If Grandpa Loveday obtained a book, it has probably become a treasure in the home of one of his descendants. The account follows:

ISAAC LOVEDAY

One of the most skillful and prosperous farmers in Uinta county is Isaac Loveday, who resides five miles west of Evanston. He was born in Wiltshire, England, September 14, 1821, and is a son of Solomon and Mary (Godin) Loveday, the former of whom was a son of Jonathan and Sarah Loveday and was a farmer by vocation. Isaac Loveday, naturally enough, was reared to agricultural pursuits, and his youthful days were so closely occupied by his duties on the home farm that little opportunity was afforded him to acquire an education; nevertheless, he attended the common school for a season or two and learned what little was absolutely necessary for him to know in carrying on the calling which was to be his life work.

For some years he worked as a farm hand for his neighbors in England, and also passed a few years in Wales, engaged in the same capacity. In 1880, Mr. Loveday came to the United States, with the hope of improving his circumstances in life, and in this hope he has not been disappointed, as from the start he has met with encouraging success. For the first year after his arrival in

America, he worked on a farm near Honesdale, Pa., and then went to Illinois, where he was employed in the same occupation about a year and a half, when he came to Wyoming and entered the ranch on which he still lives, west of Evanston.

Four generations: Isaac Loveday in center, daughter Althera left, grandaughter, Mary right and Mary's daughter Arvilla

Four generations: Isaac Loveday in center, daughter Althera left, grandaughter, Mary right and Mary's daughter Arvilla

The marriage of Mr. Loveday took place in Wales on August 5, 1849, with Miss Mary Danks, a daughter of Peter and Anne (Powell) Danks, natives of Wales, and to this union there were born seven children, namely, Hiram, who is married and who is farming in Idaho; Merintha Althera, married to Edward Blacker, a farmer in Star Valley; Kemmel, living in Diamondville; Fannie E., wife of Thomas Lewis, of Cannonsburg, Pa.; Thomas, who was born in Wales, February 25, 1859, also died in that country when nineteen years of age; Isaac, who is a farmer, is married and is living in Cache Valley, Utah; Sarah A., who was born in Wales, October 25, 1865, and there died July 1, 1866.

Mrs. Mary (Danks) Loveday was born in Wales in 1832, a member of the Church of the Latter Day Saints, her remains being interred in the cemetery at Almy, Uinta County, Wyo. Of the Church of the Latter Day Saints Mr. Loveday and his surviving children are also faithful adherents, wherever they may live. Too much credit cannot be given to Mr. Loveday for the energy and perseverance he has exercised since becoming a resident of Wyoming, and his fortune is of his own making. He is a good citizen and is greatly esteemed by his neighbors and from such men as he, it may be said, the greatness of a state is derived". (Progressive Men of Wyoming, pp. 867-68).

It would seem that Grandpa Loveday deserved every plaudit the writer of the above article wrote of him, despite the fact that all his possible holdings in Almy would have been acres that could have been counted on his fingers and, perhaps, not impossible to have been able to have confined to one hand. Flattery was a sales gimmick on the part of the salesman, as can be confirmed by other biographies in the same volume. This is not to demean Grandpa Loveday. Members of the family who were very well acquainted with him have spoken highly of his 'green thumb' and of his meticulous gardening habits and practices which made it a crime on the part of a weed to show as much as a green leaf within the garden fence line. Other than a good-size garden spot at his home in Almy, he may have had a small amount of soil which provided pasture for a cow or two. The publisher's representative didn't overestimate - Grandpa Loveday was as successful as anyone could be under the same circumstances, probably more so than most would have been.

Uncle Will Blacker, who lived neighbors to the Lovedays, said their health was not good, especially Grandma Loveday's. Shortly we will return again to our interview with Uncle Will who will advise us of their need to have Aunt Mary Blacker (Wilkes), during her girlhood years, spend all her time with them, rather than with her own family.

Relative to the Blacker family, let us return to their story to see what is transpiring. To do so, more quoting from "Born of Goodly Parents", this following their decision to move to Star Valley:

Grandpa Edward's decision to move his family to Afton came too late to be able to take his entire family with him, for his oldest daughter and second child, Sarah Ann, married Archibald Durie Nisbet on the 30th of June 1895, and her brother, George, married Mary Bailey on the 31st of July of the same year. Neither of these couples ever moved to Star valley for permanent homes, but remained for the time being in the areas of the coal mines.

Grandma Althera Blacker's parents, Isaac and Mary Danks Loveday were in poor health at the time to which we are referring and in making plans to leave Almy, it was concluded, for the present at least, that they would not follow the Blacker family to Star Valley. They would remain in Almy, but they were not to be left without help. Aunt Mary, then seventeen years of age, was selected to remain with her grandparents. Actually, she was the only one of the family who, due to age and experience, would be able to carry such a responsibility. Aunt Maria, the next in line for such a responsibility had just reached thirteen years of age, and therefore was too young. Also, it may have been Mary's choice for she had stayed with her grandparents a goodly share of her girlhood years, probably because of the help she could give them. Also, because of there being nine children in the family, until the marriages of 1895, plus the two parents, even though it was a five or six room house, they would have been crowded.

With Mary remaining in Almy and the two children having married, there yet remained six children who went with their parents to Star Valley. What prompted them to start their move in the fall of the year 1895, we don't know. It seems that it was the wrong thing to do and even Providence seemed to step in and hinder them from completing the trip. Two friends of Grandpa Blacker, Archesio Corsi and Archie Moffatt, from Star Valley, had been to Almy and nearby settlements with their freight wagons of cheese, eggs and farm produce. They were returning with their wagons only partially loaded and agreed to take the Blacker family's furniture to the valley. They were to lead the way and Grandpa and his family were to follow shortly after. As the family reached Randolph, Utah, a settlement some thirty miles from Almy, Uncle Hyrum, then just four years of age became seriously ill. It was felt wise to return to their home in Almy into which Uncle George and Aunt Polly had moved upon the departure of the family. With their furniture and much of their clothing on the way into the valley, they were, indeed, much handicapped, but felt that out of necessity, they would have to remain in Almy for the winter." (Pp. 8 and 9).

Perhaps, at this point in the story we might pause to review some of the actual concern the family had endured with their mining occupation. As stated, the decision to leave Almy permanently did not develop over night. It was as though the handwriting was on the wall. Coal mining had been good to the family, for it provided a living but it had a price. How long the problem had been with him we are not prepared to say, but we are aware that it had been showing its toll through the years and the Blacker family was not to be deprived of its share of such problems.

Mine explosions oft times caught groups of miners unaware and brought suffering and death to many and the Almy mines were no exception. During these years of which we are writing - the first half of the 1890s - Almy had reached and probably passed its zenith of population as well as its overall potential. Coal mining camps are sometimes known to be short-lived for the simple reason that their coal supply is not inexhaustible. Such conclusions were foreshadowed, for by this time, the first mines open as early as 1869 had long been closed and new ones opened, going north along the valley's east hills where the last of the coal veins were located.

Jumping ahead in Almy's history to 1900, its mining days had about ended, and the whole populous had to move on - not all in one day, but gradually. New mines were being opened up in other area such as Spring Valley, where for but a few years there was a coal supply. The Cumberland, Glencoe and Kemmerer areas opened up. While the Rocky Springs mines were opened as early as the Almy mines, their supply was greater and remained in production much longer. Coal mining in Superior, Wyoming, a few miles northeast of Rock Springs opened - each of these mentioned coal towns becoming an eventual home of the next couple generations of the Edward Blacker family, particularly son George's family and, for a time, daughter, Sarah Ann's family, however, the latter soon pulled away from that occupation.

But, back to Almy: Probably the one greatest single event of discouragement to the Edward Blacker family, beyond the already recognized health factor, was the devastation resulting, not in the mines that the men folk of the family were working in, but that of a neighboring mine - Mine #5. On the 20th of March 1895, at about 5:45 p.m., just a few minutes before the day shift was to leave the mine and the night shift to come on, the regular routine of the mine was interrupted by three devastating blasts. Flames and dust shot out of the mouth of the mine, which sent timbers and other debris followed by billowing smoke which could be seen all over the valley. This which could be seen was but evidences of what had transpired lower in the mine. The blasts were so severe, that so far as is know, every man who was in the mine at the time was killed. The catastrophe occurred, as stated, but a few minutes before the day crew was to leave the mine and prior to the night-time crew entered. Many and many are the stores told including the reports that some of the usual day crew had felt impressed to not work that day or, of some, who had left early.

Few families in the community were not affected directly, and seemingly, the Edward Blacker and Isaac Loveday families, so far as is known, were among the few, having no immediate family members working in #5.

Following the blasts and as soon as the flying debris and dust and smoke cleared sufficiently, the men outside the mouth of the mine, including many of the on-coming shift who would have been victims had the blasts occurred but a few minutes later, at the risk of their lives, formed rescue teams and entered in search of victims. Sixty-two casualties - husbands, fathers, brothers, sons and close relatives - few families of the community escaping relationship, and probably no family escaping who did not have close acquaintances and friends.

The coal company did all they could to assuage grief, but this kind of grief cannot be taken from survivors of such calamities. The company provided caskets for the dead and prepared the bodies for burial and then the dead where taken to their homes, or homes of relatives or friends, to await the funerals. Some of the dead were shipped out of town, some to nearby Evanston and other places for private funerals.

Funeral services were held in the Almy Ward church for thirty-three who were to be buried in the local cemetery. Almy was very much a Mormon community and from Church headquarters in Salt Lake City came announcements of their deep concern. President Wilford Woodruff was president of the Church at the time and the First Presidency sent the following official representation to the funeral service: Joseph F. Smith, Franklin D. Richards, Seymour B. Young and Edward Stevenson.

With thirty-three caskets, there was little room left on the inside of the chapel, so most of the mourning families and, certainly their friends, were seated on chairs forming rows one behind the other. Bishop James Bowns, the Blacker family's bishop and probably the bishop to most of the decreased, conducted the service. Other officials, including the General Authorities, sat behind and used the pulpit in proper turn. The choir leader was James Hood. In song and sermon the grieved were comforted as best as possible in that funeral setting. By far the majority of the mourners, due to lack of space, experienced the funeral from outside the building.

After the services the caskets were again placed in the wagons and taken to the waiting graves, most of them being in the Almy cemetery.

In addition to this single devastating event which affected decisions of mining families who were on the verge of 'having enough', with the Edward Blacker family fitting into that category, there were other mine hazards. Included were the cases of dangerous gases, heavier than air, which found pockets in which it accumulated and often trapped and poisoned men. These traps of death were more sudden in taking their toll, while miner's consumption, such as Grandpa Blacker was experiencing, was just as much a killer, but much, much slower. It would take many months and years to disable a man to the point that he had to leave his employment. In addition to this resultant end, the latter would torment him day and night for years to come, only to be relieved by a merciful death, which would eventually bring relief to the sufferer.

One can quite easily imagine what concern, what grief and heartache would become the lot of one's loved ones as they witnessed him having to struggle to get air into the closing and wasted-away portions of his lungs which are so necessary in transmitting life giving oxygen and other air ingredients into the blood stream in order to sustain life. What price to pay for the privilege of employment! But a means of livelihood was essential - a living had to be provided for one's family and in coal mining camps other types of work are very limited.

The decision to move had been made, in fact they had already made a start to go to Star Valley, but circumstances brought them back for the winter. Undoubtedly, they may have given the anticipated move a second thought. It was to be farming and stock raising at approximately the same elevation they had been accustomed to in Almy. One hundred sixty acres this time, not the small six or seven acres they had had for the last eleven or twelve years. Even so, their little acreage in Almy could be classified as a 'luxury' acreage. Wages from the mine provided their living - not the acreage - even though it may have supplemented those wages just a little.

Again, back to some direct quoting:

It was not until April of 1896 that they again started for the Valley. They had experienced a heavy winter and made the trip in a sleigh with three horses, two pulling the sleigh and the third being led behind. After a very eventful trip, in which their sleigh and horses had to be left on the road due to the horses slipping into deep drifts, and being unable to get up, the family walked for hours to reach a farm house near the entrance of the Valley. This walk was almost more than some of the family could endure, but they did reach the farm house. With the help of the mailman, who came along later in the day, the horses were again hitched to the sleigh and the family later proceeded to the Valley reaching Afton on the 10th day of April 1896.

This family picture was taken in 1895 just prior to their moving to Star Valley.

Aunt Sarah Ann and Uncle George were ready for , or just previously married.

Mary remained in Almy with her grandparents. Only the six younger children migrated

to Star Valley with their parents. Front standing: Hyrum, Fannie Seated left

to right:Merintha, Althera, William, Edward, Maria. Back row: Sarah Ann, George,

Mary, Thomas Kemuel the youngest child was born two years after this picture

was taken.

This family picture was taken in 1895 just prior to their moving to Star Valley.

Aunt Sarah Ann and Uncle George were ready for , or just previously married.

Mary remained in Almy with her grandparents. Only the six younger children migrated

to Star Valley with their parents. Front standing: Hyrum, Fannie Seated left

to right:Merintha, Althera, William, Edward, Maria. Back row: Sarah Ann, George,

Mary, Thomas Kemuel the youngest child was born two years after this picture

was taken.

With snow yet on the ground in the valley they drove to their new 160 acre snow covered farm to the little dirt roofed two-room cabin which was to be their home. No one had been living in the house during the winter, into which, we presume the freighters had put their furniture several months before. With no one having been around, it was necessary, even in April, for them to shovel the snow away from the door in order for them to step down into their home.

They were now in the new world! As we look back from our vantage point three quarters of a century later (at this writing an additional more than 10 years. L.B.) it seems that it would have been a frightening world to have awakened to the next morning. Eight souls for which to provide and the pay-check cut off. No livestock on which to depend on for food. Three horses, yes, and horses were necessary, but there was no feed in the pastures for it was yet too early for grazing. Maybe Mr. Stewart, the original homesteader from whom Grandpa purchased his homestead right for the sum of three hundred dollars for the 160 acre farm, had left a little feed in the form of hay. We don't know, but maybe he didn't. The family situation was noticed by neighbors. Coming to their rescue was Oz Gardner, a neighbor one-half mile away who loaned the Blacker family a cow and enough hay to feed it. This indicates that, perhaps, there was little or no hay for the horses.

It was not long until it looked as though the mistake of their lives had been made. Wife and mother, Althera, could probably be the most responsible in the move for she wanted freedom from the fear she had lived with as to the safety of her men-folk in the mines. She had also observed the safety encountered and the satisfaction derived from working with the soil, from the life of her father who loved the it. Too, in all likelihood, even though she was the mother of ten children at the time, she wanted her boys in work other than what they seemed destined to do if they stayed in Almy. Now she was free of that concern, but she had been so accustomed to a weekly or monthly income from the work of the mines, that she could have overlooked the security that working for 'old King Coal' had given them. Just as regularly as the clock went around was income being received. Perhaps it had not been all she needed, but there was some and it provided security. She could go to the company store and draw groceries even upon unearned money. With work, there was food and clothing for her family. Had she thought what would happen with the pay check cut off?

We are sure she had but maybe they didn't realize how seldom income would come in when they got to Star Valley. It is true they could milk a cow, but the cow had to be fed and the cow could die. They could plant a garden and live from its fresh, healthful, tasty vegetables and fruits, but there were the mice, the squirrels, the gophers who probably liked vegetables better than humans. If the vegetables were there, they came easier to the rodent than to the caretaker of the garden. There were the insects, the plant diseases which had to be contended with, and most seriously of all, there were the weaknesses of Mother Nature - the lack of water in the dry seasons and, particularly for Star Valley, the frost. It is not uncommon there to have frost every month of the year. Yes, Jack Frost seemed to enjoy creeping down from the tops of the high surrounding mountains during the nights in his playful gesture of tingling the ears of humans and plants alike. Also, as the warm days of summer came with their soft, and sometimes not so soft, breezes the ground steadily lost its moisture and in order for the plants to thrive, moisture had to be provided. Ditches had to be plowed from one high area to the next in order to run the clear cool water onto the dry soil. This became a neighborhood chore, for all the farmers in one area would join together to make a main ditch leading all the way from the headwaters near Swift Creek Canyon a few miles away. The water from there had to be apportioned among the four or five ditches leading to the various areas of the valley and this required engineering and maintenance. When the water in the main ditch eventually reached the private farm itself, then it remained up to the farmer to distribute it from one knoll to the next and this, in and of itself, was a little engineering feat of its own. The principle of irrigating was that if water could be gotten to the high places, it could be led to trickle down the slopes so that every blade of grass or grain would benefit from the moisture.

Grandpa Blacker was not a farmer, nor a cattleman, nor a horseman and it seemed it didn't come easily to him. Also, due to the fact that his health was far from good, as mentioned earlier, a great amount of the farming program on the new farm fell to the boys. In these early Star Valley years, Dad (Thomas) became the head engineer. He was sixteen and the next in line son was William, then between ten and eleven years of age.

It is questionable that everything went as smoothly as it might have done. Such is usually not the case with farmers who are poorly equipped with machinery and experience. How soon they bought a cow of their own we don't know, but it is not likely they got into the milking business in a big way overnight. Things like this take time and in the meantime income became a nightmare, not so much for it but for the lack of it. Probably more concern was felt by Grandma Althera than by anyone else. First it was difficult for her because it was her disposition to become concerned, and secondly, she was faced with real problems, as has been explained.

No housewife would find her lot easy, who had to house her family of eight in a two room log house. The floors were of rough boards and these are not easy to keep clean under the best of conditions. There couldn't have been much floor space left to view with the furniture and eight pairs of shoes standing on it. Bed-down time was undoubtedly a challenge, for most of the children had to sleep on the floor. It so happened that the former owner had built a small shed, which technically was called the milk-house. It was a short distance from the house to the north toward the corrals. This also had a dirt roof, but the roof was low. In envisioning how improvements could be made, the family decided that if the building could, in some manner, be attached to the house, it would make more room which was so badly needed. So planning and engineering were put to use and it was decided that if the roof of the milk house could be raised to the level of the roof of the house, and the several-foot space between the two could be enclosed and roofed, the added section would supply at least a couple additional bedrooms. How soon this project was completed we have no way of knowing, however, it is very possible it was not done for two or three years following their moving to the Valley. (Born of Goodly Parents, pp. 9-11.)

Let us get some 'on the scene' comments from Uncle Will Blacker who was ten years of age when the trip from Almy to Afton was made. The following direct quotations comes from the taped personal interview in July of 1965, part of which has previously been quoted: (The initials, L. for Loyn; UW: for Uncle Will.)

L: "- - - Now, you were getting up to about the time your folk were beginning to talk about moving to Star Valley.

UW: Well, yes, I remember when Dad was elected county commissioner. He and our neighbor, John Sims, were on the commission and they went over to Star Valley with a team and buggy and they put that road thru from Afton thru Nield String, over to the west hills. It didn't go all the way over, but just to the road where it turns off to Fairview. Dad and Sims forced the road over to the west hills while he was on the board of commissioners. I was just a little boy, but I remember about them going and then about this time Dad had been over, and we had Archie Moffat and Archiso Corsi who used to come out to Almy and peddle cheese, butter and eggs and sell to the mining camp. They used to buy them in Star Valley and bring them up to Almy with horses and wagons and they were good friends of Dad's, and Dad had been up to the valley, so he decided that he would like to go there, because he had been hurt in the mines two or three times and he decided he would like to do something different than just mine all his life. And the funny thing about it was that when they decided to go over there, that Archiso and Brother Moffatt loaded on part of our furniture and took it in their wagons. They started and we were to catch up with them and meet them at Randolph. They used to stay at Andrew Kennedy's place and a Mrs. Morgan's, whose husband got killed in number Five explosion and was a neighbor of ours. After we got abut half way down to Randolph (Randolph was about 30 miles north and west of Almy, L.B.) my little brother, Hyrum, took sick and we had tot urn around and go back. We had to go back to George's and Polly's who now were living in the old house. We went back and stayed all winter with them, but the bad thing about it was that so much of our furniture and some of our clothes and the girl's dresses were gone so were in a heck of a shape. (Chuckling).

L: That was in the fall you were attempting to move, and you stayed until the next spring. Do you remember the trip over?

UW: Oh yes, it was just in the spring of the year and we were in a sleigh and at first we didn't have any trouble. We used to go to Randolph and stay all night and then sometimes we would go to Garden City. Dad had some friends in Garden City and the we went to Montpelier where Aunt Sarah Ann and Uncle Tom (Danks) used to live.

From Montpelier to Star Valley we had a little trouble. Father was a 'green-horn' about horses. He didn't know much about horses and it was in the spring of the year and the roads were getting pretty soft and there was a lot of snow and one of the horses stepped off the road. Of course he couldn't get up, for when he fell the other horse pulled the sleigh right onto him and he couldn't get up. Instead of us going to work and pushing the sleigh back off of him so he could get up, Dad just rolled him over and rolled him down in the gully and he was clear out in the snow then. He couldn't get up - I remember then - we had a rope and tied the rope onto him and to the other horse. In pulling him, with his struggling, he pulled the other horse down. We had three horses - we were leading one horse behind us. Instead of staying with the sleigh like we should have done, why, we hit out to walk and we walked for a long ways and we got over to Nield's ranch - it took us all day. Fannie and Hyrum were little tots and - I'll never forget - Mother and Dad carrying these two little kids. Dad carried Hyrum on his back. Where he was holding him on his legs, after we got down to the mail station we stayed for a couple of days for Hyrum couldn't walk. The mail man, when he came along, found the horses off the track - the sleigh was on the road - and he made a road around the sleigh and he stopped and brought our bedding and he brought our grub box and brought it to us where he used to change horses.

L: Would that have been what we knew as the 'half-way' house?

UW: No, that was past the half-way house. It was closer to the valley, down where the old Brooks place was - the old Cousin's place.

L: You were then getting close to the Valley?

UW: Yes, we walked and we walked and we walked and it was snowing. The wise thing would have been for us to have stayed where we were until help came. When the mail man came he changed horses and he drove on down to town, so Dad told him to send somebody up to help us, so Hy and Sam Kennington came with a team and went on and got the horse up out of the snow and brought our sleigh down to us and then they took us down to Star valley. I remember when landed in Afton it was on my birthday - the 10th of April and I was ten years old.

L: That would be 1896. Well, Grandpa had been over to the valley and proved up on a homestead?

UW: He didn't take up any land, but he bought a homesteader's right. I have heard Dad say that he gave him $300 for the homestead right of 160 acres.

L: That was the old home two miles north and one west of Afton?

UW: It was known as the Stewart homestead for a long while.

L: For the benefit of those who don't know where the old Blacker home is, you were a mile and three quarters north of Afton and one mile west.

UW: Yes

L: At the time there were 160 acres and the log house was on the place?

UW: When we got to the house we had to make steps thru the snow down to the house.

L: Was it just a two room log cabin?

UW: Just two rooms and how they ever got along with the family with just two rooms. I can remember when I was just a little kid, how Mother used to cry because there were pretty hard times in Star Valley at that time. There was no money. Father was used to getting a pay check from the mines. When we went down there, there was nothing coming in and mother used to cry because we didn't have any money - we just didn't have any money for there wasn't any. I remember when we went to Oz Gardner's place to help him put up some hay on shares. When the hay was sold, Dad sold it for $2.00 per ton and we had to take a 'due' bill - that is an order on the store because they didn't have any money. When they sold anything they had to take it out on a 'due' bill on the store for there was no cash over there. This summer when we were putting up hay, I got run over with a load and I got my hip broke. It was never set right and I have been a cripple all my life from that time on.

L: What age were you then, Uncle Will?

UW: Between eleven and twelve years old.

L: That was the next year after you moved.

UW: Oz Gardner was very good to us. He had some cows and after we got over to Star Valley he gave us a cow to milk and he furnished us some hay to feed the cow until we could get started ourselves.

L: When you got there, was the land on the farm under cultivation? Had it been plowed and developed?

UW: Some of it had been cleared.

L: A good share of that farm is down in the meadows, that is, pastureland down on the river bottom.

UW: Yes, there were springs down in there. Some of the land was clear, but I remember us going out and clearing the sage brush off after it was plowed up.

L: Now, Grandpa Loveday went over with you? Or, at least, he got over there later and lived with you?

UW: They were in Almy and they stayed there until Grandmother Loveday died - just how many years it was, I don't know. It wasn't too long because we were still in the log house. We actually stayed in the log house a long while. The first man who built the log house built a milk house just a little ways away from the house. It had a dirt roof on and (the folk) they raised the roof up on the milk house to be even with the roof on the house and they connected the two houses together which gave us more room. When we went down there first there were quite a few of us and they just had the two rooms. I remember they had to make beds on the floor every night for us kids to sleep because they didn't have room for beds.

L: The floors, of course, at that time were probably wood and I suspect it was just a board floor.

UW: Yes, just a board floor but with the other rooms connected on. Mother lived there until Dad died.

L: That was in 1910 when he passed away.

UW: Yes.

And so, to retain a degree of sequence to the family story, we leave Uncle Will's taped interview of July of 1965. His further comments will be picked up as a continuation of this story shortly.

It had to have been during the winter season of the next year or two following their arrival in Afton - 1896 - that our father, Thomas, returned to the Evanston area for work, undoubtedly, to supplement the little income the family had been receiving from the crops and livestock of the farm. Unquestionably, as the first two or three years passed some progress was made in stocking the farm with animals such as a few cows, chickens, pigs, etc. It probably was not more than a winter or two at most that Tom returned to the Evanston area, but it is known that he was employed as a guard on the Union Pacific railroad. At that time, the company was drilling the Altamont tunnel thru the hills south and east of Evanston, which actually shorted the main line of the railroad several miles.

We do not know the full particulars of the guard job, however, there was a small-pox epidemic and part of the time the guarding had to do with matters pertaining to it. What other guard work needed being done is not known. There very well could have been other work than guard work, which our father, Thomas, did while away. It is of interest, that he had a guard companion whom he, undoubtedly had known before, for he too, had grown up in Almy. The companion, Herbert Brown, later married and had a daughter named Mabel Brown to whom Thomas, years later - nearly forty years later - became father-in-law. A small world!

Back in Star Valley, time proved an ally to the Blacker family and conditions improved. More prosperous conditions than were evident the first two or three years came as a result of their labors. Child number eleven arrived on the 28th of October 1897, and he was named Kemuel from a family name on his mother's side.

The years 1898 and 1899 passed and then the turn of the centuries - the nineteenth passed into history and the twentieth century was born.

As it comes to all, back in Almy, as had already been alluded, death came to Grandma Blacker's mother, Mary Danks Loveday on the 14th of April 1902. She was laid to rest in the Almy cemetery at the side of her mother, Ann Powell Danks, and near the grave of little two year old, Isaac Blacker. Her passing broke up the home-life of the Isaac Lovedays and brought to the Blacker home in Star valley, their daughter and sister, Mary, who had remained in Almy to assist her grandparents. Grandma Althera's father, Isaac, now eighty-one years of age came to Star Valley to spend the rest of his life with a favorite daughter.

Picture taken while visiting the Brooks home in Wyoming around 1906. Will Blacker with shot gun, Ed Wilkes with guitar, his wife, Mary Blacker Wilkes and baby Arvilla on chair. Kneeling front: Mr. Brooks with sheep and dog, Thomas Blacker in hat near door holding 9 month old, Theadore. 2 ½ year old Leroy standing on stool with feet just above sheep’s back Back: Mrs. Brooks in doorway. Hettie Wilkes Blacker at front doorway with high crown straw hat. 19 year old Merintha Blacker with bamboo fishing pole, Brig Gardner with right hand on fishing pole. 1 ¾ year old Delos Gardner held in left arm of father with face behind mother’s high crown hat. Maria Blacker Gardner in white blouse, dark skirt. 14 year old Fannie Blacker in white dress and bonnet, 9 year old Kemuel Blacker. Grandpa and Grandma Edward and Althera Blacker

Picture taken while visiting the Brooks home in Wyoming around 1906. Will Blacker with shot gun, Ed Wilkes with guitar, his wife, Mary Blacker Wilkes and baby Arvilla on chair. Kneeling front: Mr. Brooks with sheep and dog, Thomas Blacker in hat near door holding 9 month old, Theadore. 2 ½ year old Leroy standing on stool with feet just above sheep’s back Back: Mrs. Brooks in doorway. Hettie Wilkes Blacker at front doorway with high crown straw hat. 19 year old Merintha Blacker with bamboo fishing pole, Brig Gardner with right hand on fishing pole. 1 ¾ year old Delos Gardner held in left arm of father with face behind mother’s high crown hat. Maria Blacker Gardner in white blouse, dark skirt. 14 year old Fannie Blacker in white dress and bonnet, 9 year old Kemuel Blacker. Grandpa and Grandma Edward and Althera Blacker

Edward Blacker holding garden produce, carrots, turnips and possibly red beets, assisted by a grandchild. This picture was taken before his death in Afton, November 27, 1910, a year after his daughter Mary Blacker Wilkes’ death, and six months after his father-in-law, Isaac Loveday’s death.

Edward Blacker holding garden produce, carrots, turnips and possibly red beets, assisted by a grandchild. This picture was taken before his death in Afton, November 27, 1910, a year after his daughter Mary Blacker Wilkes’ death, and six months after his father-in-law, Isaac Loveday’s death.

The Edward Blacker and Althera Loveday farm 1.75 miles north and one mile west

of the intersection 4th Ave and Washington Street in Afton. It is on the southwest

corner of the intersection of Allred Road and Kennington-Burton Lane. The house

was built in about 1912-13. Photo was taken in August 2012.

The Edward Blacker and Althera Loveday farm 1.75 miles north and one mile west

of the intersection 4th Ave and Washington Street in Afton. It is on the southwest

corner of the intersection of Allred Road and Kennington-Burton Lane. The house

was built in about 1912-13. Photo was taken in August 2012.

The Edward Blacker and Althera Loveday farm in August 2012.

The Edward Blacker and Althera Loveday farm in August 2012.

The Edward Blacker and Althera Loveday farm in August 2012.

The Edward Blacker and Althera Loveday farm in August 2012.

The Edward Blacker and Althera Loveday farm in August 2012.

The Edward Blacker and Althera Loveday farm in August 2012.