Janice F. Demille

Color Country Spectrum, Wednesday, June 30, 1976

The Blakes

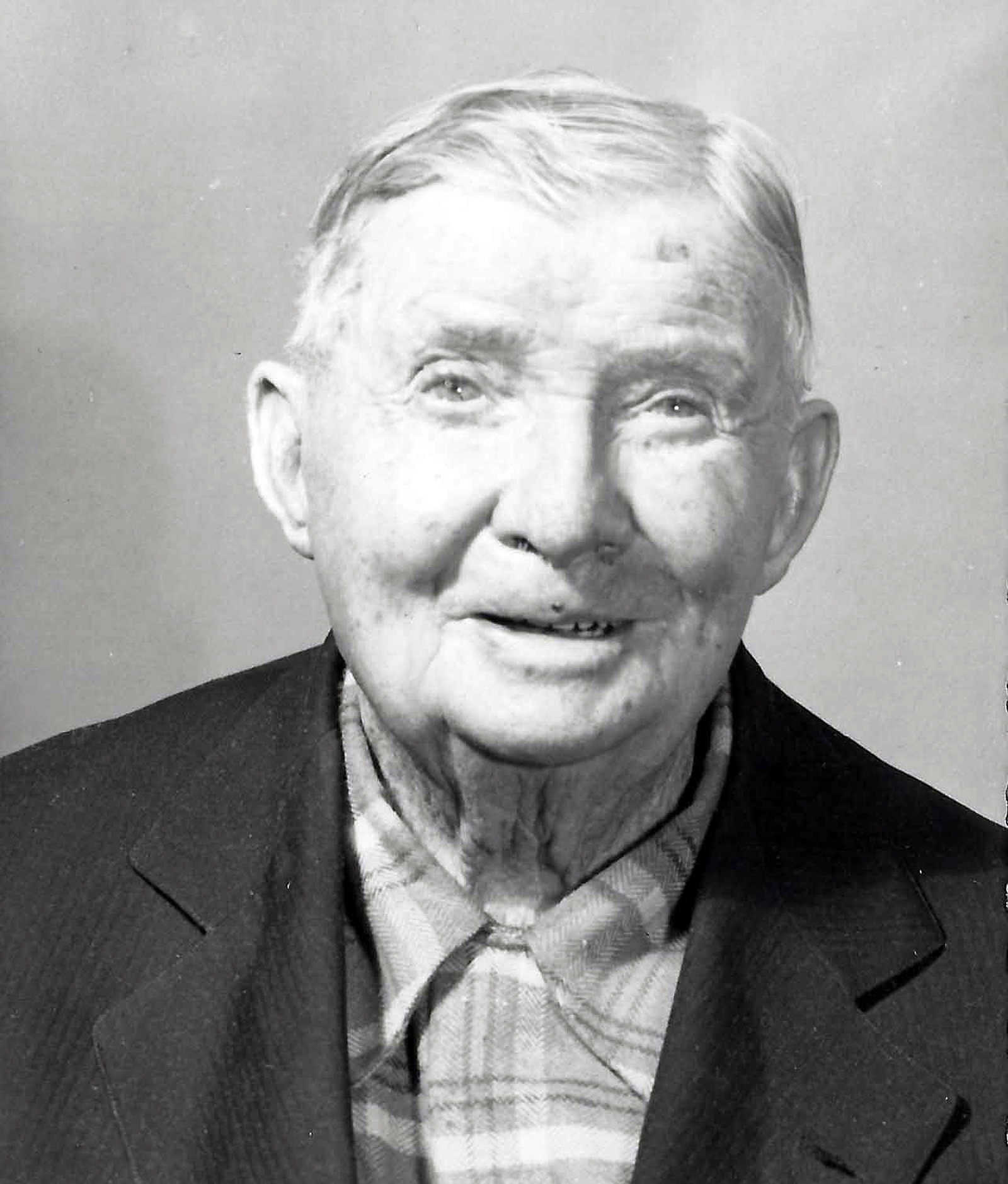

Isadore Larson Blake

Isadore Larson Blake

Around the turn of the century, there were quite a few homes being built in Bloomington, although the first house had been built there in 1879. When a house was built, everybody in the town turned up to help. It was not a money-making project, but rather a chance for neighbors to work together' with each other.

Isadore's youngest sister, Zelda Larson, who now lives in St. George, Utah, remembers when Wally and' Isadore's home was built in 1908. Zelda was an inquisitive youngster of seven who made a point of visiting them often, which was not hard to do because she lived just a half a block away. She remembers how proud they all were because, for that day, it was really a nice house.

The old church building across the river at Price City was torn down and the rock used to build this house. Dode Worthen, who did many rock houses in Southern Utah, laid up the rockwork. A true work of art, the black rock foundation was eighteen inches thick and those walls still stand to, tell their story of pioneer mastery. It only cost ten dollars to shingle the house. Brig Carpenter did, the carpentry work in' it, including the designs over the doorframes and mantle piece. The rest of the building was a family and community effort.

Bloomington had its only little branch of the Mormon Church, but leaders from near-by St. George went out to visit and supervise about once a month. When Bishop James McArthur, Andrew Windsor and George Whitehead went to visit, they took a wagonload of boys and girls of their own. The children loved to go because the Bloomington families always had a big chicken dinner for them. It was a special day for the entire town.

Tithing was paid in produce. When the folks at Bloomington took their butter, eggs, wheat, corn or whatever else they harvested to St. George, they took one-tenth to the old tithing house. (The building later became the Quality Bakery; Lynne Clark's Photo Studio now stands there.) Little money was to be found by these good saints, but they faithfully paid the Lord's tenth of what they had.

The two important things to these people, their families and their church--would have been hard to separate. The church to them was not something apart from life. It was life.

Wally and Isadore lived on the homestead, working hard, rearing their family. Knowing the joys and trials of pioneer life. Finally they traded the homestead for James S. Jones' home in St: George.

The Joneses

For the next several years Joneses lived in the little rock house, and, farmed the surrounding land. One of the Jones girls, now Le Fave Leany, remembers the many parties all the people in town had. Once a group of boys went to the Apex mine (the famous copper mine about fifteen miles west of Bloomington) after some snow. No ice was available in the entire area, but with the snow they could freeze homemade ice cream. A group of girls made the ice cream 'mix and tire boys froze it in an old-fashioned ice cream freezer. When they opened the freezer and began to eat the ice cream, it was salty and inedible. They decided the snow must have been salty, but were certainly disappointed after air of that hard work.

Chester Jones planted fig trees and the family must have looked forward to their delicious yield. But before the trees had produced, James and Alice traded the place for a dry farm at Mt Trumbull, Arizona. Once again, this Bloomington homestead had new owners.

The McCains

These were religious people who came at last to live on the old homestead. They were hardworking, courageous people who had helped settle communities in three states. And finally Albert and Rhoda McCain arrived in Bloomington, where they settled in the little rock home Blakes had homesteaded. They found a peaceful settlement where they learned to know and love their neighbors, the Carpenters and, the two Larson families who lived there. The thick walls of black rock helped keep their home warm in the winter and cool in the summer. A long screen porch which Joneses had built on along the east end of the house' was a favorite meeting place for all the grandchildren during hot summer days.

Rhoda Elizabeth Chamberlain

Rhoda Elizabeth Chamberlain

Albert Alexander McCain

Albert Alexander McCain

During those years the old homestead rang with laughter. Two grandsons, Robert and Arthur Cromwell, grew up there and went to school. Later a granddaughter, Very Snyder, joined them. The three children rode one horse to school in St. George, sometimes taking turns and occasionally all three riding together. In the summertime from one to two dozen grandchildren joyously went to live with their grandma and grandpa. Beds were no problem. They slept on the floors, or preferably, out under the pomegranate bushes with a quilt and a pillow. Much of the time it was too hot for even a sheet over them and nothing stopped them from simply stretching out on the grass after a long day of work and play.

Parks or playgrounds were unknown; the" grandchildren played along the ditches, in the hay fields and around the corrals. Up on the hill above the ditch were acres of open space. Nothing grew; there was no water, But it was a children's paradise. There was an old, crumbled down house with no roof which the grandchildren loved to play around and chase the squirrels that lived there.

Marie Iverson Waite, a granddaughter who now lives in Homedale, Idaho, wrote, "There were a lot of wild burros and donkeys roaming the country down along the river. Many times, Robert, Arthur and some of the neighbor boys and sometimes we girls would go down on horses and round up some of them. We would drive them home to a corral. The boys would then have a great time riding them. They would sometimes dare us into trying it. After everyone had been bucked off several times, the burros would be turned loose to rest up for our next wild west show.

"We had many a race across the river on horses, most of us riding horseback. There was one old horse that usually laid down in the water when we crossed it. Whoever was on him could plan on a good ducking. But we, as well as the horse, enjoyed it.

Food and Farming

The fig trees planted by the Joneses now yielded a lovely crop for hungry grandchildren and adults alike. There were also many fruit trees. During her younger years, Rhoda had helped right in the fields, doing a man's work hauling hay and performing other farm labors at Moapa Valley, Nevada, and Mt. Trumbull, Arizona. But after they moved to Bloomington, she did not get out into the fields so much. She had her own garden and plants around the house and she irrigated and took care of the lot. Her lovely garden was fenced in and there she grew the usual vegetables, as well as some unusual items. She grew vine peaches, a small, round fruit about the size of a peach which grew on a vine like a cucumber. They turned yellow when ripe and made delicious preserves. Rhoda also grew okra, herbs and watermelons. She always had sales at Mathis Market in St. George for her garden produce as well as eggs and the butter and cheese she made. There was a special demand for the tender asparagus shoots she grew which reached one and a half inches thick. In addition to selling her wares in St. George, she also sold to neighbors, usually being paid in other goods or grain for her chickens.

Due in part to their garden, the McCains were almost self-sustaining. They had their own milk, butter, eggs and meat in addition to their fruit and vegetables. During the harvest, they canned their own vegetables and fruit for the winter ahead; they also dried much of their fruit. They did buy sugar and salt and a few other little items.

Rhoda had an incubator and would sometimes hatch out as many as one hundred little chicks at a time. She also put eggs under any chickens that wanted to set. They raised several pigs every year, giving them enough pork to last all year round. Albert cured the hams and bacon. They ground the rest of the meat into sausage, then stuffed it into little cloth bags or little sacks. Sometimes she cleaned the entrails out and stuffed sausage into them.

They also made their own head cheese and liver hash. To make head cheese she scraped everything she could get out of the head, ears, tongue and feet of the animal. After thorough cleaning, she cooked it and pressed it into nice blocks or rounds of headcheese. To eat, it was sliced off and used like cold luncheon meats now. (Have you ever read the list of ingredients in some of the canned meats on grocery shelves now days? At least the pioneers knew theirs was clean.)

A few steps from the kitchen door, down under the old granary, was Rhoda's cellar. There were shelves lined all around with goods, including bottled fruits and vegetables, a variety of raw vegetables and produce, and. pans of cold milk. She had no refrigerator to keep lhe milk or butter cold, but put the milk in round, flat milk pans and' put them in one special shelf. Here it was protected by a screen door, which kept out flies. When the cream had risen to the top of the milk, it was skimmed off and made into delicious, rich butter, which she churned regularly.

Flies were a constant problem during the summer. Rhoda kept a fly swatter in the house and when she was not doing something else, she had her fly swatter busy. She absolutely did not, like flies in her house, so whenever anyone came in the door, they would try to shoo the flies away and then dash in and shut the door as quickly as possible.

This was a busy life for Rhoda, growing her garden, making her butter and- cheese, preserving food for winter's use, making lye and soap, and feeding the varying number of family members living with them. Life here kept Albert busy too. But they were used to hard work; they had known nothing else, and life here was actually easier than it had been at Mt. Trumbull.

Albert had to haul all of their culinary water from St. George, a task, which, had to be done about twice a week. He built a heavy stand in front of their gate between two large cottonwood trees. On this platform were kept the two large barrels of water. When the water got low, he put the barrels on the wagon and took them to town where he filled them from a tap. When he returned from town, the barrels were unloaded onto the platform, which was the same height as the bed of the wagon. Then they used a short rubber hose to draw the water out by the bucketful as it was needed.

Their trips to town were made on the days they needed water. Albert and sometimes Rhoda would get the mail, market Rhoda's produce, and do other errands. Rhoda sometimes went to Will Whitehead's home in St. George where she spent the rest of the day ironing for them. These daylong trips seemed especially long in the heat of the summer.

The grandchildren went along every chance they had, feeling important to be, riding with their grandpa, even though he delighted in teasing them about the Yahoos, which he claimed, lived up in the rock cliffs along the way. Half-believing the Yahoos did live there they wouldn't have been too surprised at any sort of monster which may have appeared. Counting on their grandpa for protection they were a captive audience for his stories. Albert was known by his grandchildren as fun-loving and witty. He enjoyed teasing them at every opportunity; making up opportunities was his specialty.

Albert, with Robert and Arthur helping him, kept busy farming. He always had a saddle horse or two. Along with raising their own hay, grain, sugar cane and corn, he even grew broom corn. Alfred Carpenter, who lived next door, had a broom corn shop. Albert worked with him in the broom corn which was grown in the surrounding fields. Albert went out into the fields where it was growing, helped harvest it, and then helped make it into brooms there in the shop. People were allowed to turn in their old broom handles toward the purchase of a new broom. The men sanded the handles, painted them; and made them into " new" brooms.

Once Alfred's wife Elsie needed a new broom, so she sent one of her children up to the shop after one. They sent her a broom with a refinished handle, This was not at all satisfactory as far as Elsie was concerned and the broom was returned with the message that she did not want a broom with a slivery handle.

As mentioned previously, the old homestead was situated along the banks of the Virgin River. The river was necessary for the very existence of the settlement; the land could not be farmed without it. But as in all of the pioneer settlements along its banks, the Virgin took its treacherous toll from time to time. Every time a big flood came down, it would take an acre or two of Albert's alfalfa field with it. It kept cutting away through the years until there was hardly an alfalfa field left.

McCain's youngest daughter, Leoma Iverson, lived across the river where they were renting a little house which was built up on stilts so the river could not reach it. One day some of the family were going to Leoma's . The water was so high, that Rhoda decided she would have to ride the horse too. She said she would rather walk any day than ride a horse. Nevertheless, she got on this horse, sitting side-saddle even though she was actually on a conventional saddle. The water came up so high that she had to hold her feet out in front of her to keep from getting wet. When she got to dry ground, she immediately got off, saying that this was the hardest day's work in a long time. She never did like to ride horses; she could work hard in the fields, but would rather walk the five miles to town than ride a horse.

The LDS Church continued to provide the McCains with satisfaction and a feeling of belonging. They were active in the little branch in Bloomington, with Albert acting as Presiding Elder for some time. They were simple people; they made no show nor pretense for the world. Perhaps people who are so genuine have no need for acclaim. They were not wealthy in the eyes of the world, but wealth they did not need. Through hard work, patience and day-by-day faith in God, they met the challenges of each day. Their friends respected them; their family love them. Who is to say that they did not have wealth?

Here on the old homestead, and later in St. George where they moved, they spent their last years surrounded by loved ones who honored them

And what of the Old Homestead?

The Homestead in 1976

The Homestead in 1976

Forsaken. All alone as the sun fades behind the distant horizon. The passer-by sees you only as a broken-down old house with crumbling chimney, thick, rough walls and weeds growing rampant. Now weeds and thorns thrive. You've always borne weeds, but they were carefully pulled from among the flowers and garden back when: The frail, never over ninety pounds-in-her life grandmother nurtured her flowers raised chickens and pigs and worked right with the grandfather in the fields, hoeing weeds, irrigating planting and harvesting.

The dozens of grandchildren playing along the ditch banks and in the ditches, climbing the gnarled cottonwood trees, walking the fences and playing with their grandfather at evening kept you young. You must have smiled at their games of make-believe; you must have sweated with your family as everybody pitched in to dig the Johnson grass roots from the melon patch; you must have wept in disappointment when the frost came too early and rejoiced with them when the harvest was gathered. And they shared with you the wonder as flood waters of the Virgin rose higher and higher then watched in horror as the raging currents cut away acres of your fertile land.

No more is taffy pulled within your walls. No longer does every evening find the grandfather reading from the family Bible, then kneeling around the big, rough-hewn kitchen table with his family in prayer. These things have passed, but not the memories. The great-grandchildren marvel and laugh to hear their mothers tell of visiting Grandma, of getting stuck in the mud, of summers filled with childish laughter and stories of Yahoos, and of having to leave the haystacks to help in the garden or herd the cows.

And some day I shall take my children as my mother took me to their great-great grandparents old homestead to play tag among the fig bushes, to peek into the granary and harness shed, to wonder how anyone ever dared go down into the spider filled fruit and root cellar. Then, as we lie in sleeping bags on your salt grass lawn and gaze at the stars, I will tell my children your stories as I have heard them.

The house after 1976

The house after 1976

The southeast corner

The southeast corner

The west side showing the granary above the cellar

The west side showing the granary above the cellar

The tree east of the house where the outhouse stood

The tree east of the house where the outhouse stood

For years the old homestead was thus deserted, visited only on rare occasions. But over the last seven years, new life has sprouted around it. Purchased by Terracor, the area has been subdivided and developed. It is now a thriving resort center, which has been called the Palm Springs of Utah, attracting visitors from near and afar. Three thousand acres of home sites have been plotted and sold new homes are being built every day.

Up on the bench where children ran and played and nothing would grow for lack of water, a lush green golf course and country club now provide year-round entertainment. Just twenty feet from the old broom corn shop now stands a new fire and police station, Where the youth raced and rode wild burros, now elite riding stables and an arena provide their own form of entertainment: Albert's fields are covered with beautiful new homes and condominiums. Amid this oasis, still standing under the pink, cliffs, the old homestead is truly a landmark from another day.

The future of the old homestead lies in the hands of its present owners. They plan to restore it to its original beauty, furnish it with antiques and thus preserve a portion of the colorful history of Bloomington and Southern Utah.