As a general rule the time comes when fledglings leave their nests. Such a practice is not confined to the bird-family only, but we humans are about as prone. The world is a big place and, oft times, designed moves are made for any number of reasons. Often, necessity designs our moves but, perhaps, more often the moving of one's family does come by choice. Due to the lack of opportunity in one locality, a family looks to another community for better opportunities to provide for the family. Such mobility of families has always been and undoubtedly will remain, for the desire to improve is part of human nature.

The Blacker family of Clutton is but an example. So far as records are concerned, we have found no positive story of just when our direct ancestry moved to Clutton. When records of the average person began to be kept such as, in our case, the church records in Clutton, one or more of our direct family 'showed' up. Seemingly he was already there - but how he got there, or why he went there, or from whence did he come still remains an interesting mystery. True, we have a story from another Blacker family to which we have not definitely proven relationship, that "one day three brothers left Stoke Lane - and Nicholas ends up in Clutton about 1680". There remains a great possibility that if we knew the full details, our family could spring from this same Nicholas. However, all of his children are not listed on any records which we have found, therefore, if we ever have occasion to attach ourselves to him we must find the name of his child who begat an ancestor to us. Our first William could have been one of the brothers Nicholas left in a nearby village and who could later have come to Clutton to share any good fortune that may have come to Nicholas. It very easily could have been our ancestry had nothing to do with the three brothers but, rather, moved into Clutton even generations before and were already there when Nicholas arrived for there was known to have been Blackers in Somerset many, many years before Nicholas of whom we have been referring ever showed up.

The Blacker Monumental Works, 2004

The Blacker Monumental Works, 2004

Could the Nicholas of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire living a hundred years earlier, have brought his bitter disappointments of the practice of primogeniture of which we referred to in an earlier chapter, down into Somersetshire or even into Wiltshire and then to Clutton? There are many possibilities. Were our first known ancestor one of those fortunate 'firstborn' our family story would, in all likelihood, be much less limited, but certainly it would not have been less challenging nor less interesting. The unknown in our research lies still ahead and to someone in the next generation or the next may dig out or, perhaps, even stumble onto a record which will illuminate a new chapter.

We must now return to fact from this fancy of the past few paragraphs. In Clutton, one of the earliest family pursuits was, according to our friend and distant relative, Frederick Blacker, the very business operated by his father, grandfather and great grandfather, who was our direct ancestor. Frederick was now the operator and co-owner of the 'F. Blacker & Son, Monumental Sculptors'.

To again remind the reader, Frederick of Clutton and our Blacker lines converge in our common ancestor Alexander Blacker. Frederick and Great-Grandpa John Blacker were second cousins, therefore, to the generation to which we, the grandchildren of Edward Blacker belong, second cousins three generations removed.

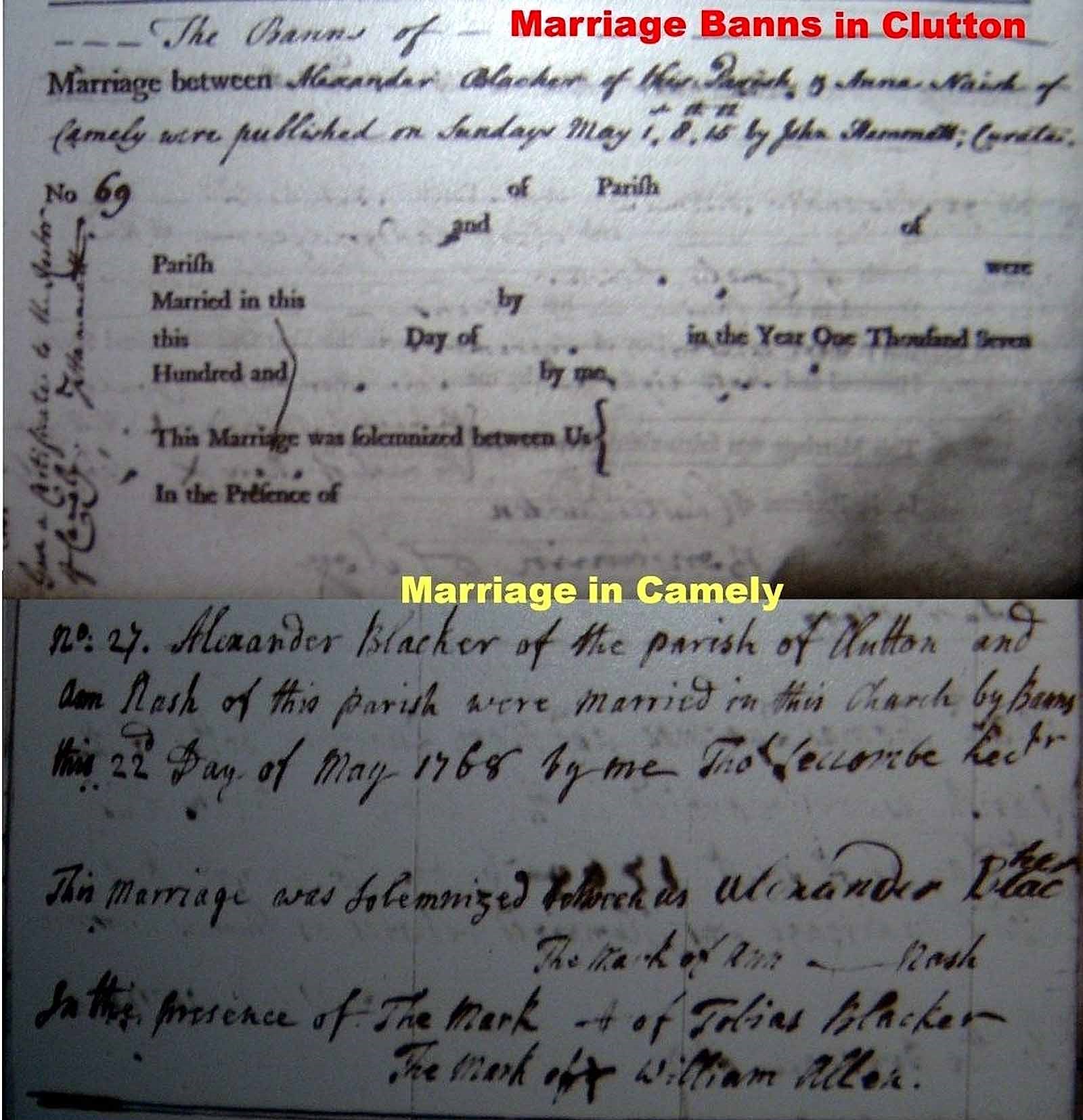

The marriage banns for Alexander Blacker and Ann Naish are shown at the top

of the image. They were read in the Clutton church. The marriage took place

in Cameley as shown on the bottom part of the image. We can see from the marriage

record that Alexander could write but Ann could not because she had to make

an X for her name.

The marriage banns for Alexander Blacker and Ann Naish are shown at the top

of the image. They were read in the Clutton church. The marriage took place

in Cameley as shown on the bottom part of the image. We can see from the marriage

record that Alexander could write but Ann could not because she had to make

an X for her name.

On the official stationery of the Clutton monumental business is printed, 'Established in the year 1716'. If the Blacker family started the business in 1716, it would be interesting to determine which Blacker. We have been advised that our first Tobias, who was christened in 1718 entertained John Wesley about 1739. At that time, he was the monumental sculptor and his house and works were within the Clutton churchyard. This simply means that when Tobias was christened, presumably as a baby, the business was already operating when he was born. Our deduction is that there must have been, at least, one operator ahead of Tobias. In as much as it is a proven fact that the business has been a family industry for the last 266 years, would it not have been quite probably that Tobias predecessor may have been none other than his father, William, born about 1683 and probably a family newcomer to Clutton?

According to Frederick, Tobias' third child but eldest son, Alexander, was the man who became the letter-cutting artist described as being the son who carried on the business following Tobias. Alexander married Ann Naish and they became the parents of 14 childrenDuring these years there were two Alexander Blackers married to two women named Ann. They were having children in the same town at the same time. There is no way to be certain which children belong to which set of parents. , the eldest of which was Tobias, a name-sake for his grandfather, and, again, our direct progenitor.

All the more, with a large family, it seems work would have been provided for Alexander's sons in this stone cutting and polishing business. Help would have been needed in the quarry, the cutting yard, in the polishing or letter cutting room. Tobias was the eldest by ten years of the living sons, so it seems most probably it would have been he who would have inherited the management position of the business. This especially, when we consider that he was but twenty-four years of age and yet single, when his father, Alexander, passed away leaving, so far as our records show, eleven children. The youngest was a baby, being a month less than two years of age. What a challenge this grandmother faced! Alexander died 31 Dec 1792, age 46.

As stated, it is logical and highly probable, that another of our direct ancestors, this time, Tobias, would become supervisor of the Monumental Sculpturing business. He married his wife following the birth of their first born, George, whom he claimed as his own at the time of George's christening. To this union came an additional two daughters, the latter of whom was not born for yet another four months following the early death of her father. Tobias, was but 31 years of age when he passed away. He passed away 26 Sep 1799. Mary Sage Blacker the young widow not yet 26 years of age, was left with George, four and a half years of age, little Ann, not two and Hannah who never saw her father, born 26 Jan 1800. Such situations had been faced before by others and, in all likelihood, situations like it will be met again simply because there is no alternative. Certainly such are not the choices of the survivors.

The pages of history have closed on us as to the daily - and yearly too, problems which confronted Alexander's widow and her remaining children, other than our now deceased Tobias. It would seem their employment problems would have been somewhat assuaged by their closeness to the family business. Their todays had already passed into their yesterdays and some of their pain was being put behind them by Mother Time, but this was not so with our more recent young widow. Her tomorrows had seemingly all dropped in on her todays. For today she had the whole world on her shoulders. It had to have had been frightening. Her widowed mother-in-law, even with her larger family would have had an advantage in that she had become a part of the family business and must have enjoyed a degree to security for her future and her family's future. Her oldest son, Tobias, had taken over the management of the business when his father left. Now that he, Tobias, has also departed, his younger brothers were there to fill in. Next younger son of Alexander's family, George was now twenty and the next son, William, nearing seventeen. Their mother, Ann, was being reinforced and there was a sense of stability evolving as the days passed.

Not so with the young widow, Mary Sage Blacker. She and her little son, George, now four and a half, had been living in Clutton for less than three years. She was but a daughter-in-law to the family. As good to her as her mother-in-law could be, there could not be expected too much help. She was already burdened with about all she could handle. This, in no sense of the word, is intended to diminish the possibility of a Ruth-Naomi or a Naomi-Ruth relationship. Until we learn differently, let's accept that that is what it was with Mary and Ann. After all, Ruth chose to go into the fields to glean, one head of grain, perhaps one kernel at a time, in a very menial, hardworking manner. This did not destroy the Ruth-Naomi relationship. Let us think the relationship in Clutton was similar and they very well could have been, but yet the situation was different.

Mary Sage was from Cameley and our genealogy shows that Cameley had been the home of the Sages for at least two or three generations. We wonder if it were not to there she returned. We don't know, however, we have been told by no less an authority of family matters than Frederick of the more modern day sculpturing firm, that little George was raised by his grandparents. My note to this effect was at a time when I hadn't fully realized that little George's grandfather, Alexander, had already been deceased seven or eight years. Could it have been his grandmother Ann Blacker with her already heavy burden, who made a Ruth-Naomi situation real within her own family? We don't know, for as previously stated, the pages of that history have been closed to us. It is not unthinkable that George's mother, Mary, had parents over in Cameley who would have room for them. Mary, however, was her parents' last child of a family of nine children. Would their age and health and circumstances permit the raising of young George Blacker? We have no answer excepting to skip the years of George's growing up to maturity. Later we find from Clutton parish registers, that he married a young lady from Timsbury to the northeast approximately three miles from Clutton. Remember that Cameley is approximately that distance to the south and west from Clutton. George's wife was named Elizabeth Bowditch, and they were having their children christened in Clutton.

It seems that it was at the point of Tobias' passing away, that the managing of the stone cutting business was transferred from our direct line of ancestry to others of the family. As stated earlier, Alexander had other sons than our direct ancestor, Tobias, and undoubtedly, the lot fell to these sons. Whether son William became involved, we do not know, however, we are aware that this William's son, William Henry, was operating the business in the latter part of the 1800s. This was just prior to the time his son, Frederick took over the reigns of the business in and around the turn of the century into the 1900s. It was this Frederick who became our correspondent during the 1930s and 1940s, and who passed away in 1948. His son Charles and daughter, Freida became the co-owners and were operating the business as late as the 1950s.

The George and Elizabeth Bowditch Blacker family had children who were born during the 1820s and 30s, excepting their eldest son and our direct progenitor, who was born in 1818. They did more than any other of the Blacker family in changing the old family routine of living and dying in and near Clutton. This family, probably due to necessity, literally blew itself apart in quest of a better life.

Apparently the parents, George and Elizabeth, remained in Clutton all their lives. They were both buried in the same grave as his father, his grandfather and his great-grandfather - four generations of menfolk. Note that Elizabeth passed away ten years prior to her husband. George died and was buried in May. In November of the same year their son, William in America, hired the Blacker Monumental Sculptors to cut new letters and repaint letters on the stone.

The George Blacker and Elizabeth Bowditch and children generation, really blew apart the old family tradition that children usually stayed near the 'family nest'. Scanning through what did happen - to Monmouthshire; to the U.S. thence to Nova Scotia and then back to the U.S.; married and ended up in Dublin; off to far off Australia so it has been reported; to the U.S. for both the two younger.

Most of the sons of this generation became "Columbuses" of the Blacker family. Perhaps a family chart with explanations will best describe them.

Click here to see George Blacker and Elizabeth Bowditch Pedegree chart and details about where their children went.There has to be a story, for such a breakaway by a single family in the little town of Clutton must have been quite catastrophic, particularly if the same trend had been repeated in other families of the area. By going to a public library and checking in 'Lyons Topographical Dictionary of England' we will find a brief description of the town of Clutton thusly, "3 1/4 miles S by E from Pensford and on road from Bristol to Wells and Shepton-Mallet. In 1842 it had about 1400 inhabitants, largely coal miners".

We have wondered previously in this story as to what the men folk of our families were doing for a livelihood. Unquestionably some of them were following the work of most Clutton menfolk - and boys too, for youngsters were mustered into wage-earning pursuits as early as they were physically competent to handle a tool or a piece of coal. Child labor laws to protect the helpless children, did not always exist. For centuries, this form of child abuse had to be tolerated by parents, for the economy of the working class families was such as to require all the help possible to assist in putting morsels of food on the table. Our families were still enduring - and did endure for many years yet to come, the hardships of, perhaps, part time work, or work with wages hardly enough to keep body and soul together. Such conditions were found, particularly in Europe in factory or mine or in any other occupation during the seventeenth, the eighteenth and even well through the nineteenth centuries - the very centuries thru which we have been attempting to follow our families.

As seventeenth century colonization started in the western hemisphere and far off Australia, the yearnings of the common peoples of England, were for freedom from the social injustices which had been endured by their forebears. We use England as an example for it was from there our families originated, but the peoples of other countries of Europe, as they also emerged from the long period of serfdom and virtual slavery of the later years of the renaissance, yearned for the same. Stories from over the wide bodies of water which separated England and Australia and which separated the Americas from England, brought hope that with the hard labor to which they already were accustomed, there would surely be opportunities of greater rewards than the few pence their weekly wages now provided.

It was opportunity these people were longing for. As our youngsters sit in their class rooms today they learn of the centuries of struggling for not only economic freedoms but, also, of social freedoms and of religious freedoms. It would seem of the three the basic and of foremost importance to the families of the working classes would have to be the first - economic freedom. The others were of value and became very desirable when the first could be assured. Satisfying the physical needs of every member of the family had to be their goal - not wholly at the expense of the other needs, but it became the concern of the father and the mother as they sat their children down around their tables and placed the little ones in their beds. They were willing to work for it, but they felt their rights to a decent and wholesome living condition. This was for what they longed and deserved.

George's and Elizabeth's eldest son John, now married and in a home of his own already, by 1846 had four little children. Undoubtedly he was a coal miner in Clutton, for he followed that work for much of the rest of his life so far as we are able to tell.

How interesting it would now be had John or Maria, my great-grandparents and others of my generation, written a note to history of the existing conditions of their time and their feelings as they were making the great decision of moving from Clutton. The 'why' for planning such a move would be most interesting to us now. Reason tells us it must have been to better their living standards - but who knows, probably it was with the hope of maintaining what they were accustomed to. If coal mining was the trade they knew and, undoubtedly, that was the situation then, had the Clutton mines run out of coal? These were soft coal mines and probably with manufacturing preferring hard coal, the demand for soft coal diminished to where there was no market for it. Any number of things could have provided reasons for moving. Let us content ourselves by becoming assured that they, themselves felt it to be advisable.

Can we pretend we are looking into their home one evening after John had returned from work? The house, at best, would likely have been but a small cottage- perhaps a garden spot with room for flowers - roses particularly - for this was still more or less a rural area. While the little town itself boasted of better than twelve hundred population twenty years before John's move, at no time could its populace have been considered crowded, as much of England already was at that time.

By this time the cities of England were beginning the use of natural gas for their street lighting, but probably Clutton had never yet enjoyed such night-time luxury. Within the homes by the 1840s, they were beginning to use kerosene, a by-product of coal, which had become plentiful. As they sat around their evening meal the evening before they left, there must have been a certain amount of concern. We don't know, but, could John have made a trip to Abertillery to inquire of the possibilities for work in the mines or had there been correspondence from a friend who had proceeded them? In 1846 or 47 there may have been no newspaper containing classified ads, for it was a little early for newspapers and too, the ability to read, even if newspaper were available would be another question. By the 1840s of which we are dealing ,one out of every three people in England were unable to read or write.

Companies owning mines could have contacted mines which had more help than needed due to diminishing coal which easily could have been a possibility in Clutton. John, unquestionably, had a job prior to their moving, for this would have been too much of a venture to start with a family with no assurance of work ahead. This writer - and perhaps the reader- has had experience in moving his family and it would seem quite natural to credit John and Maria with 'butterflies' in their stomachs the night before.

It is also likely that John had even made arrangements for a house over in Monmouthshire in advance of their moving. This again would be a usual thing, but we don't know. Their plans surely were made as to how they were to make the move. We don't know whether it was by the more modern way of travel or still by horse and cart. The new way was by railroad, for the steam engine was now a limited way for traveling but John and Maria had a problem in getting from Clutton to Monmouthshire. While the total distance would not have been much more than 40 miles yet, if they went anywhere near direct they would have had to cross the Bristol Channel, a finger of the Atlantic Ocean which separates south England from Wales. During this period Monmouthshire was a part of Wales. It was sometime later that Monmouthshire was officially to be considered as a part of England.

The logical place for the moving family to cross the Channel would be at or near Bristol. By 1930, the railroad crossed over to Wales by tunnel from Bristol, but it would not seem that as early as 1846 there would be a tunnel for traffic. Undoubtedly, early ferries would have been relied on, for the distance across the channel from Bristol to Newport is from five to seven miles. Maybe even small boats would be available rather than a ferry. While forty miles does not appear to be a long way, yet under the conditions it would undoubtedly have taken at least two days, providing they took with them their household goods. If they were sufficiently fortunate as to have been able to go without their belongings, the trip could have been made in one long day.

Their little family of four children consisted of Sarah, at the time, seven to eight years of age; next, a namesake of his father, John; the next to the youngest was Elizabeth Ann, two to three years old and lastly, little Margaret probably about a year old.

Whether John was unable to find a home within the city of Abertillery or not we don't know, but it seems the little suburb of Abertillery, probably not more than a mile away, known as Cwmtillery, was to be their home. In family history it has come down to us that their home was Abertillery, however, all subsequent birth records of their children shows Cwmtillery.

Baby producing continued after arriving in Wales, for little daughter, Mary, was born on the 12th of April 1849. Records do not tell us when the little baby died, however, she passed away as a child. A couple years later, Edward was born on the 10th of September 1851. Following in succession were four more children, a boy, George, a girl, Mary to replace the name Mary of her earlier sister, and then a little boy, William. Finally Sarah Ann, their last, who was born in 1863, but not in Monmouthshire, for the family had moved to Mountain Ash in Glamorganshire, where she was born.

Subtracting from the ages of the children born in Cwmtillery to the new baby in Mountain Ash, it can be estimated that John and Maria and family lived in Monmouthshire approximately fifteen to sixteen years. This made John about 45 years of age, still a relatively young man when he moved to Mountain Ash. Undoubtedly, his earlier children married and remained in Abertillery. John was to live another 30 years, all in Mountain Ash where both he and his wife, Maria were buried in 1893 and 1890 respectively.

- Sarah (2 August 1839, Paulton) = Edward Bishop

- John (15 December 1841, Clutton) = Margaret Allen

- Elizabeth (8 March 1844, Clutton) = William Smith

- Margaret (23 July 1846, Clutton) = George Blacker (cousin)

- Mary (12 April 1849, Cwmtillery-died as a child)

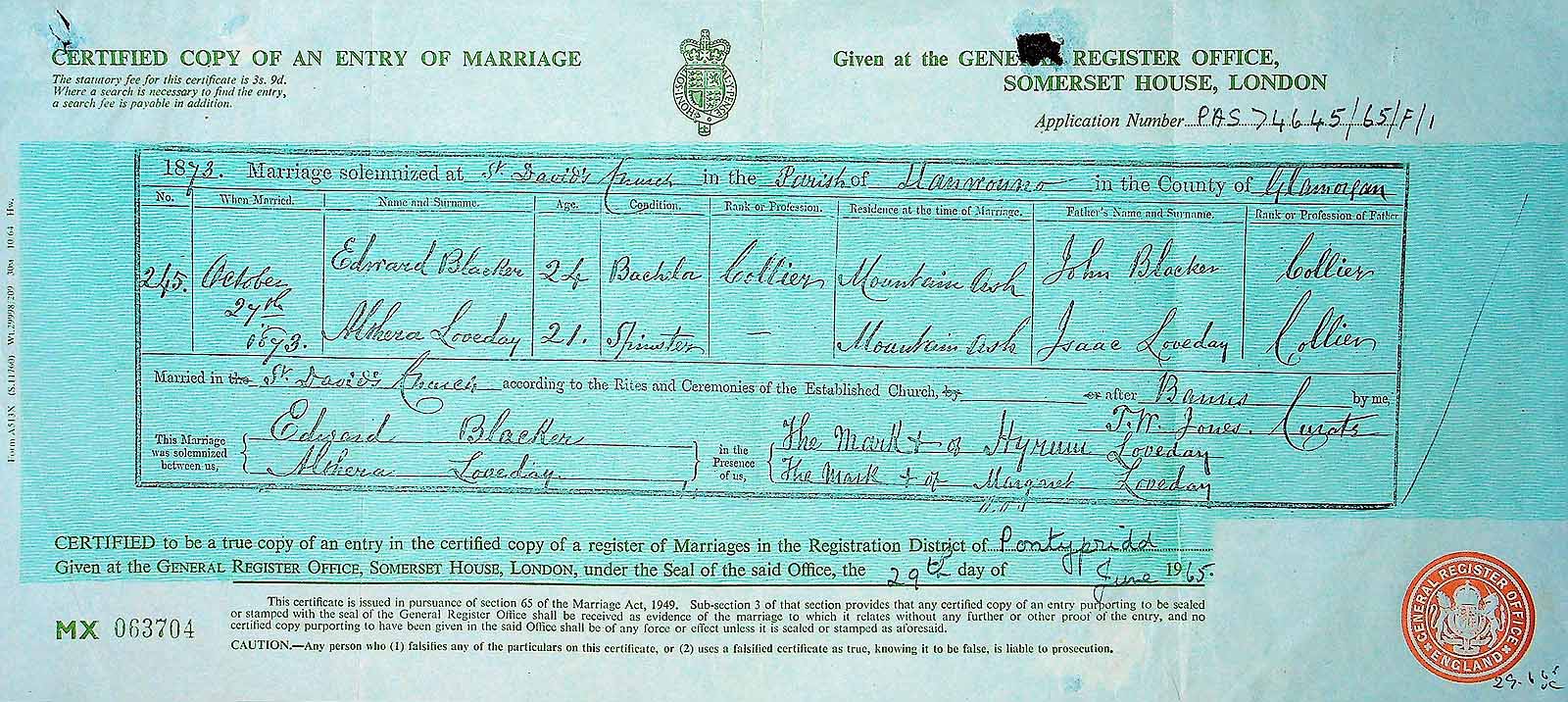

- Edward (10 September 1851, Cwmtillery) = Althera Loveday

- George (abt 1853, Cwmtillery-died about age 20 years)

- Mary (3 Jan 1857, Cwmtillery) = William Watkins (abt 1853, Mountain Ash)

- William (28 April 1859, Cwmtillery) = Sarah Passmore & Louisa Smith

- Sarah Ann (31 December 1863, Mountain Ash) = David Gethin [moved to Ohio]

It should have been noted two paragraphs back that Edward's birth record according to family records was 15 June 1850. However, on the 18th of July of 1944, a certified copy of his birth certificate was made at the General Register Office, Somerset House, London. It shows his birth date as having been 10 September 1851 in Cwmtillery, which date was certified by the informant from the (X) The mark of John Blacker, Father, Cwmtillery on the 20th day of October 1851. Family records often see the need for further documentation and while birth, marriage and death certificates are not fool-proof from possible error ,they are accepted usually as preferable to family records. In making up a permanent family record it seems quite logical to use, in such a case as this, the date given by the birth certificate, but to make a notation elsewhere, perhaps in 'Necessary Explanations' the family date for future consideration. A generation later, the Edward Blacker family had a similar situation which will be mentioned later, in which the place of birth was different than the family record showed, as well as the birth date. Such errors are not unusual.

Birth certificate for Edward Blacker.

Birth certificate for Edward Blacker.

Let us refer back to John and family arriving in Mountain Ash before the birth of their second Mary. First, let it be suggested that the reader may appreciate more the family background, if he be a member of the Edward Blacker family organization, by scanning a map of Wales and, perhaps, reviewing to a degree, the story of Wales. Space will not here be taken for that purpose for, after all, brother John of the brothers and sisters of the family to whom we are presently referring, was the only one of the family who moved to Wales. As the account will later give, the majority of the brothers, in particular, left the United Kingdom for their greener pastures. Interestingly, it appears that dissatisfaction with their homeland fell to the boys of the family with one exception. We have no indication that either of the two girls were successful in convincing their husbands to leave the shores of the British Isles, excepting Mary, who joined her husband in Dublin.

Five additional children had come to the home of John and Maria since their arrival in Cwmtillery, Monmouthshire, during the probably 15 years which followed their leaving Clutton. Again it becomes interesting to speculate the reason for moving. Coal fields were abundant in Wales - Monmouthshire originally belong to Wales but "for purposes of administration, been accounted within England", so history tells us. Mountain Ash was a smaller town than was Abertillery and undoubtedly had opportunities of which John could benefit. As the crow flies across country, the two towns are twelve to fifteen miles apart, however, with the country being quite mountainous, the distance by road is longer. Despite the short distance, even today one can go only part way by rail with the balance by bus.

At this point let me divert to personal experience, and intermittently refer to Great-grandfather, John and family. As stated earlier ,I had the great opportunity of visiting in Mountain Ash. At 1:15 of the afternoon of Wednesday, February 26th 1930, I boarded a bus in Cardiff for the town of Mountain Ash. I was alone, but not overly concerned for I had been in northern Ireland one year and in the midlands of England for the second year of my mission, and the train and bus systems were not altogether new to me.

While it was still late winter with cool, but not cold temperatures, the country side was green. The leaves on the trees of the varieties which shed their leaves in the fall had not yet come out but, nevertheless, there was considerable green foliage on the hillsides as well as green grass. The British Isles remain pretty much green the year round, due to quite continuous rainfall - at least frequent rainfall, especially during the winter season.

By three p.m. or thereabouts, the road sign indicated our approach to Mountain Ash. It has now been nearly fifty two years to the month since that trip, and my memory is not providing me with all the little details. I was aware I had relatives in Mountain Ash, for my father had so written me. Dad's cousin, Ted, of Evanston had written letters to the folk prior to his coming to America and I had met him in the summer of 1927, as indicated earlier in this story. However, he had lived in Cwmtillery, Abertillery which address did me no good, for I was miles from there.

After getting off the bus I started making inquiries for anyone by the name of Blacker and, seemingly, it wasn't as well known as I had hoped. I was directed to a Blacker residence on Victoria St., but the man at the door claimed he was not the one I was looking for nor did he know of him. I could see the cemetery across and down the hill from where the town itself is located. I walked across the bridge over the railroad track and sauntered over to the cemetery and spent a few minutes feeling sure I had to have some relatives underground there but, I didn't find a tombstone with the Blacker name. After spending probably fifteen minutes meandering around in that area, I concluded that I had better be getting on with my business of finding living relatives instead. I had more confidence that they would be able to help me than those in the cemetery. I returned back across the bridge to the town proper and inquired of a policeman. Policemen had always been a Mormon missionary's friend. From him I was directed to follow up the road along the hillside with houses more distinctive than the smaller houses down town. Eventually I reached the right house which was some distance out of Mountain Ash proper, into a residential area known as Penrhiwceiber. I was dressed as most missionaries dressed during those years, with my black coat and its black velvet collar, and black trousers with a white pin stripe. I was, of course, carrying my suit case.

What Uncle William thought when he opened the door after my using the big knocker on his heavy outside door, I don't know. He was then in age a few years younger than I am at this writing, but I imagine, had I been in his place at the time, thought the visitor could have been none other than a salesman with his case of products to be peddled. I didn't give him time to follow through with such possible thoughts. He had no idea that a relative from American was to visit them, and when I told him who I was, he reached out his hand and grasped me by the right hand and pulled me into his arms. It was the first time he had seen any of this brother Edward's family since Edward left Wales for America about fifty years before. Catching them rather unawares didn't seem to make any difference. There certainly was no evidence that I was not welcome, but to the contrary, it was not long before others of the family of other households knew I was there. After visiting for a short time I met Uncle William's wife, Aunt Louisa (his second wife) and their sons, Ernest, about twelve years of age and Harold, probably twenty five to thirty years of age, but yet single and living home, returned home from work following my arrival. Uncle William told me to bring my bag and he would show me my room. They had a reasonably large two storied brick home as most homes in England are, and the whole house was nicely furnished with comfortable furniture. The bedroom I was ushered into was of medium size and nicely furnished. Uncle William said it was a room not being used by the family at that time. Within an hour or an hour and a half after I met them, Uncle William suggested that we walk back to Mountain Ash so as to meet his sister, Aunt Mary Blacker Watkins, also, of course a sister to Grandpa Edward Blacker. It was a disappointment that she was not at home at the time, however, her married daughter, Edith Dart lived in a nearby house and we visited with her for a few minutes.

I failed to mention that Cousin Harold had joined Uncle William and me on this trip back to Mountain Ash and the three of us spent, perhaps an hour, walking on the hillside streets of Mountain Ash. Several points of interest were pointed out to me, such as the home where Grandpa and Grandma (Edward and Althera) had lived and where their first three children were born namely, Uncle George, Aunt Sarah Ann and Aunt Mary. The family then moved to the Ferndale area over the mountain some ten miles, where my father (Thomas) was born. I was shown a neat little home called 'Rose Cottage' which was built by Uncle William's father, John Blacker ,of whom we have already started writing about. This was a nice, but plain stone house. We passed the little place where Grandpa and Grandma Blacker (Edward) were married on the 27th of October 1873. The little building in which they were married was next to the large stone church - St. David's Church - of the Church of England.

As we walked down to the main street, Uncle William pointed out a large somewhat square stone building across the railroad tracks, which appeared to be what we would call a city building. In all probability, his father, John of whom we are dealing, held a position in the city such as a city councilman or alderman, or some other office. He lived in this building "61 years ago." This would have been back in about 1869, which would have been six or seven years following their arrival in Mountain Ash. Uncle William himself, had retired from the mines where he had been employed most of his life and where, for the last several years of his service he was what he called the 'manager' of the mine. His father, John, in his turn, had been a high official in the mine - as I recall the position was "superintendent." Of this I am not sure, but it was an important position. Cousin Harold, at the time, was a weighmaster, one who weighed the coal as it came out of the mine.

In a letter from Frederick Blacker of Clutton, which was dated 27th of October 1940, he stated that Charles Moody of Clutton, who was a nephew of our John Blacker of Mountain Ash, had said that at one time his Uncle John was keeping the Miskin Inn at Mountain Ash. Uncle William told me this on one occasion also.

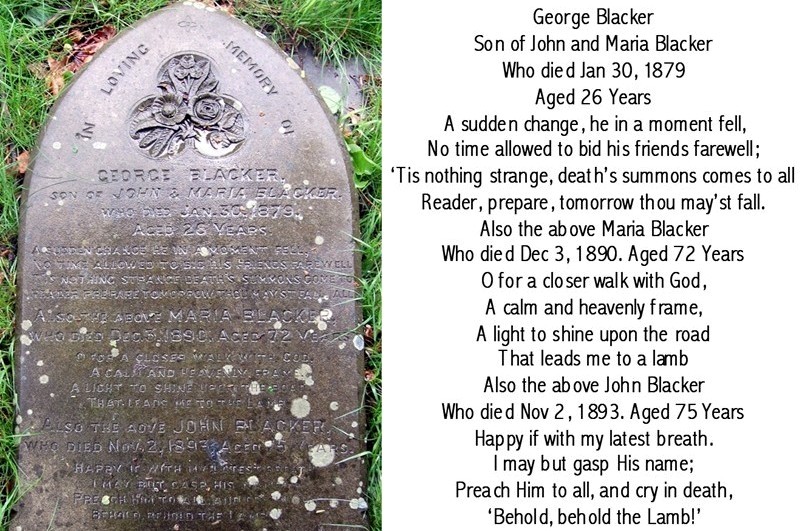

Ruth Blacker Waite and her grandaughter Mariah Waite in the Mountain Ash Aberffrwd Cemetery next to the tombstone of John, Maria and George Blacker

Ruth Blacker Waite and her grandaughter Mariah Waite in the Mountain Ash Aberffrwd Cemetery next to the tombstone of John, Maria and George Blacker

That evening, following our return to the home that was named 'Rosemount' on Vaughan Terrace - the official address - Uncle William got the old family Bible and I copied considerable family data. He showed me a photo his brother, Edward, had sent them of his, family which was taken in Illinois, which included Edward and Althera and five of their children - the baby, Maria, having been born after they left Wales. Fifty years later, I saw for the first time since the viewing it in Uncle William's home, a copy of the same picture, when my cousin, Allie Gardner Hyde, showed it to us in Afton, Wyoming in the home of her brother Delos. From Allie's picture we later secured copies.

Also, at Uncle William's, he showed me some family heirlooms among which was an old chair which was claimed to have been in the family four hundred years. Now, as I write this account, how I wish I could turn the calendar back over these last fifty-two years since this visit, and inquire more thoroughly than I did at the time. Hopefully, the reader will not criticize me too harshly, not as hard as I do myself, for at that time I did not fully appreciate the significance of family antiquity of heirlooms, nor historic data pertaining to the family. Were I to have the same opportunity today, I am sure there would be many more questions asked rather than just listening with amazement as I did at the time. Uncle William also showed me a walking stick belonging to his father with his initials ,"J.B.' neatly carved, with the year "1852" neatly engraved, also. Uncle William also had a watch which he showed me - a pocket watch - which he bought from his brother, Edward - my grandfather - before he left for America. Could there have been a story relative to this sale; a story of concern on Edward's part as to whether he was well enough financed for the trip?

As the evening came on we visited and Uncle William recalled that before the Edward Blacker family left Mountain Ash, he visited the Isaac Loveday home on occasion, when Mormon meetings were held in the Loveday home.

The next morning, Thursday February 27th, Uncle William and I took a bus which passed by their door, and we went to the Mountain Ash cemetery, where I got some information from the tombstones of Uncle William's father and mother, John Blacker and Maria Gould. She had died on 3 December 1890, at the age of sixty-nine. He died 2 November 1893, both in Mountain Ash, where, of course, they were buried as is evidenced by the tombstones. Also buried in that cemetery, is Thomas Loveday, son of Isaac and Sarah Danks Loveday and a brother of Grandma Althera Loveday Blacker (Edward). He died as a twenty year old young man.

Tombstone of George, Maria and John Blacker in the Mountain Ash Aberffrwd Cemetery

Tombstone of George, Maria and John Blacker in the Mountain Ash Aberffrwd Cemetery

From the cemetery, Uncle William and I walked over to Aunt Mary's home which was not far away.. Aunt Mary, at that time was 73 years of age and was two years older than Uncle William. Both were in good health. From there, we walked some little distance to another relative, this time to see Esther Blacker Harvey, a niece of Uncle William. Interestingly, Esther was the daughter of Uncle William's sister, Margaret who married her cousin, George Blacker.

In the evening back at Uncle William's home, Aunt Mary and her daughter, Edith Darte and small daughter, Eunice, called. We spent the evening visiting and I took a couple flash pictures.

At Uncle William's home in Wales in 1930. He and his sister Aunt Mary are seated together in the front.

At Uncle William's home in Wales in 1930. He and his sister Aunt Mary are seated together in the front.

The next morning, Friday, February 28tth Uncle William and I took the train and then a bus to Abertillery in Monmouthshire. This was the old home of John and Maria that they had moved to when they left Clutton and before they moved to Mountain Ash. Several of the family still lived in Abertillery and Cwmtillery, a suburb. After arriving, we called at the home of an Edward Blacker, a son of Aunt Margaret. He accompanied us to the home of his sister, Rosetta and her family. She had married a Mr. Morris. Living with them was their daughter Rachel, who advised me that she had been corresponding with my cousin, Delos Garner of Afton, Wyoming, and also, with another cousin, Irene Nisbet of Rupert, Idaho. Rachel had married and her married surname was now Evans.

From the Morris home, we walked to Aunt Margaret's home - both she and her husband had been dead for a few years, but their daughter and family was living there. We then returned back to cousin Rosetta's and had a nice dinner.

Uncle William, Cousin Ted (Edward) and I went up to a cemetery Blaina Gwent and got a little tomb stone information. From there we walked to another cousin's, Tilitha Blacker Woodward, another daughter of Aunt Margaret. She, along with her other children, had two adult young daughters, both of whom were deaf and dumb. I don't remember whether or not they were twins. Their names were Mildred and Monica. They had a younger sister Doris, called Dot, who was ill that particular day, and two younger boys, Bernard and Victor.

Uncle William Blacker and Aunt Mary Watkins at her home in Mountain Ash, Wales, March 1930.

Uncle William Blacker and Aunt Mary Watkins at her home in Mountain Ash, Wales, March 1930.

From there we went by bus to Blaina Cemetery at Blaina, a small suburb of Abertillery. We picked up a little cemetery information of deceased members of the family. From here we returned to cousin Tilitha's and had tea. She had asked that we return from the cemetery visit. From here we again returned to cousin Rosetta's, where we visited for a short time while awaiting for the bus to depart for Mountain Ash. Cousin Ted seemingly was not married and was unemployed, for some of the men from the mines were out of work. Times were hard during these years.

It may be well for me to clarify: William Edwin Blacker of Abertillery and later of Evanston, Wyoming, was known by the family as Ted Blacker. He was the son of Uncle William of whom I have been writing. Also in Abertillery, and who had accompanied Uncle William and me to visit his sisters and others, was the young man who was named Edward Blacker, a son of Aunt Margaret and Uncle George Blacker. He was also known as Ted. I have not heard of him since he saw us to the bus in Abertillery and regrettably, to my knowledge, there has not been any correspondence from Cwmtillery nor Abertillery.

We arrived back in Mountain Ash - actually Penrhiwceiber - at 8:45 p.m. Aunt Mary and Cousin Edith Darte and husband dropped in for an hour or so of visiting.

Saturday, March 1st Uncle William and I walked over to the coal mines, or collieries, as they called them, where all of the Blackers, including Grandpa Edward Blacker worked before they left for Ferndale area, prior to their leaving for America. Later in the day, Cousin Harold and I took the bus and traveled to Aberdare,, another town about five miles to the north and west from Mountain Ash. There were no relatives here, but we looked around and did a little shopping. Here Harold insisted on buying the book, 'The Life of Christ' by Faraar, which he noticed me taking an interest in while he was doing his other shopping. This book I still have in my possession fifty-two years later.

That evening all of us at Uncle William's house went over to Aunt Mary's home in Mountain Ash. At this visit, I met another of Aunt Mary's daughters, Mary Jane and her husband, surname Hayes, as I remember the name of Bill. Daughter, Edith Darte and husband were also there. We returned to Uncle William's by 11 p.m.

Clutton parish church with churchyard where our ancestors were buried as it appeared in 1930.

Clutton parish church with churchyard where our ancestors were buried as it appeared in 1930.

No L.D.S. meetings were being held in the area, for I had been told no missionaries were laboring there, and there were no branches of the church there at that time. Uncle William and family had not planned to go to their church, the Methodist, in Mountain Ash, so Sunday March 2 (1930) was just another day.

Harold and I went for a reasonably lengthy walk up on the mountain in the direction of Ferndale - an area, where my father, Thomas, was born. The distance was too far away to go all the way - so we returned after about an hour. In the afternoon, Uncle William and I went over to Cousin Esther's home She was Aunt Margaret's daughter. We also visited Esther's daughter and husband, he being a policeman, who were there at the time.

After our evening tea, Aunt Mary, her daughter, Edith and husband and baby, and, also, Cousin May and husband with their children came over and an enjoyable evening was spent visiting. This was to be my last evening, so when the visitors went home it was a farewell. I realized there was little likelihood we would ever be together again. After just a few days visiting with kin folk it is surprising how close we become. I was to correspond a few times with some, but even that so infrequent that it came to a complete stop after but a year or two. I think were I to do it all over again I could do better than I did. There has been one lesson I have learned through the years and that is that people are people, relatives are relatives, friends are friends even though oceans and continents separate us.

Monday morning, March 3rd, 1930, I took the bus just in front of Uncle William's home and left for Cardiff, where I took the train for Bristol across the channel - that at 10:30 a.m. As mentioned earlier, the railway has an undersurface channel or tunnel from Cardiff to the Bristol side which took possibly ten minutes for the train to travel. This, undoubtedly, was a shorter and an improved route that great-grandfather, John Blacker, took when he moved to Monmouthshire back in the late 1840s.

After arriving in Bristol, it was necessary for me to wait an hour before a train left for Clutton, a town of my ancestry. The account of this short trip of perhaps thirty minutes has already been related commencing at the beginning of chapter two of this account. While I made some contact with these distant relatives at that time, my correspondence with Frederick (not at home at time of my visit) brought to me a great deal more family information than I obtained on the visit. However, something which could never have been gotten by correspondence, was the fact that on my visit I walked the very streets where my ancestors and their families, for several generations, had walked before me. I saw the very surroundings, the buildings, their own homes and the very church house they frequented. I visited the cemetery or churchyard, as the English spoke of it, in which their tears had been shed as they lay one after another, after another of their loved ones to rest. This hour spent there perhaps brought a union of spirit with our ancestry which is obtainable in no other way. It was an experience of a lifetime and one I shall forever cherish.